Throughout their history, comic books have been called junk literature, printed on cheap paper, intended for children, and thought to be a corrupter of morals. Likewise, the Robin Hood stories were once considered a threat to morality, have thrived in populist media such as black-letter ballads and film, are staples of children's literature and according to Stephen Knight have not produced a defining work in a highly-regarded medium such as the novel. The old expression that "the tales of Robin Hood are good enough for fools" is similar to how people now use the phrase "comic book" to mean something silly.

Many Robin Hood comics were published in the 1980s and 1990s -- the time of Robin of Sherwood and Robin Hood -- Prince of Thieves. It was also an important time for the comic book medium as a whole. Genre comic books such as Watchmen, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Swamp Thing gained mainstream attention and acceptance for tackling important political issues of the Reagan-Thatcher years such as the growing disparity between the rich and poor, the increased focus on violent street crime, political corruption and the ever-present threat of mutually-assured destruction. Newspapers often ran articles on comics with headlines such as "Pow! Zap! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore."

I recalled those old headlines with great amusement when this paper was originally scheduled to appear in a session called "Robin Hood and Young People's Literature." After protests by the participants, the title was changed to less-assured "Is this Young People's Literature?" The new title raised a good question.

Once upon a time, comics were mostly for children. In fact, there were rules in place to make them that way. However, comics from the late 1970s to now have lost their youthful audiences. The rules that kept comic books as strictly children's literature have been lifted. The Robin Hood comics – and comics in general – of this era are now more violent than comics of the past. However, increased violence does not mean that Robin Hood comics have truly grown-up.

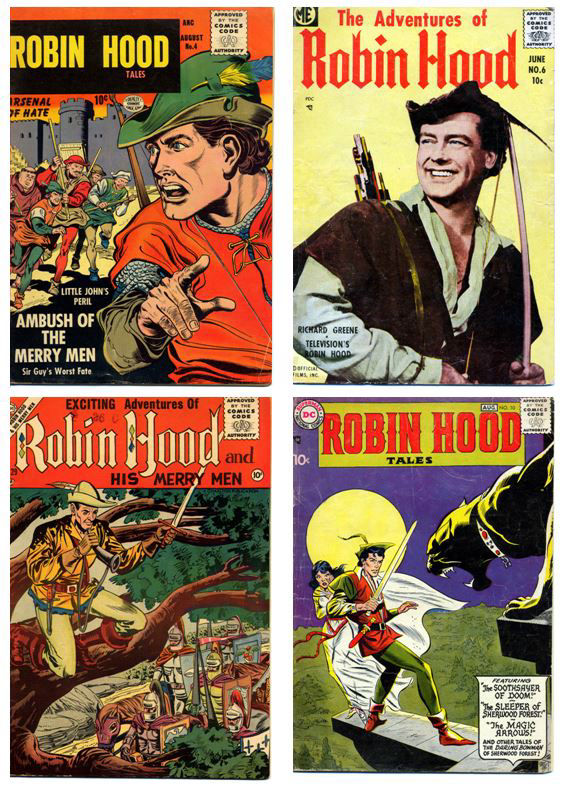

In 1950s, the Robin Hood legend was widely featured in comics. Usually the comic book Robin Hood was clean-shaven and short-haired, like Richards Greene and Todd. This was not a coincidence. Several American publishers capitalized on the popularity of the Richard Greene TV series The Adventures of Robin Hood by producing Robin Hood comics. It was an odd time for an outlaw hero.

Comic book publishers had just voluntarily subscribed to a Comics Code Authority. The code was introduced in late 1954 in response to the Senate investigations, news articles and church boycotts that had linked comic books to juvenile delinquency. It killed the then-popular -- and controversial -- horror and crime comics. Television tie-ins filled the void.<1>

The Code was designed to enforce law, order and good moral values. The first provision was "Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals." The third provision required that "Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority." The fourth declared "If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity." Other provisions prohibited excessive violence, attacks on religious groups and restricted how kidnapping could be depicted. As one example of rejected art demonstrated, as enforced, the Code even forbade arrows from entering the body. In other words, the Code forbade the bread and butter of the classic Robin Hood story. Yet, this robber chief was considered a safe and harmless hero for a time when publishers were on their best behaviour.<2>

The comic book stories repeatedly stated that Robin Hood was not a thief. Instead nasty Norman knights who stole from peasants were labelled as the true thieves. In one tale Robin lectures a band of outlaws, "Begone, knave! Robbery is out of fashion hereabouts! The Merry Men keep the law here since Prince John and his barons prey on one and all!”<3> This tale shows that Robin Hood is not merely a force of natural law, but rather the Law of England itself -- only temporarily in exile. Similar – if not so direct – sentiments were expressed in the Richard Greene TV series of the day. But I doubt that Robin Hood fought man-sized hawks, panthers and apes in any other medium. The 1950s Robin Hood may not have been as dangerous as the Robin Hoods before or since, but these tales were more fun and inventive than what followed.

The conformist 1950s Robin Hood comics did not outlast the Richard Greene series. By the early 1960s, costumed superheroes returned to dominate the comics industry. There was little to distinguish Robin Hood from these morally-upstanding action heroes, but the adventures of Superman and Spider-Man took place in a more identifiable setting, modern America. Also, superheroes could be trademarked. Green Arrow and Robin the Boy Wonder - both inspired by Robin Hood - would make far more money in merchandising for DC Comics than the original archer would.

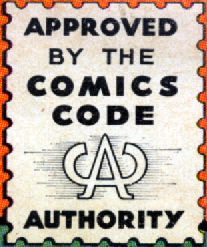

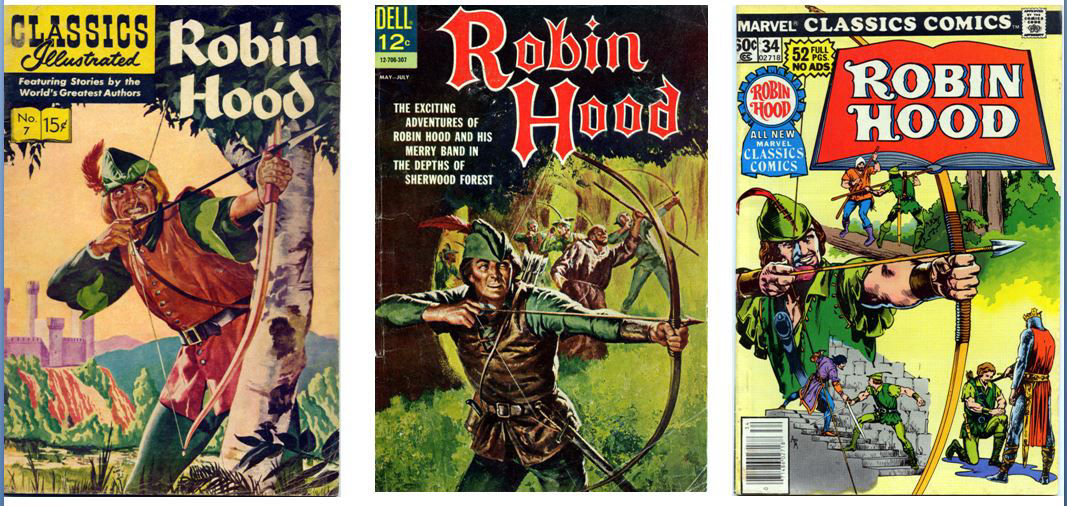

For nearly three decades, the legend lay fallow – largely restricted to cameos in time-travel adventures, reprints of 1950s stories, tie-in comics featuring the cartoon fox outlaw of the 1973 Disney animated feature, and the much-reprinted and imitated Classics Illustrated.

Classics Illustrated’s format of retelling the legend remained popular. Their revised version of Robin Hood – issue 7 – remained in print for more than a decade, inspiring competitors such as Dell and Marvel to also adapt classic novels including Robin Hood. The “Classic” style comics told Robin Hood’s life story, rather than the independent episodic adventures of the 1950s comic books. In this, they resemble children’s novels and Errol Flynn's film.

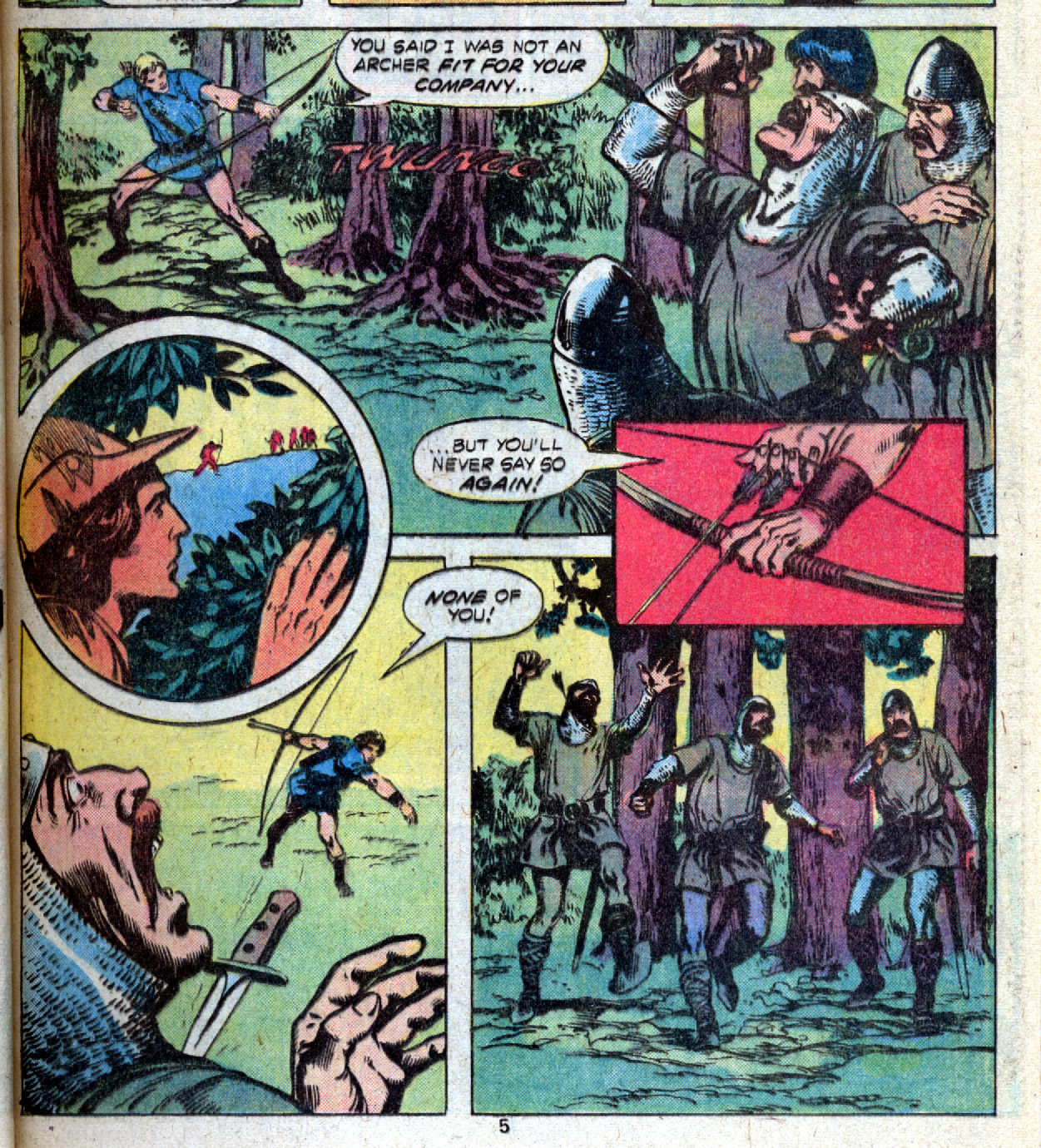

All three “Classics”-styled comics used a variation on the Progress to Nottingham origin story where Robin confronts crooked foresters. (By contrast, in most 1950s comics, Robin was the Earl of Huntingdon and King Richard’s appointed emissary.) Neither Classics Illustrated nor Dell subscribed to the Comics Code, claiming their standards were higher.<4> However, in both their versions, Robin Hood does not kill the foresters as he does in the ballad and Pyle’s novel.<5> Actually, it is the Code-approved “Classic” style comic where Robin acts as he does in other mediums. In Marvel Classics Comics #34 in 1978, Robin is more lethal than Pyle’s outlaw when he kills all but one of the foresters.<6>

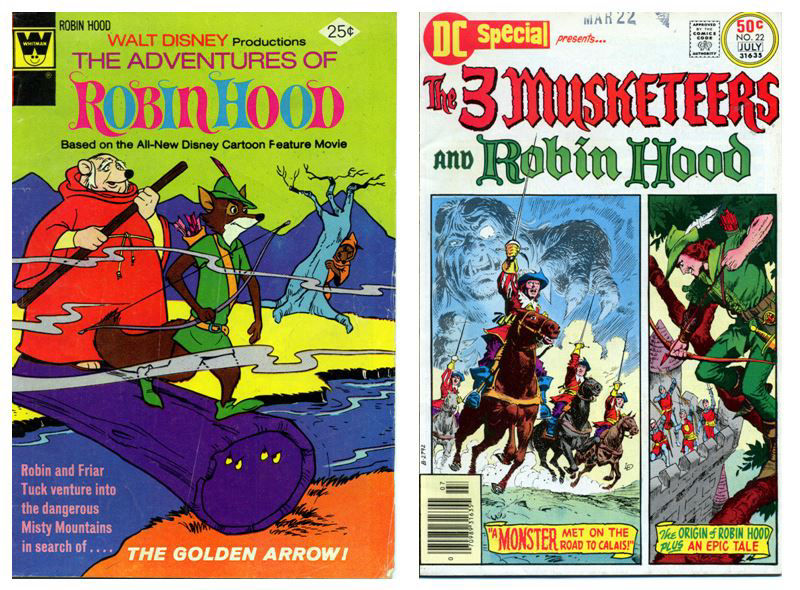

The 1970s offered audiences grimmer Robin Hoods in other mediums such as Wolfshead and Robin and Marian, and such filmic trends were also reflected in the comics. The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of popular superheroes – or anti-superheroes – such as Wolverine and the Punisher who had no qualms dispatching their enemies. The comic book readership was changing. In the 1950s, Robin Hood of the comics resembled the long-running superheroes who had dealt out death in their earliest appearances, but by mid-century had long-established codes against killing. However, starting in the 1960s, the comic book audience grew older, dominated now by people in their late teens or in college. Comics were now sold through comic book speciality shops, where the Comics Code – already modified from its 1954 version – carried little weight. Alternative publishers and even product lines from the big publishers produced comics without the code's seal of approval.<7> None of the Robin Hood comics from the 1980s onwards carried this restricting symbol.

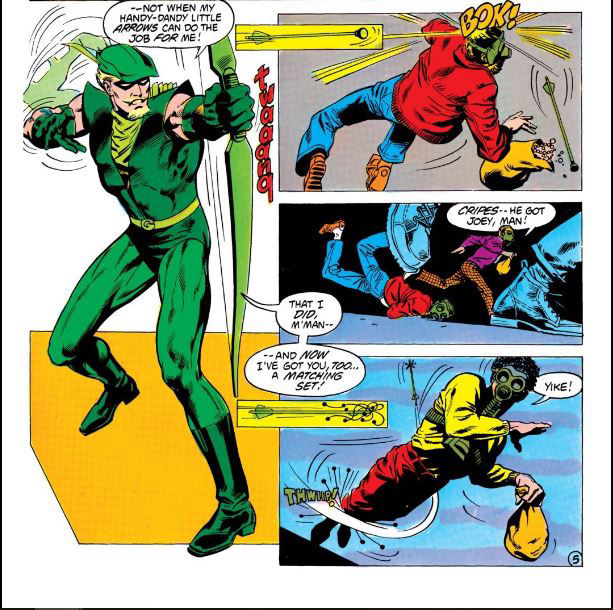

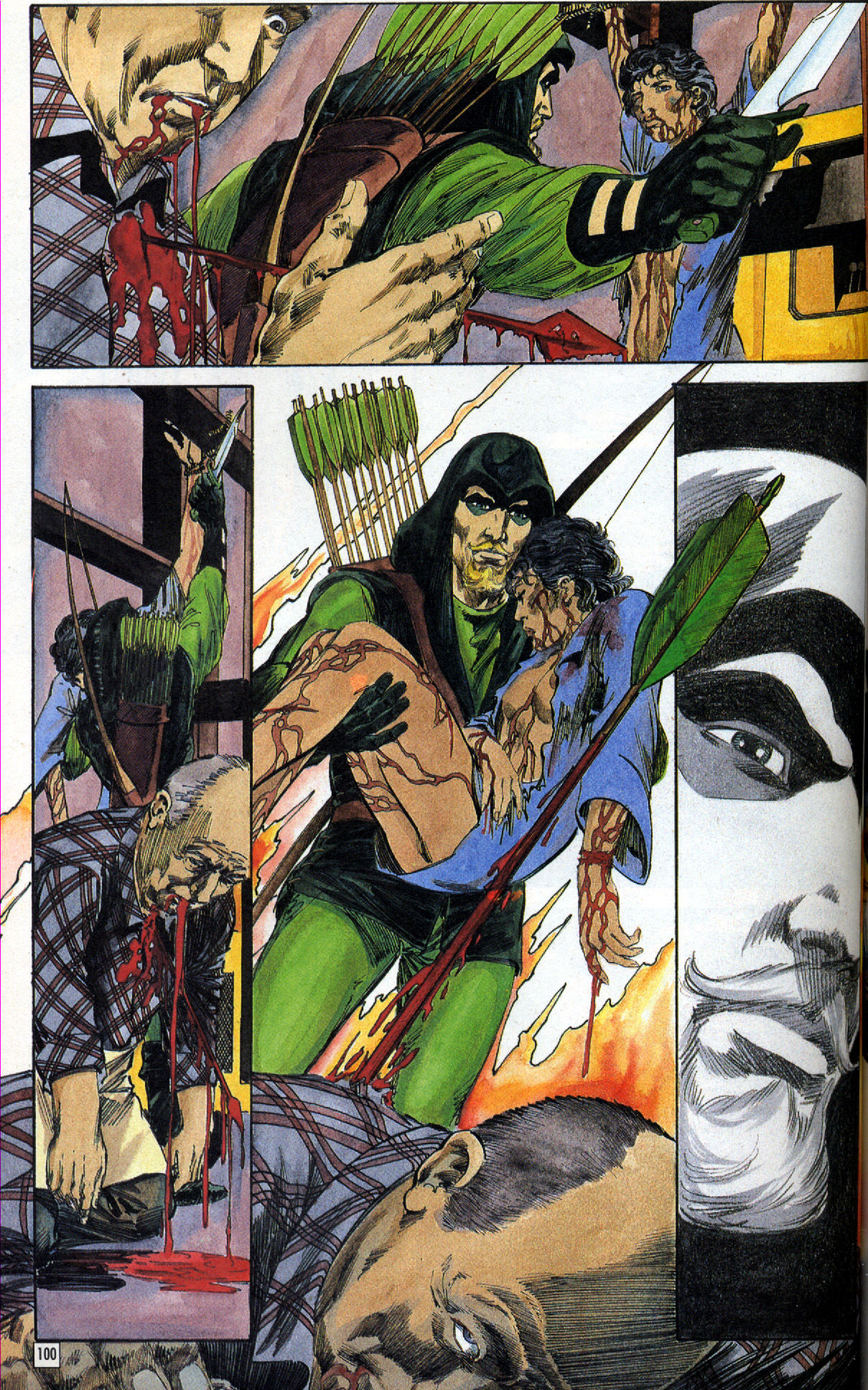

The mid-to-late 1980s saw even further darkening of comics with works that deconstructed heroic archetypes and tapped into the political zeitgeist of the Reagan/Thatcher years, such as Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – set in a dystopian future with a retirement age Batman that was more in line with the character's violent roots. Lesser imitations followed, including a reinvention of the Robin Hood-inspired hero Green Arrow. In 1987's Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters, he abandoned his traditionally non-lethal arrows – with boomerangs and boxing gloves on the tips – and replaced them with razor-tipped arrows. When Robin Hood emerged from his comic book exile, the medium had changed.

Green Arrow in 1983, with tricks arrows

Code-approved comic

Art by Don Newton and Dan Adkins

Green Arrow in 1987's The Longbow Hunters ditches trick arrows

No Comics Code Authority seal of approval

Story and art by Mike Grell

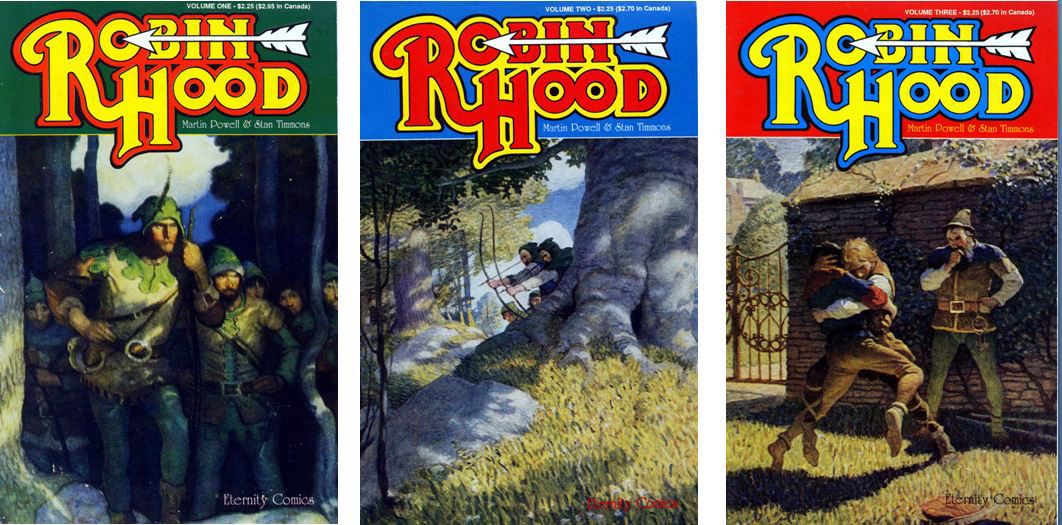

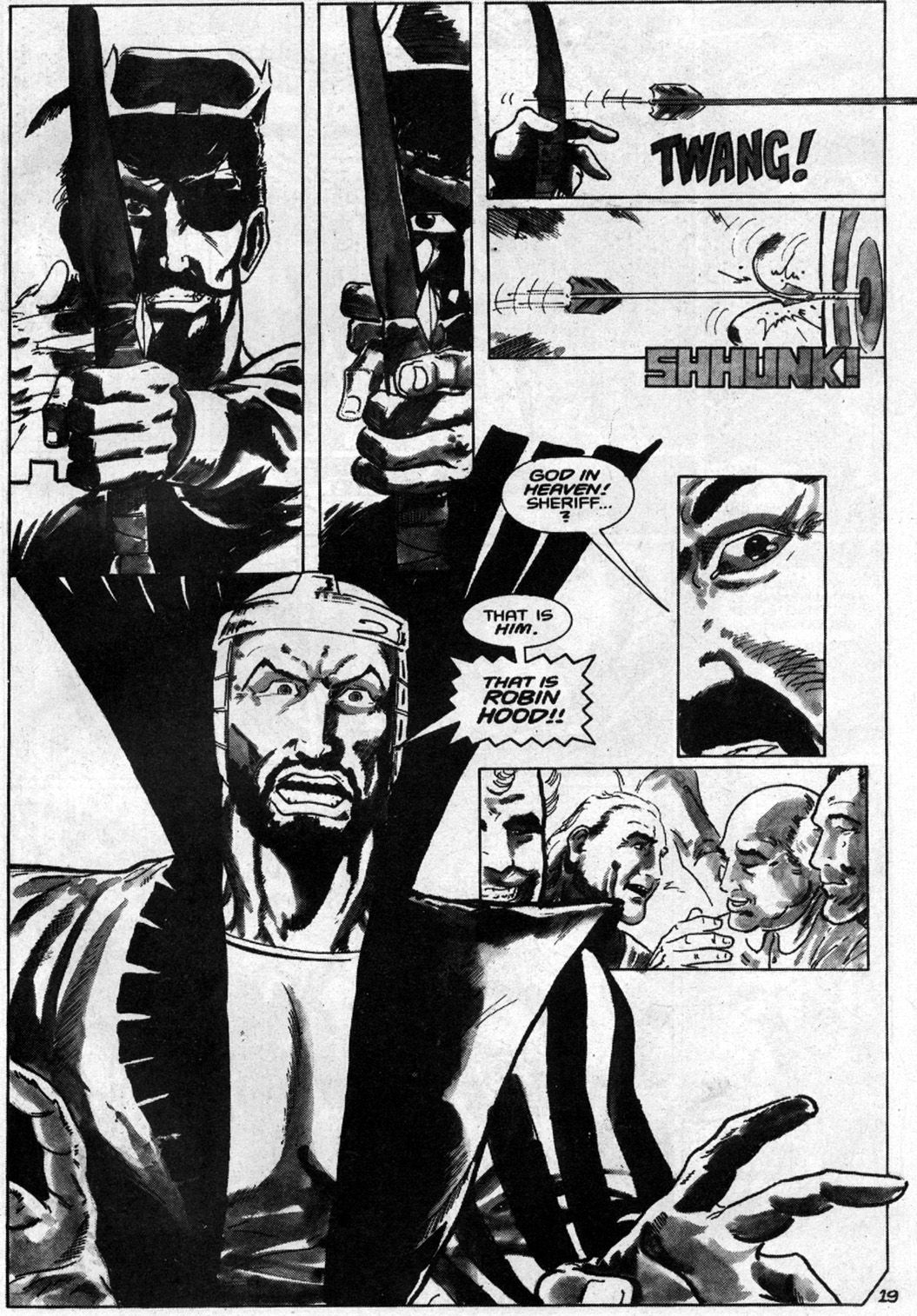

The four issue Robin Hood mini-series by Eternity Comics, published in 1989 and 1990, appears traditional with the covers reprinting N.C. Wyeth's classic paintings, acknowledgements “to the works of Howard Pyle, Paul Creswick, N.C. Wyeth and Sir Walter Scott"<8> , dialogue swiped from Errol Flynn, and a Robin Hood with blond hair and goatee that resembled both Wyeth's paintings and Green Arrow. The issues feature familiar scenes such as the quarterstaff duel, the stream crossing on Friar Tuck's back, the archery tournament, and once again the conflict with foresters.<9>

The difference, however, between the Eternity series and previous Robin Hood comics is evident on page 1, issue 1. Hired assassin Guy of Gisbourne has killed Robin's father, and vultures pick at the bleeding cadaver. It was more gruesome than previous Robin Hood comics had been, but the black-and-white art lessens the impact. While on some occasions, Robin ties his enemies to their horses and sends them home back to front or temporarily spare the sheriff<10> , the outlaws are also willing to kill their foes. For example, Little John gives the order “We can’t let them follow … kill them if you have to.”<11>

With the heavy promotion of the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, the legend had the biggest mainstream American exposure since the Richard Greene series. Publishers exploited that as the hero moved away from classic retellings into new and updated tales..

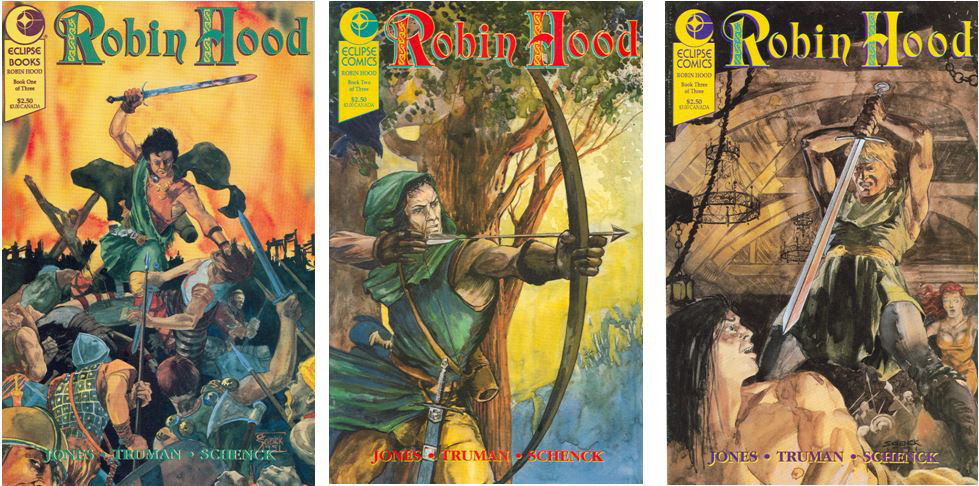

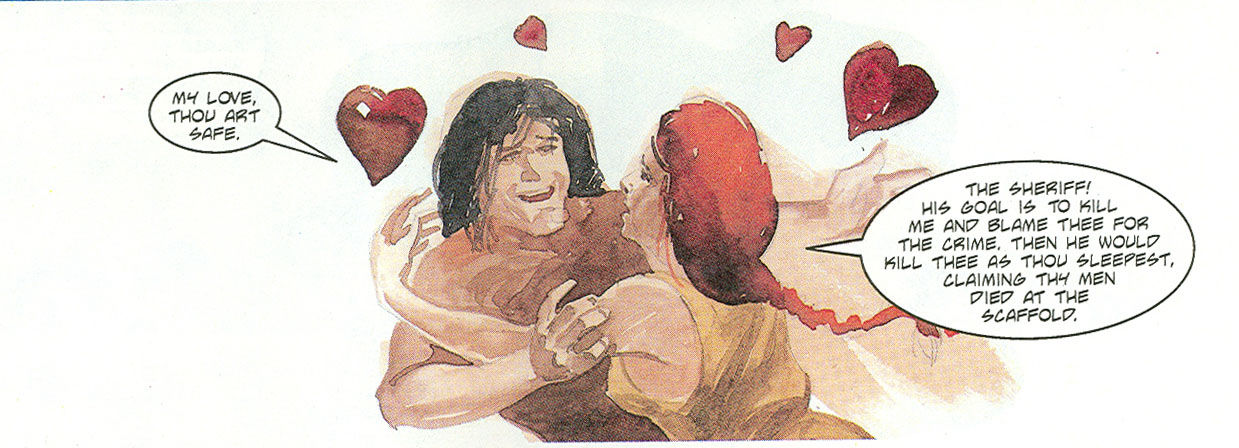

In 1991, Eclipse Comics produced a three-issue Robin Hood series written by Valarie Jones, which depicted the legend in pleasing watercolours. It features moments of romance, often written in the faux-medieval dialogue that Mark Twain called “Sir Walter’s Disease”. Robin proposes to Marian after their battle of mistaken identity and declares “Wilt thou stay with this poor green knight, this Lord of the Trees? Wilt thou sleep under the starry skies and call me husband?”<12>

However, the Eclipse comic series focuses not on flowery romance, but rather over the top violence – depicting more blood than in any Robin Hood comic before or since. Robin and his men kill often and in quite lurid ways such as one panel where Robin slashes two soldiers at once as red blood gushes out of the wounds.<13>

Showing a proactive heroine that is common to all Robin Hood comics – and most superhero comics -- of this time, even Marian sheds blood. “Give me thy blade, Marian. Thou hast been raised for manners, not war,” the sheriff says. “My father … taught me both!” Marian declares just before she drives a sword into the sheriff’s stomach.<14>

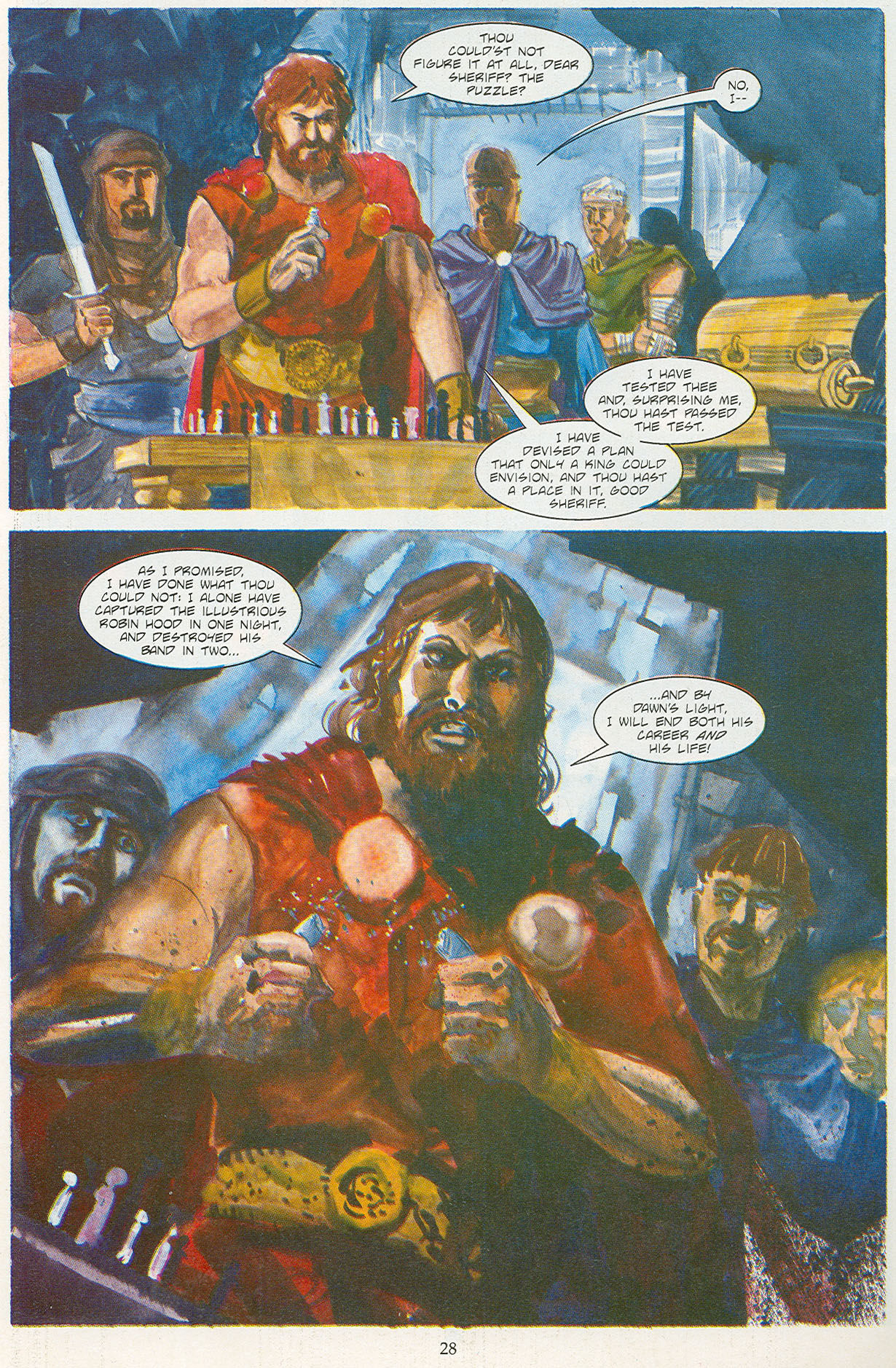

Good King Richard is not so good, and only pretends to pardon Robin. At the end of issue 2, the king reveals his true colours. “As I promised, I have done what thou could not. I alone have captured the illustrious Robin Hood in one night, and destroyed his band in two…. And by dawn’s light, I will end both his career and his life!”<15> King Richard is a moustache-twirling villain who sounds like a religious fanatic when he describes Robin’s presence in his hunting grounds as “a stain on its purity”.<16> After Robin escapes from the king’s treachery, he has a final encounter his monarch. Robin announces that Richard is king everywhere but Sherwood. “Here, I am the only king.” Then Robin repeats the king’s own words back to him, “When next we meet, I may have to kill thee” and shoots the crown off Richard’s head.<17> Robin’s defiance with a legitimate king is more radical than most Robin Hood stories although there were recent precedents in Robin and Marian, Robin of Sherwood and even Maid Marian and Her Merry Men.

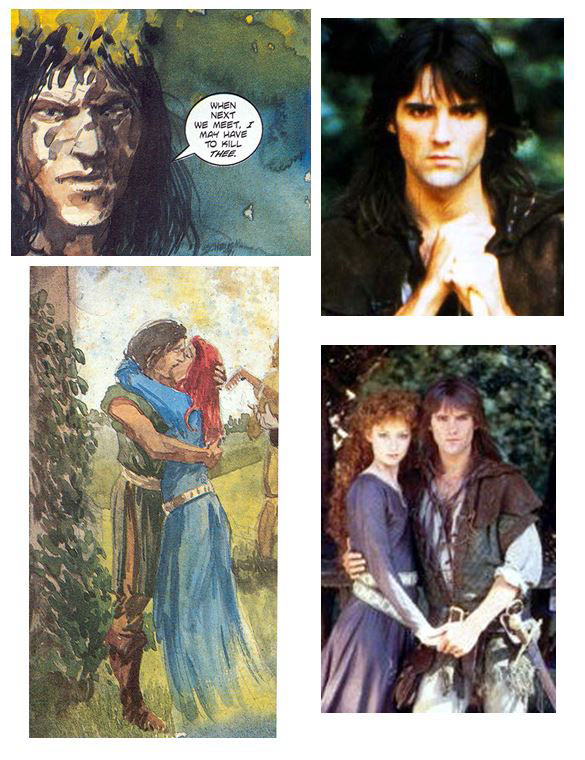

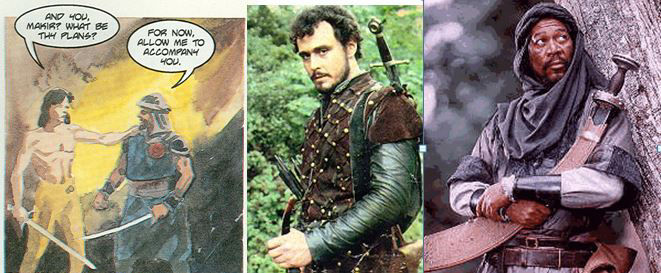

The Robin of Sherwood TV series is an influence on both the story and art, which depicts a Robin Hood with long dark hair who greatly resembles Michael Praed in some panels. Like the Costner film, the comic borrows from the TV series by adding a Muslim hero. Makir was a servant to King Richard, given to the king as part of a treaty that it is implied the king would break.<18>

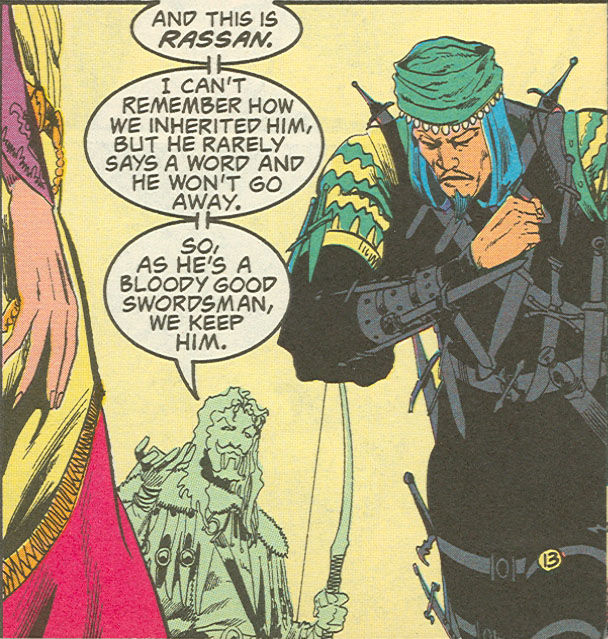

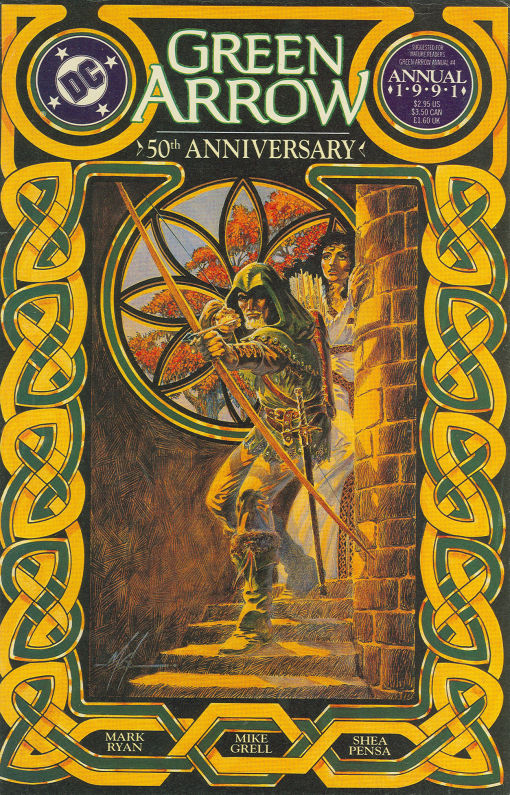

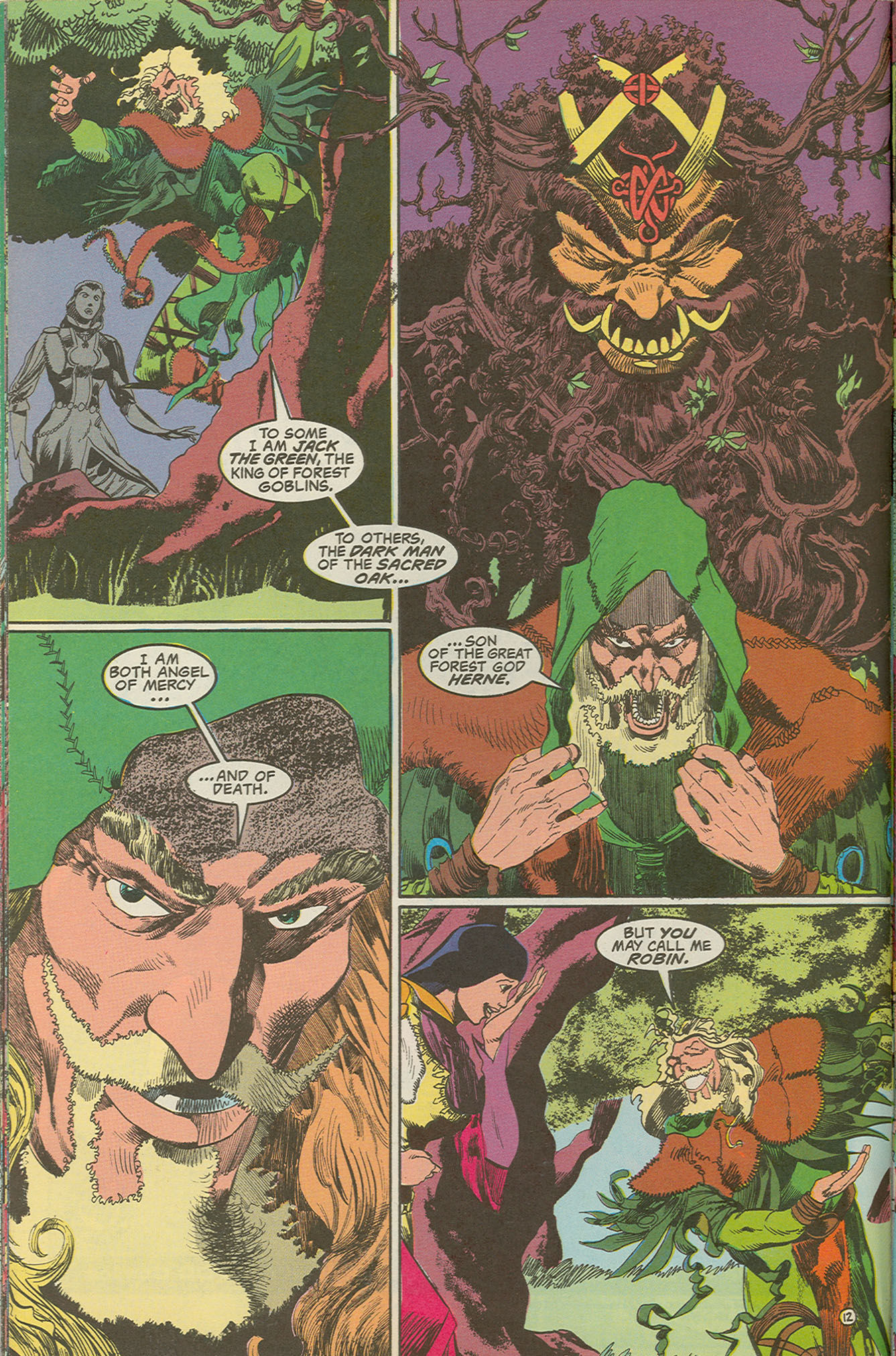

Eclipse was not the only publisher to include a Muslim among the Merry Men. The 1991 Green Arrow Annual #4 used the titular hero as only a framing device to tell a Robin Hood adventure. Among Robin’s band was a Muslim named Rassan,<19> (In this case, actor Mark Ryan who played a similar part on TV's Robin of Sherwood was the comic book’s co-writer.) The comic emphasizes the fantasy element of Robin of Sherwood, as Robin – a servant of Herne the Hunter<20> , as in the TV show – battles a skeletal sorcerer and a Welsh warrior woman. Perhaps as a nod to growing feminism in both comics and the Robin Hood legend, there is a female equivalent to Herne in Ellen, Guardian of Wells and Pathways.<21> Such fantasy elements appeared in other Robin Hood cameos in DC’s dark fantasy line Vertigo<22> , but there Robin Hood is used solely for his heritage value. These irreverent appearances lack a political edge.

Rassan in Green Arrow Annual #4

Mike Grell cover

However, despite their violence the other comics also lacked a political edge. The Eternity series was not that politically removed from the Robin Hood comics of the 1950s. Robin is still rebelling against the illegitimate rule of Prince John. Locksley Sr. was murdered by a rival seeking the sheriff’s job. Presumably, King Richard would have made Robin’s father the proper legal authority.<23>

The Eclipse Comics Robin Hood has a mission statement that feels political at first:

For we are rebels, soldiers in a war against the oppressive laws of church and state. Your brothers steal in the name of our God, and the well-born steal in the name of our king, but Robin’s men steal only that which should be free to all men.<24>

However, before he is disillusioned, Robin still supports the monarchy.. “I like not,” Robin says, “facing the king as a criminal rather than subject. It is ill-fitting to be called rebel when one loves his king.”<25> When the king does pardon Robin, the former outlaw refuses to hear an ill-word spoken about his king.<26> The Green Arrow Annual only borrows the fantasy elements of Robin of Sherwood, not the show’s anti-Thatcher politics. The best comics of the 1980s reacted to the politics of the day. DC Comics editor Kim Yale said that "Robin Hood is the complete antithesis of the greedy ‘80s"<27> , but many comic book Robin Hoods did not reflect that. Yale would edit the only Robin Hood comic to at least try to examine social and political issues that Green Arrow and other heroes dealt with in every issue.

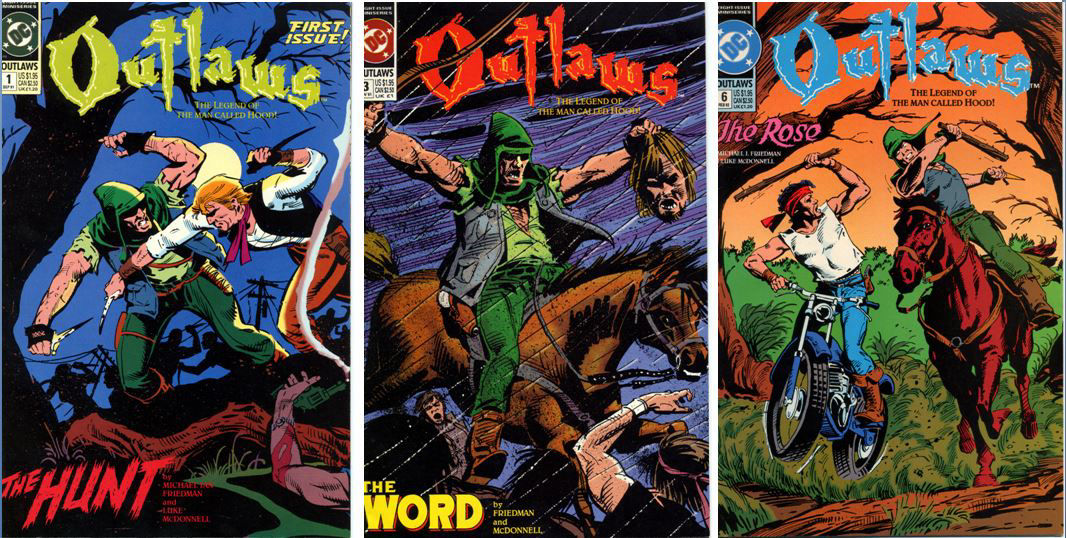

The most political Robin Hood comics do not feature the original outlaw but rather characters who have taken on his appearance. Green Arrow has been involved in political tales since the early 1970s. In 1991, DC introduced another updated Robin Hood figure in the eight-issue mini-series Outlaws: The Legend of the Man Called Hood. These stories are set a future America devastated by plague and returned to a feudal society controlled by the tyrant King John and his sheriff-like servant the Lord Conductor. Hood’s real name is not Hood. That would be too much of a coincidence, instead it is Lincoln Green. Hood/Green is a freedom fighter backed up by new versions of the Merry Men. His chief lieutenant – who replaces Hood upon his death in the final issue, is an escaped slave, a black man named Jess or Little Jess as Hood dubs him.<28> Other Merry Men include the minstrel Southpaw, an angry outlaw named Redbird and Helion – a former child concubine turned a warrior woman. Emotionally scarred, Hood and Helion have a relationship based on comfort rather than sex. The most intriguing character in the series is Father Bruno, a priest who raised Hood and secretly fostered and manipulated Hood’s interest in the outlaw legend.

Outlaws has the more violent feel of the 1980s and 90s comic books, but it has far less blood and far more politics than Eclipse’s version. Many of the most violent scenes are shown in silhouette, such as when Southpaw kills his lover after she betrayed the band<29>, when Helion is shot by the Lord Conductor and when Hood exacts his revenge.<30>

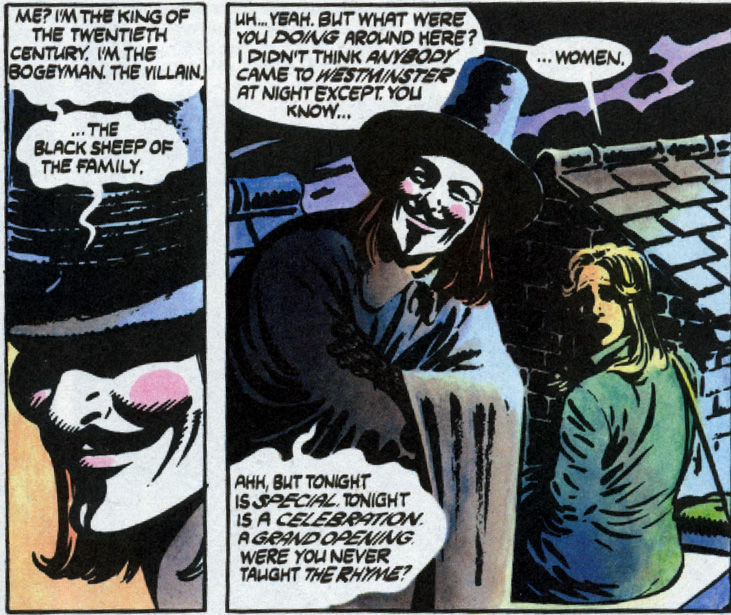

In that it is a comic book set in a fascist-controlled future with a rebel dressed as a past hero, Outlaws has much in common with the ground-breaking V for Vendetta. The 1980s series by Alan Moore and David Lloyd features a terrorist hero waging a war against a corrupt regime, this time a fascist Britain. However, V is a better-written comic and far more unsettling – closer to the original Robin Hood of the ballads.

Hood expresses doubts about both his mission and his abilities, such as when some village peasants refuse to support his crusade he tells Little Jess, “Somehow, I know, I’m failing them. They don’t respond. My fault for not living up to ‘the legend.’”<31> Later when he finally has the people on his side by the winning an archery tournament, Hood remarks “I’m frightened, Jess … Until the day of the tournament, I was pursuing the legend. Now I feel as though the legend is pursuing me.”<32> The film and television Robin Hoods of Michael Praed, Jason Connery and Kevin Costner also doubt their mission. But the Robin Hood of the early ballads never doubted nor feared, and neither does V. One might suggest that self-doubt makes Hood (and Robin Hood) a more mature character, but it also makes him a safer character. It is the fanatic who never doubts. Also, Hood has a perpetual stone-faced grimace. Father Bruno, as Jess accuses, has “emptied his life of laughter – of joy.”<33> But V, wearing his paper mache Guy Fawkes mask, is always smiling. ]It lends a trickster vibe, like Robin Hood used to have. V is a trickster when he is blowing up the Old Bailey or hijacking TV broadcasts threatening to “fire” the human race. V’s humour is disturbing and adds a layer of ambiguity to keep the hero as a trickster when committing crimes.

Hood from Outlaws

V for Vendetta

V for Vendetta and Outlaws also have different approaches to authority. Outlaws suggests, like many modern Robin Hood stories, that there will be a restoration of traditional order. Father Bruno explains to Jess that Hood is needed because “people who’ve served so long under a monarch can’t learn overnight to rule themselves. They’ll need someone they can look up to – someone who can offer them law and government until they come of age.”<34> Not so with V for Vendetta, where the new V tells the crowd, “Since mankind’s dawn, a handful of oppressors have accepted the responsibility over our lives that we should have accepted for ourselves.” V is not merely condemning one corrupt government, but the history of all governments. There is no legitimate government for V to restore. “In anarchy,” V explains, “there is another way.” The terrorist departs by saying “Tomorrow, Downing Street will be destroyed, the Head reduced to ruins, an end to what has gone before. Tonight, you must choose what comes next. Lives of our own, or a return to chains. Choose carefully.”<35> The possibilities created V seem broader and less reassuring than those offered in the world of Outlaws. Despite that Hood does decapitate a foe as in the early ballads, Outlaws still feels like a particularly violent children’s story.

In the mid-90s, longing for retro-charm, elements from the 1950s and 60s comics began to reassert themselves although filtered through modern sensibilities. In other mediums, Prince of Thieves, The New Adventures of Robin Hood and Princess of Thieves offered an absent but good king and a status quo more reassuring than Robin Hood films and TV series of the 1970s and 80s. When two more start-up publishers launched Robin Hood-related comics, the stories were safer than Outlaws or Eclipse’s Robin Hood.

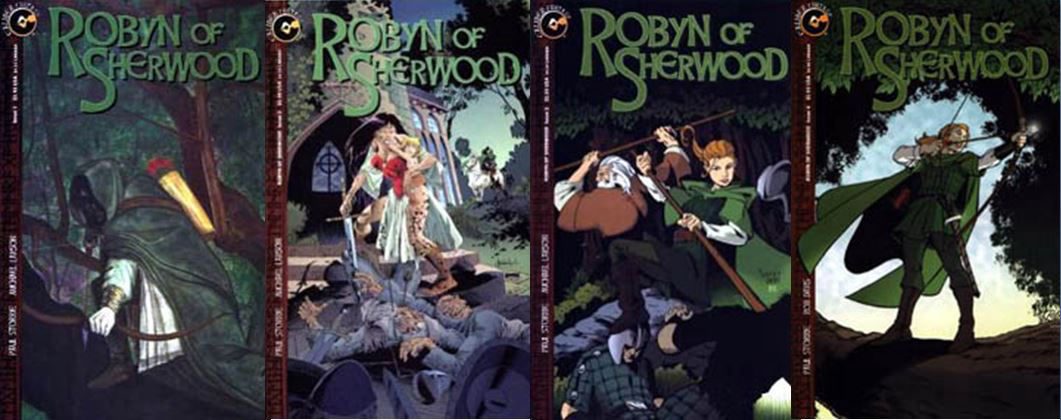

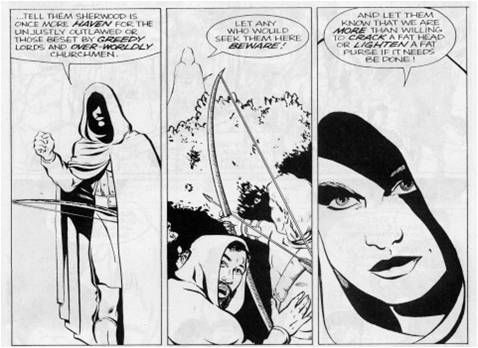

Robyn of Sherwood was published by Caliber Comics in the late 1990s. Written by Paul Storrie, it features the adventures of Robin Hood and Maid Marian’s daughter who fights an evil King John. The female Robyn declares “The king and his servants do what they will, with no care for law, and even less for justice.” With her concern for law, Robyn expresses concepts similar to those in 1950s Robin Hood comics.

While there is no good King Richard present to offer higher authority, there is the memory of former king Henry II (the king in Pyle’s novel). An imprisoned but newly defiant Will Scarlet tells King John: “Why do you think he was so devoted to the law, to making sure that all had justice? A good ruler protects and nurtures his people. He does not crush them beneath his heel.”<36>

In Robyn’s first appearance, she rescues Little John by fatally shooting soldiers in the head and chest.<37> However, in the second issue, Robyn refuses to kill soldiers that the outlaws have captured. She explains to the hot-tempered Tanner, “We’ll win no one’s trust by stacking up bodies like cord wood.” This schizophrenic approach to killing is common in the legend. As Robyn observes, “my way is my father’s.”<38>

After writing about the daughter, Storrie wrote comics about the original Robin Hood for Moonstone Books. Billed as a “director’s cut” of the ballads, Robin Hood and the Minstrel tells the Allan-a-Dale story with new action sequences added. In one such sequence, Robin aims to kill the old knight Stephen of Trent, but accidentally shoots his squire instead. However, Robin is happy that Will Scarlet dispatched most of Trent’s men without killing them. “There was blood enough shed this day and I am not one for spilling it cold in any event.”<39>

In 2004, Minstrel was reprinted in a collection with the script for “Robin Hood and the Knight” (an updating of the story from the Gest) and “Robin Hood and the Jailer”, a new tale. “Jailer” begins when Robin spares the life of Nottingham’s new jailer. “How absurdly typical of Robin,” the Sheriff muses.<40> Marian is trapped in the dungeon. But as in the 1989 Eternity series, while Marian might be a damsel in distress, she escapes on her own, by slashing the jailer.<41> In an interview, Storrie notes the Howard Pyle tales are “my touchstone for Robin Hood to this day.”<42> However, Marian was firmly off-stage in Pyle’s novel. Storrie follows other Robin Hood stories of the 1980s and beyond by having an active Marian, reminiscent of the stronger role for female superheroes. Yet, when she escapes from prison, Marian is clad in an outfit that would make Xena, Warrior Princess blush. Like many comics of the day, this tale mixes feminism with titillation.

For all the maturing comics did in the 1980s, the Robin Hood legend did not grow up with them. It became more violent than his previous comic incarnations had been, but despite surface rebellion, the character was a mostly reassuring hero. If the trickster and riotous ways of the original Robin Hood could return along with the violence, then we might have Robin Hood comics that are truly adult.

<1> Wright, Allen W. "'Begone, knave! Robbery is out of fashion hereabouts!': Robin Hood and the Comics Code presented at the 2nd International Conference for Robin Hood Studies held in Nottingham, England, July 1999. Evidently forthcoming in British Outlaw Traditions ed. Helen Phillips, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2006.

<2> “Comics Magazine Association of America Comics Code 1954” In Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, Amy Kiste Nyberg, 166-9. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississipi, 1998. While she does not mention Robin Hood comics specifically, Nyberg’s book provides an excellent background to the history of the Comics Code. Her example that “the code was interpreted to mean that arrows, hatchets, or bullets were not to be shown piercing the body” is on page 115.

<3> [Uncredited] (w) and [Frank Bolle] (a). "Sir Robin Hood.” Robin Hood #4 (May 1956), Sussex Publishing Company, Inc. [Magazine Enterprises]: [p. 9] (2)

<4> Nyberg. 116-7.

<5> [Uncredited] (w) and [Uncredited] (a). “Robin Hood.”, Classics Illustrated #7 [Ed. 16, HRN 153] (1959) [Revised version of #7, with updated story and art appeared with Ed. 14, 1957] Gilberton Company, Inc.: pp.2-3 (Robin merely punches the foresters) and [Uncredited (w) and Uncredited (a)] Robin Hood (May - July 1963), Dell Publishing Co.: p.2-3 (one of the foresters is accidentally killed by another, and Robin Hood is blamed – the narration still hedges their bets though in saying “Rightly or wrongly, the king’s foresters thought Robin had killed one of them”.

<6> Moench, Doug (w), Rudy Messina and Alfredo Alcala (a). “Robin Hood.” Marvel Classics Comics #34 (1978), Marvel Comics Group, pp. 5-6. (I should also note that this comic was published under a Comics Code that was slightly modified in 1971, although the basic provisions remained the same as the 1954 version. It would appear that arrows could now be shown to pierce flesh, albeit slightly obscured.

<7> Nyberg, p. 129-54

<8> Powell, Martin (w), Stan Timmons (a) "The Thieves of Sherwood Book One" Robin Hood #1(Aug. 1989), Eternity Comics, p. 8.

<9> Little John duel: Issue 1, pp. 15-17; Friar Tuck: Powell, Martin (w) and Stan Timmons (a) "The Thieves of Sherwood Book Two" Robin Hood #2 (Oct. 1989), Eternity Comics, pp.16-19, Archery contest: Powell, Martin (w), Stan Timmons (a) "The Thieves of Sherwood Book Three" Robin Hood #3 (Feb. 1990), Eternity Comics, pp.12-20. Recycled dialogue includes "Not Robin Hood?! Then I'm right glad I fell in with you!" "'Twas I who did the falling in." (issue 1, p. 17) and a starvation/taxes exchange on p.11.

<10> Eternity, Issue 1, p. 12 and pp. 26-7

<11> For example, Robin killing a forester (the sheriff’s brother), issue 1 p.5 although Robin expresses regret. Issue 1, p. 24, Issue 2 p. 4 and issue 3 p. 6

<12> Jones, Valarie (w), Christopher Schenck (illustrator) and Timothy Truman (layouts). Robin Hood #2 (Sept. 1991), Eclipse Comics, p.13

<13> For example: Jones, Valarie (w), Christopher Schenck (watercolors) and Timothy Truman (layouts). Robin Hood #1 (July 1991), Eclipse Comics, p.5 (Robin slashes two men at once while a Merry Man gets stabbed through the heart), issue 1 p. 11 (panel 1: Allan-a-Dale stabs a guard through the heart, panel 2: Tuck smashes a guard’s jaw to much blood, panel 3: Sir Guy hacks peasant’s neck), issue 3 p. 21 (panel 4: Robin stabs Guy through the heart)

<14> Jones, Valarie (w), Christopher Schenck (illustrator) and Timothy Truman (layouts). Robin Hood #3 (Dec. 1991), Eclipse Comics, p. 10. Marian kills a guard, shedding much blood (as seen in slide) on p. 19 of issue 3. Even in the first issue, Marian started a fire that saved the outlaws (p. 6)

<15> Eclipse. Issue 3, p. 28 (slide)

<16> Eclipse issue 3, p. 2

<17> Eclipse issue 3, p.26

<18> Eclipse issue 3, p. 6

<19> Ryan, Mark, Mike Grell (w) and.Shea Anton Pensa (a). “The Black Alchemist.” Green

Arrow Annual #4 (1991). DC Comics, p. 13

<20> GA Annual, p. 12

<21> GA Annual, pp. 20 - 21

<22> Jenkins, Paul. (w) and Sean Phillips (a). “Critical Mass Part 2: Troubled Waters.” Hellblazer #93, (Sept. 1995) DC Comics [Vertigo]; Willingham, Bill (w), Marc Laming (p) and John Stokes (i). “The Further Adventures of Danny Nod – Heroic Library Assistant.” The Dreaming #55, (Dec. 2000) DC Comics [Vertigo]; Willingham, Bill (w), Craig Hamilton (p), (i and layouts) P. Craig Russell. Fables: The Last Castle (2003) DC Comics [Vertigo]

<23> Eternity, issue 1, p. 7

<24> Eclipse issue 1, p. 28

<25> Eclipse issue 1, p.22

<26> Stutely declares “I have no wish to play king’s favourite toy and fight for his enjoyment.” “Stutely, we are not toys.” Eclipse, issue 2, p. 16

<27> Yale, Kim. “Editorial”. Outlaws #2 (Oct. 1991) DC Comics.

<28> Friedman, Michael Jan (w) and Luke McDonnell (a). “The Wheel.” Outlaws #1 (Sept. 1991) DC Comics, p. 15

<29> Friedman, Michael Jan (w) and Luke McDonnell (a). Outlaws #6 (Feb. 1992) DC Comics, p. 16

<30> Friedman, Michael Jan (w) and Luke McDonnell (a). Outlaws #7, (March 1992) DC Comics, pp. 18 - 19

<31> Outlaws, Issue 3, “The Word”, p. 10

<32> Outlaws, Issue 6, “The Rose”, p.3

<33> Friedman, Michael Jan (w) and Luke McDonnell (a). Outlaws, issue 8, “The Deception” (April 1992) DC Comics, p. 16

<34> Outlaws, issue 8, p. 18

<35> Moore, Alan (w) and David Lloyd (a). V for Vendetta ed. K.C. Carlson and Karen Berger. NY: DC Comics, 1990, p. 285

<36> Storrie, Paul (w) and Rob Davis (a). Robyn of Sherwood #4 (1999) Caliber Comics, p. 10

<37> Storrie, Paul (w), Michael Larson (p) and P. A. Dery (i). Robyn of Sherwood #1 (1998) Caliber Comics, [p. 14-5]

<38> Storrie, Paul (w) and Michael Larson (a). Robyn of Sherwood #2 (1998), p.4

<39> Storrie, Paul D., Rich Gulick (p) and Steve Bird (i). Robin Hood and the Minstrel. (2001) Moonstone Books, pp. 45 and 48.

<40> Storrie, Paul D. (w), Nate Melton (p) and Chad Bunt (i). “Robin Hood and the Jailer” in Robin Hood. (2004) Moonstone Books, p. 7

<41> “Jailer”, p. 34

<42> Interview with Allen W. Wright, http://www.boldoutlaw.com/robint/storrie1.html Conducted in July 2001.

A note about the notes (w) stands for writer, and (a) is for artist. But often some distinction is required in the art. (p) is for penciller – the primary artist on comics and (i) is for inker, who goes over pencil art in inks to add mood, shadow and other elements.

Comics were often released a few months before the publication date, a holdover from the days when they wanted have unwary retailers keep the comics on the shelves a bit longer. In the case of V for Vendetta, the story was serialized in the 1980s first in the British magazine Warrior and then in the late 1980s reprinted and then completed by DC Comics. The 1990 date is the publication date for the collected edition.

Contact Us