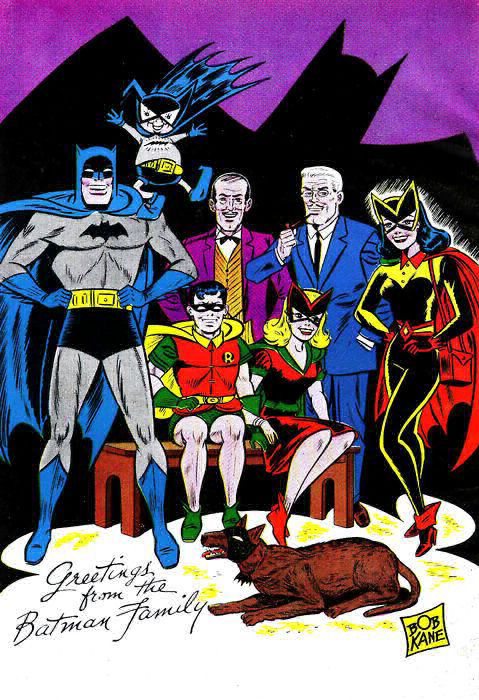

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Robin became only one part (although still the most important part) of a Batman Family.

Bruce and Dick acquired a butler named Alfred in 1943 who integrated well into the tales. But in 1956, they were joined by Batwoman, a well-intentioned heroine who caused trouble because according to Batman - and his writers - crime-fighting was no job for a woman. Batwoman's niece, the original Bat-Girl, was added in 1961 as a semi-love interest for Robin. But it didn’t stop there.

The Batman Family included Ace the Bat-Hound in 1955 (yes, a crime fighting dog that wore a mask), Bat-Mite (1959 debut) a magical imp and Batman's self-declared Number One Fan from the Fifth dimension and even briefly in 1958 Mogo, the Bat-Ape. Yes, an ape in a Batman costume.

Robin Hood scholar Stephen Knight once referred to Richard Greene, the Robin Hood of the 1955 TV series as "everyone's favourite uncle" and as de facto patriarch to a lot of kooky characters, Batman filled a similar role at the time.

As 1964 began, Batman and Detective Comics sales had dwindled. Back in the 1940s, Batman and Robin prospered because their stories were some of the best on the market. That wasn't the case any longer. Editor Julius Schwartz had successfully revamped previously cancelled superheroes the Flash (in 1956) and Green Lantern (1959) bringing them up to date with modern readers expectations and kicked off an era known as the Silver Age of Comics. Readers enjoyed the Schwartz-edited books, including the new team book the Justice League of America (Superman and Batman were only supporting characters in the JLA comic as their editors didn't want to share their characters.)

There was also new competition from rival publisher Marvel Comics, which began to introduce popular characters such as the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man and the Avengers in the 1960s. The Marvel heroes were a little more relatable than the DC superheroes – they had personal demons to conquer, not just super-foes.

And if readers wanted sci-fi whimsy potently mixed with melancholy, there were the Superman comics. As a "strange visitor from another planet" and someone who was "rocketed to Earth from the doomed planet Krypton", Superman was a better fit for the science fiction milieu. Like Batman, Superman had a personal tragedy in his backstory – but that tragedy, the destruction of his home world, was rooted in science fiction.

Batman and Robin's outer space, extra-dimensional and time-travel adventures were far removed from their origins as the victims of street crime and protection rackets.

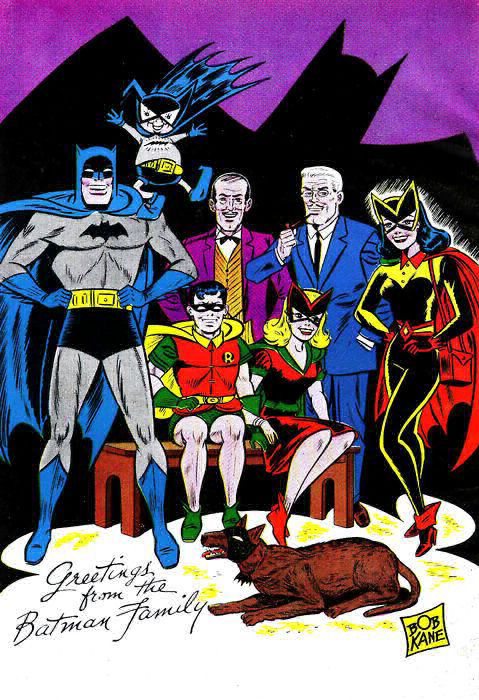

Batman #126, March 1964

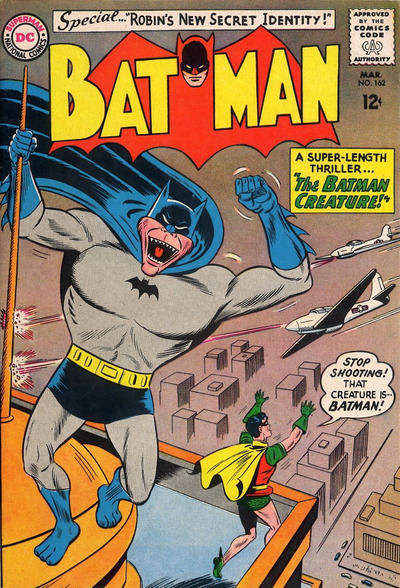

Detective Comics #326, April 1964

Robin had to contend with a Batman turned into a King Kong-sized "Creature Batman" in Batman #162 (cover dated March 1964). In Detective Comics #326 (cover dated April 1964), Batman and Robin were the prisoners of an interplanetary zoo. DC's owners had had enough. Either the sales of Batman and Detective Comics had to improve, or the caped crusaders would be cancelled.

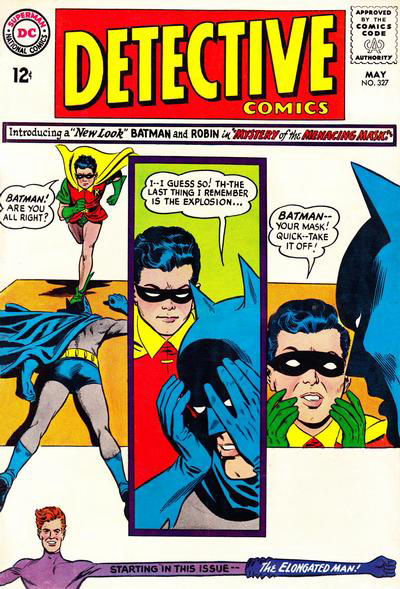

Logically DC turned to editor Julius Schwartz who had success in reviving cancelled heroes. He brought with him writers Gardner Fox (who had guest-scripted a few of Batman's earliest adventures) and John Broome and also superstar artist Carmine Infantino from his work on the Flash. Infantino's artwork on Detective Comics #327 (May 1964) was the first time the Batman feature had not been credited to Bob Kane (even though many other artists had provided the art before under Kane's name).

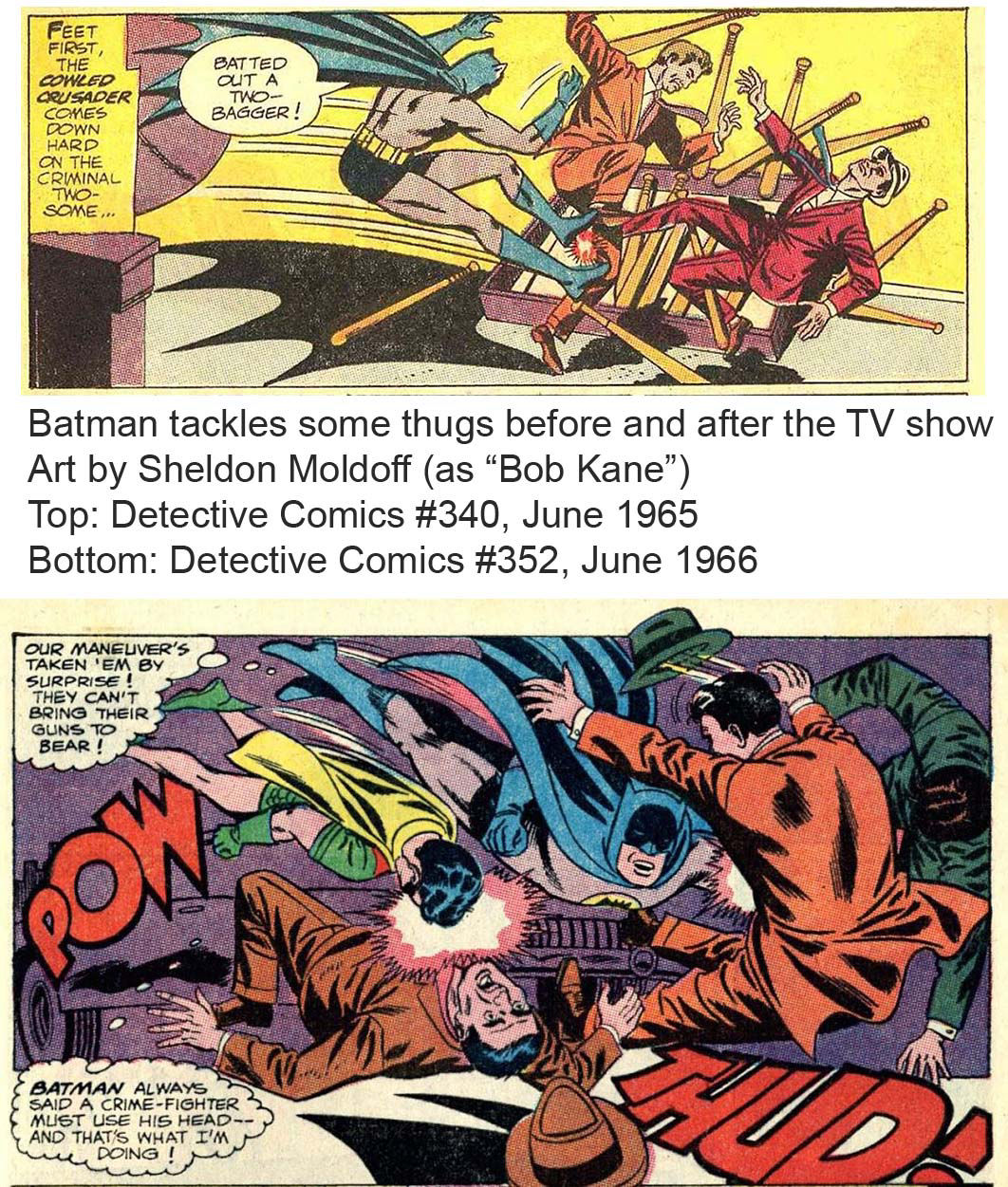

Even the artwork of "Bob Kane" (a part still being played by ghost artist Sheldon Moldoff) changed slightly in the issues not drawn by Infantino.

Infantino also updated Robin's look, drawing him as older than previously depicted. As Infantino explained to Jim Amash in Carmine Infantino: Penciler, Publisher, Provocateur:

I did that purposely, because you can't have a teenaged kid like that fighting crime. He oughta be at least 15, 16. Twelve-year old kids -- that's not Robin. He's got to think like a grown-up.

Robin would grow up even more before the decade was out.

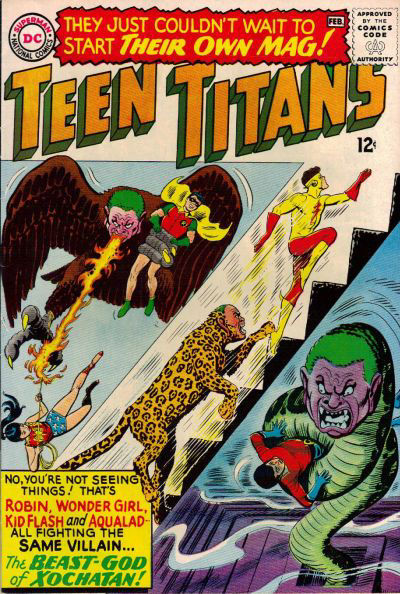

Besides Infantino's New Look, one thing that firmly cemented Robin as a teenager was his appearances in a super-team. Robin, Kid Flash and Aqualad first teamed up in The Brave and the Bold #54 (June 1964). The story dealt with the generation gap between teenagers and adults. When the three young heroes returned in a follow-up try-out (and with the addition of Wonder Girl) in The Brave and the Bold #60 the following year, the cover called the team "The Teen Titans". Teen Titans #1 had a cover-date of January 1966.

Batman and Robin may have fought fantastic menaces with their new families in the Justice League and the Teen Titans, but things had changed in Batman and Detective Comics. Editor Julius Schwartz banished the Batman family. Gone were Batwoman, Bat-Girl, Bat Hound and Bat-Mite -- just unmentionable for years to come.

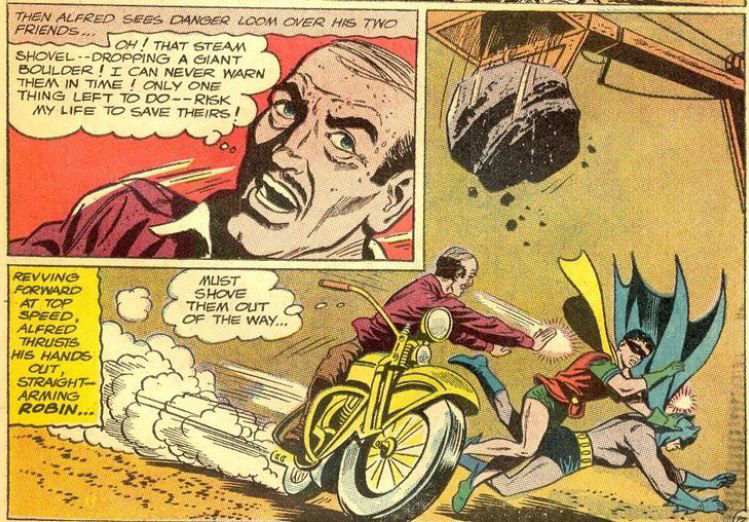

But Alfred, Batman’s butler since 1943, had a more dramatic exit. Batman’s co-creator Bill Finger returned to script Detective Comics #328 (the second New Look issue of Detective Comics), where Alfred sacrifices his own life to push Batman and Robin out of the way of a falling boulder. Bruce Wayne sets up the Alfred Memorial Foundation in his honour, which would play a role in future stories. (The writers hadn’t yet come up with the last name Pennyworth for the character.)

Editor Julius Schwartz explains in his autobiography Man of Two Worlds that Alfred was killed so that he could be replaced by a new female character, Dick Grayson’s Aunt Harriet, who would take over the housekeeping duties at Wayne Manor. Unlike Alfred, she didn’t know the boys’ secret identities.

Schwartz maintained that he introduced Aunt Harriet to quell concerns raised by Dr. Frederic Wertham’s 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent which had characterized Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson’s relationship as the “wish dream of two homosexuals living together”, with only an :”aged butler” for company. Schwartz thought it best to eliminate one of the three men at Wayne Manor. As others have pointed out, the new set-up had Bruce and Dick concealing the truth about their identities from an aged aunt – which to at least some readers made the characters seem more gay, not less.

Schwartz didn’t only change costumes and characters, he changed the type of stories too. Science fiction was more restrained, but was still present. In the first New Look story (Detective Comics #327) a crook uses "radioactive phosphorous" to freeze Batman and Robin in their tracks.

Old supervillains such as the Joker and the Penguin returned to bedevil the Dynamic Duo. The Riddler who had only made two appearances in the 1940s was brought out of retirement in Batman #171 (May 1965). That issue caught the attention of TV producer William Dozier when he decided to make TV stars out of Batman and Robin.

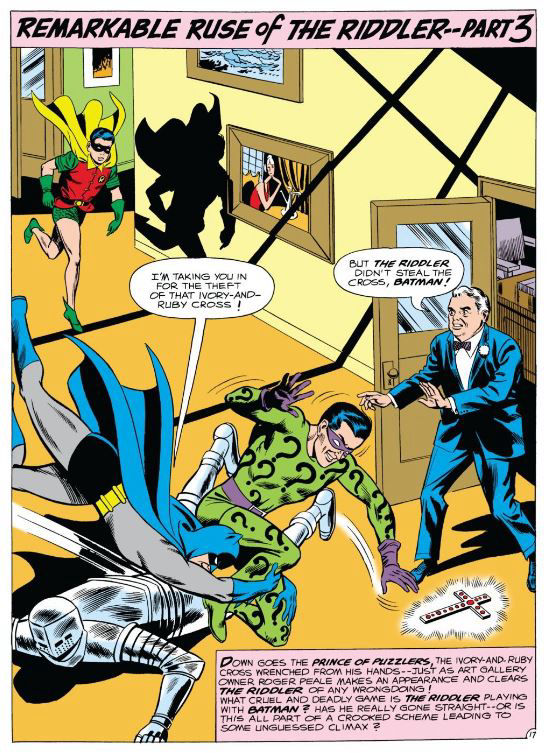

Batman tackles Riddler in Batman #171, part of the Riddler's trick

Adam West's Batman, Burt Ward's Robin and Frank Gorshin's Riddler in the same scene from the first episode of the 1966 Batman TV series

In a sense, the Batman TV series was 23 years in the making. Batman and Robin had first appeared in a 15-part movie serial back in 1943. Movie serials were like television before home television became common. They were weekly serialized adventure stories – running around 15 – 20 minutes – that would play alongside the movies, newsreels and cartoons. Back then, moviegoers didn’t just see one film but a complete entertainment package. These instalments would end on cliffhangers and audiences would need to come back each week to learn how our heroes would get out of trouble. The Batman serial was not one of the best of the genre, although it did lead to a sequel in 1949.

But that original 1943 serial would resurface in 1965, edited together as An Evening with Batman and Robin – a 250-minute presentation. The serial’s earnest but out-dated 1940s World War II patriotism was now marketed as “high-camp”, and it was a big hit with college students. The executives of the ABC television network took notice and took inspiration from the unintentional humour of the original to create a high-camp TV series that would appear to earnest children and delight more-knowing adult audiences with its absurdities.

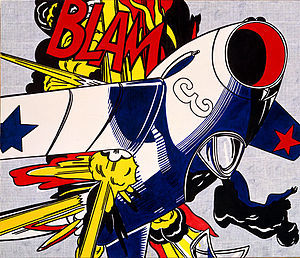

The first episode of Batman premiered on January 12, 966. And for a time, it captivated America with its pop art sensibilities. Roy Lichtenstein’s adaptations of comic book panels from other, uncredited, artists were a big hit in the art world.

The show was the brainchild of producer William Dozier, whose voice could be heard each week as the pompous narrator – an aspect borrowed and exaggerated from the original 1943 serial. Originally, the show was broadcast in half hour instalments on Wednesdays and Thursdays. The Wednesday episode would end with a cliffhanger ending, just like the movie serial. The first episode ends with Robin in the clutches of The Riddler by guest-actor Frank Gorshin. (Gorshin was the first of many celebrity villains on the show, and he’d win an Emmy award for these appearances. The second season opened with a less-lauded guest villain, Art Carney as the Robin Hood-themed Archer.) As the narrator Dozier asked audiences “Will Robin escape? Can Batman find him in time?” The narration would end with a plea to tune it tomorrow – later episodes adding the memorable phrase “Same Bat-Time, Same Bat-Channel”.

Adam West played Batman, and he maximized the show's comic potential while acting as the straight man. Burt Ward was 19 years old when he auditioned for Dick Grayson/Robin -- a somewhat older high school student as in the "New Look" comics. Ward played the Boy Wonder with a youthful exuberance. Ward’s Robin would say “gee whiz” or “gosh yes” whenever West’s Batman would pass on some fatherly advice.

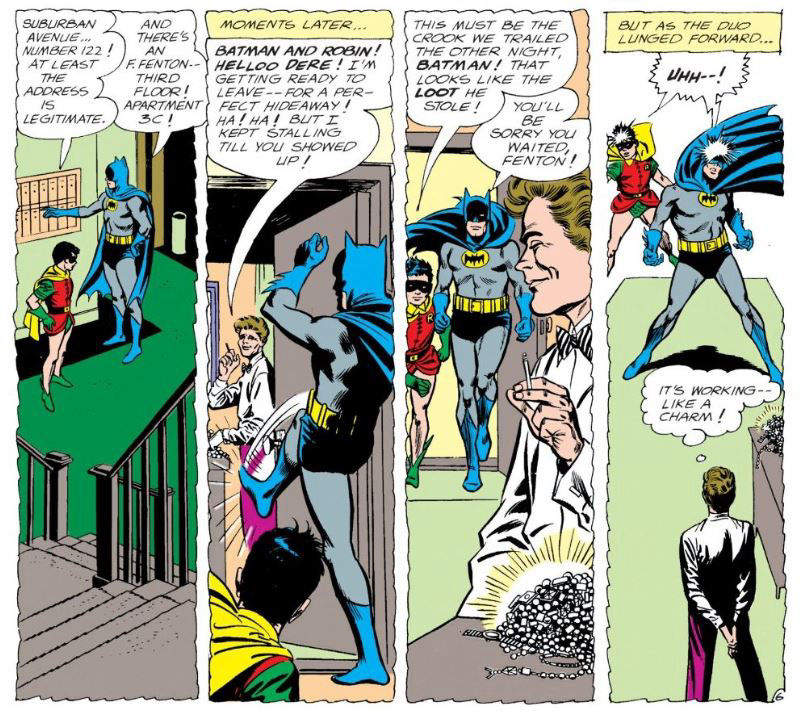

The first episode “Hi Diddle Riddle” was written by Lorenzo Semple Jr. but part of the story was adapted from “The Remarkable Ruse of the Riddler” in Batman #171 by writer Gardner Fox and “Bob Kane” (in reality ghost artist Sheldon Moldoff). Both the comic book and the TV show have Batman tricked into attacking the Riddler, thinking the crook was robbing the owner of the Peale Art Gallery at gunpoint, taking a valuable cross. Actually, the cross belonged to the Riddler. And the gun was merely a fancy cigarette lighter.

The Riddler had previously left them a clue about this – one that Batman figures out in the comic book but that Robin solves in the TV episode.

ROBIN: Holy ashtray! He did tip us off! “There were three men in a boat with four cigarettes and no matches. How’d they manage to smoke?” They threw one cigarette overboard and made the boat a cigarette lighter.

MR. PEALE: You saw him giving me a light as I handed back his cross.

BATMAN: Out-riddled!

That was the second time in the episode that Robin began a unique expression with “Holy”. Earlier Bruce Wayne invited Dick Grayson to go fishing, and when the young man guessed that was just the cover-story for some crime-fighting action he exclaimed “Holy barracuda!” Comic book characters would often have bizarre kid-friendly exclamations like “Holy cow!” or “Holy moley!” or “Holy cats!” to express surprise or excitement. But the camp TV series took the gag much further – coming up with multiple new and very specific “holy” expressions for Robin each week such as “Holy contributing-to-the-delinquency-of-minors!” and “Holy understatement, Batman!.” This catchphrase became the trait that people most closely associate with Robin the Boy Wonder.

Blam! (1962) by Roy Lichtenstein

Inspired by the comic book art of Russ Heath

"Bam!" An on-screen sound effect in "Smack in The Middle"

Jan. 13, 1966 episode of Batman

When the show’s popularity waned leading to cancellation in its third season, the staff at DC Comics were sick of the TV show’s camp sensibilities, but that didn’t stop them trying to make a buck when the Batman TV series was at the height of its popularity.

For a brief, not-so-shining moment, the comics took their lead from the TV show.

The two-part premiere episodes “Hi Diddle Riddle” and “Smack in the Middle” feature a discotheque named “Way to Go-Go”, where Batman meets the Riddler’s moll Molly. In the second episode, Molly disguises herself as Robin and is taken to the Batcave. When she accidentally falls to her death in the Batcave’s nuclear reactor, Batman quips “What a terrible way to go-go.”

Apparently the editors at DC Comics believed that go-go dancing was a vital part of Batman’s TV success.

The cover of Detective Comics #348 (dated February 1966, but on sale on December 23, 1965) featured a checkerboard design at the top of the cover. DC called these “go-go checks”. With the cover-dated issues for March 1966 (the first issues available after the Batman TV series premiered) these go-go checks were on the covers of all DC Comics. (The go-go checks would remain until the covers dated August 1967, by which time Batmania had cooled as had the sales of DC Comics.)

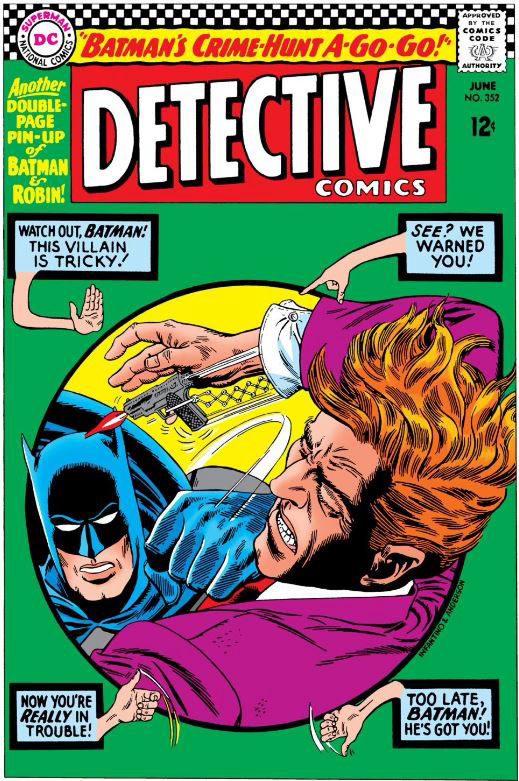

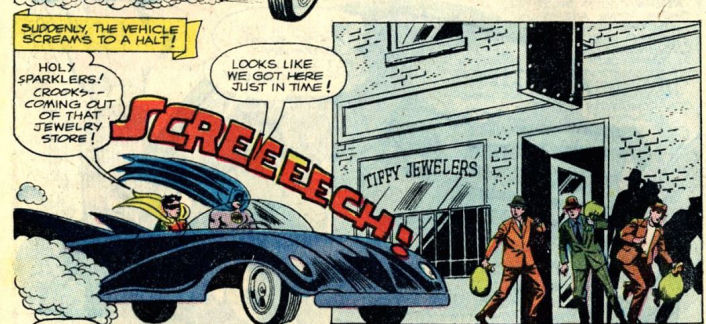

But it was Detective Comics #352 (June 1966) when the influence of the TV show hit with a bang -- and a pow and a sock too. The cover gave the story’s title as Batman’s Crime-Hunt A-Go-Go, and as in the TV episodes, Batman does visit a night-club, although not quite as swinging as the one on television.

The TV show was also reflected in prominence of the sound effects Every punch was accompanied by a sound effect in giant letters. A year before Batman could attack bad guys with nary a sound, effects were often reserved for louder sounds, such as screeching tires. But in 1966, punches were accompanied by the same sound effects you’d see on TV.

Comics are generally a non-naturalistic medium – constructed from static but sequential images and the written word. The tropes that seem perfectly normal – and which serve an actual function – in a silent and purely visual medium like comics seem absurd when applied to a more naturalistic medium like television. To get the same effect in comics, they needed to heighten the tropes so they now serve no function exception to mock the convention of the comics. This was most evident in Detective Comics #357 (Nov. 1966). The title page ("splash page" as comic book fans call them) inserts the TV show sound effects into the opening narration captions. "And how -- and why -- did Batman and Robin track him there? Strange are the singular steps that explain this *pow* meeting!”

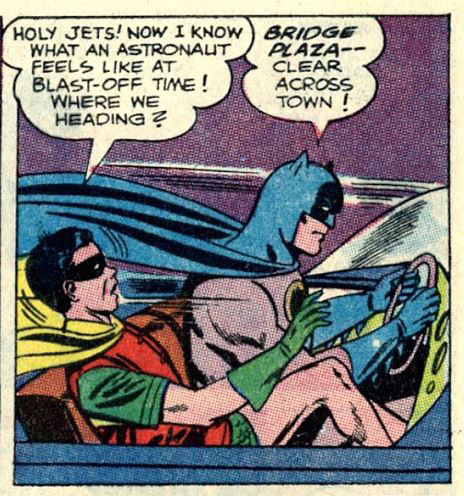

The comics copied something else from the TV show.. In Detective Comics #352, Robin exclaims both “Holy Sparklers!” and “Holy Jets!”.Similar holy-isms would appear in other issues, sometimes with three different Holy expressions appearing on the same page.

"Holy sparklers!"

from Detective Comics #352

"Holy Jets!"

from Detective Comics #352

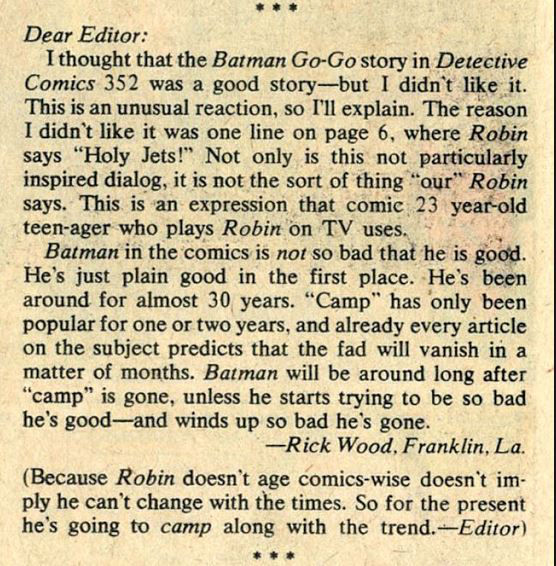

Fans noticed what was happening, and some of them weren’t happy about it. Detective Comics #356 features a letter from Rick Wood from Franklin, LA which calls out the use of the phrase “Holy Jets!” as not being something that “our Robin” – that is to say the Robin of the comic books – would say. He also points out that the camp of the TV show is a passing fad. The editor responds that Robin’s “going to go camp along with the trend.”

Alfred Returns

Detective Comics #356

Batgirl Debuts

Detective Comics #359

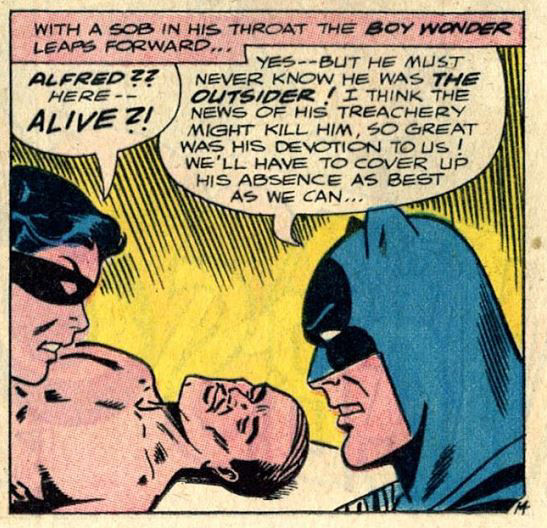

Detective Comics #356's main feature, “The Inside Story of the Outsider”, fulfilled a request from producer William Dozier to restore Alfred to life as the fateful butler would have a prominent role in the TV show. Schwartz says in his autobiography that Dozier was influenced by some early Batman comics with Alfred, but I wonder if it’s William Austin’s memorably comic turn in the 1943 movie serial that inspired his TV appearances, just as the 1965 re-issue of the serial had inspired the TV series. Whatever the case comic book fans can be grateful that the TV series helped restore this popular character.

It turned out that Alfred was only mostly dead and that a scientist had been able to restore him to life, although the process had turned the butler into an evil, monstrous super-villain. Restored to his true self, Alfred returned to Wayne Manor. And the Alfred Memorial Foundation was renamed the Wayne Foundation, the same name used on the TV show.

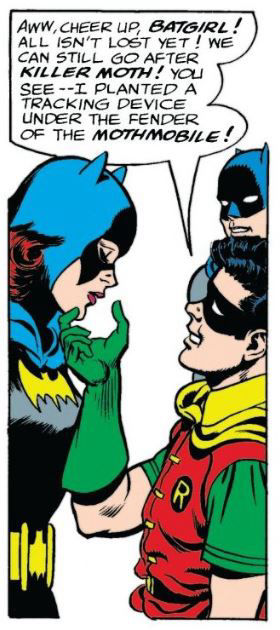

Producer Bill Dozier had another request for DC Comics, to introduce a new female superhero – Batgirl. This wouldn’t be Batwoman’s niece Bat-Girl from earlier in the decade. This new Batgirl introduced by writer Gardner Fox and artists Carmine Infantino and Sid Greene in Detective Comics #359 (cover date January 1967) is Barbara Gordon, the daughter of Gotham City’s police commissioner. As she first appeared, Barbara Gordon is a librarian – a college graduate at a time when Robin was still in high school, but later stories would romantically pair the younger heroes. Yvonne Craig joined the cast of the TV show as Batgirl for the show’s third and final season beginning in the fall of 1967.

When the TV show ended in 1968 the comics floundered. The camp direction was now a detriment. The comic book creators decided to significantly shake up the status quo -- and the Robin the Boy Wonder would change greatly.

But before we move on from the era of the 1960s Batman TV show, I'd like to take a closer look at two episodes that feature the Robin Hood-like villain the Archer. You can find that review in the next section.

NEXT:

PART 6 - Batman and Robin Meet the Archer (1966 TV episodes)

PART 7 - Robin Leaves the Nest (1969 - 1975)

PART 8 - The Dynamite Duo and Goodbye, Hudson University (1975 - 1980)

PART 9 - Robin No More: The Birth of Nightwing (1980 - 1984)

PART 10 - Reboots and Retcons (1984 - Present)

PREVIOUSLY:

PART 1 - The Golden Age of Comics and the Development of the Kid Sidekick

PART 2 -What's In A Name? Robin and Robin Hood

PART 3 - Early Adventures (including Robin's origin)

PART 4 - Batman and Robin meet Robin Hood in The Rescue of Robin Hood (Detective Comics #116)

Contact Us