John Chandler traced the connection between Robin Hood and Batman's earliest adventures in his article "Batman and Robin Hood: Hobsbawm's Outlaw Heroes Past and Present" which appeared in the collection Robin Hood in Greenwood Stood: Alternity and Context in the English Outlaw Tradition edited by Stephen Knight.

Chandler ties Batman to the "noble robber" model conceived by Eric Hobsbawm. However, although Chandler mentions various points in Batman's decades-long career, he restricts his detailed analysis to the first eleven appearances of Batman, stopping with Detective Comics #37. He lists the creation of Robin the Boy Wonder as one of the contributing factors to strip Batman of his early outlaw status.

And while that may be true to an extent, it was a mistake not to look at some of the early adventures of the Dynamic Duo of Batman and Robin. There is Robin Hood content lurking in some of the Boy Wonder's adventures too.

So, this section looks at a few more of these early Batman tales including Robin's origin and first appearance in Detective Comics #38, cover dated April 1940.

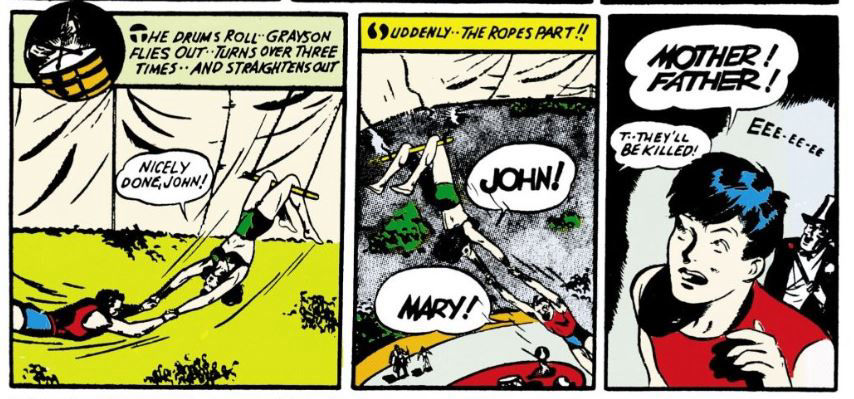

The first story opens "Legend: Robin, the Boy Wonder and how he came to be an ally of the Batman." A similar legend had preceded the Batman's origin a few months earlier. The story opens in a small town outside the nameless big city that within a year would acquire the name Gotham City. We are introduced to the Haly Circus's star act -- "the Flying Graysons, father, mother and young son, Dick".

After the show, Dick overhears a couple of gangsters trying coerce circus owner Haly into paying protection money. Haly refuses and a crook threatens "accidents will happen".

The scene shifts to the next night. Batman's alter ego is in the audience as the ringleader announces the Graysons will perform their famous triple spin. And then an "accident" happens - the trapeze ropes come apart.

The horror of the Graysons' deathly fall is seen through Dick's horrified reaction. The clown wipes away tears as the ringmaster confirms that Dick's parents are dead. Later, the gangster returns to shakedown Haly, and he gives in. Young Dick is listening at the keyhole and vows to go to the police. A mysterious voice tells him "No, son. Not yet!"

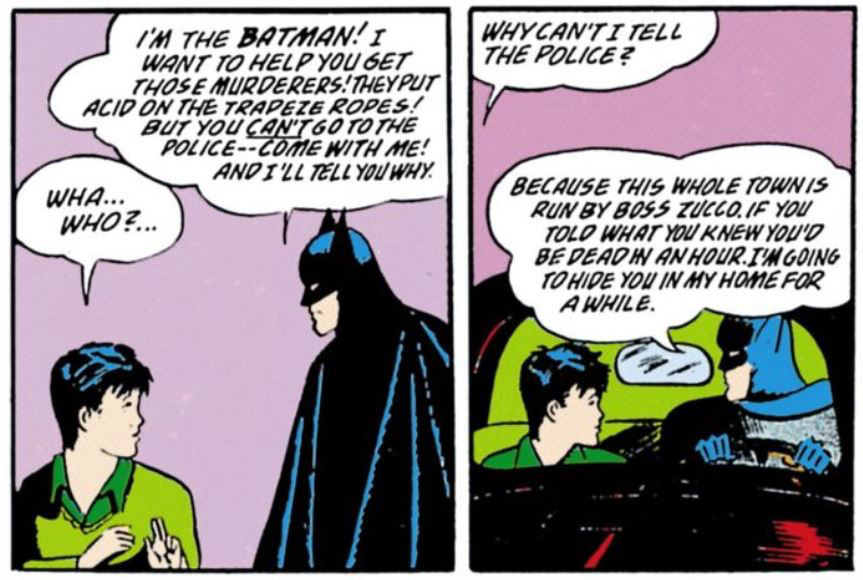

Dick turns around and see the Batman who says he wants to help Dick, but he can't go to police yet. Once in the Batman's car, the caped hero explains why Dick can't go to the police. "Because this whole town is run by Boss Zucco. If you told what you knew you'd be dead in an hour." It seems the cops in this town are about as trustworthy as the Sheriff of Nottingham.

The Batman offers to hide Dick in his home, and then confides "My parents too were killed by a criminal. That's why I've devoted my life to exterminate them." Dick begs to go with him, and seeing their common bond, the Batman agrees even though he warns it is a "perilous life".

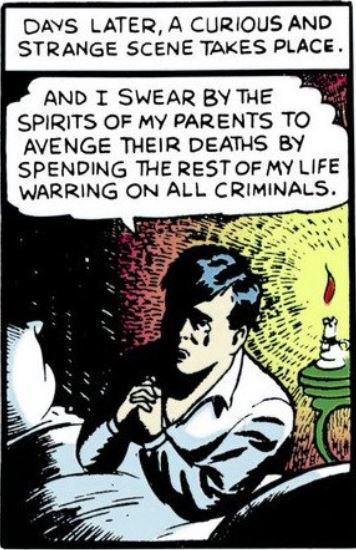

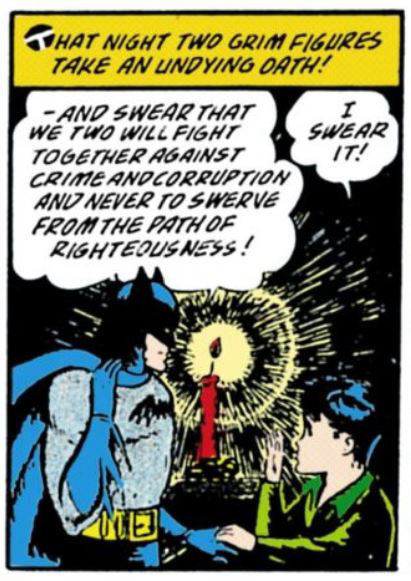

Then in another replay of the Batman's origin, Dick Grayson swears a solemn oath with the Batman -- to "fight together against crime and corruption." Errol Flynn's Robin Hood also had the Merry Men swear an oath to fight against tyrants and help the oppressed in the popular 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Young Bruce Wayne swears an oath in Batman's origin from Detective Comics #33

The Batman and young Dick Grayson swear an oath in Robin's origin from Detective Comics #38

The Batman's origin showed how Bruce Wayne trained his mind and body to be able to fight crime. And we have similar scenes here.

The training begins with trapeze work -- something Dick says he's been doing since he was four years old. Bruce Wayne admits that Dick could probably "teach me a trick or two." The training moves onto boxing and ju jitsu.

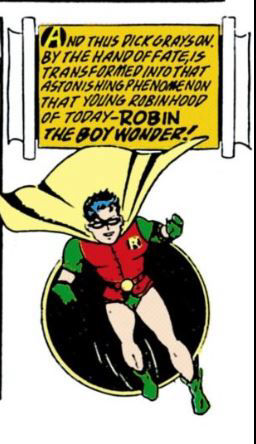

Then it comes to time to debut Dick Grayson's new costume and new name -- "that astonishing phenomenon, that young Robin Hood of today -- Robin the Boy Wonder."

The caption on the next page tells of months of work and study have passed. And Bruce Wayne tells Dick Grayson it's time for him to return to that small town -- disguised as a newsboy. When a disguised Grayson starts selling papers, he's approached by two thugs demanding their cut.

Dick checks in with Bruce Wayne, and the Batman tells him to continue to act frightened.

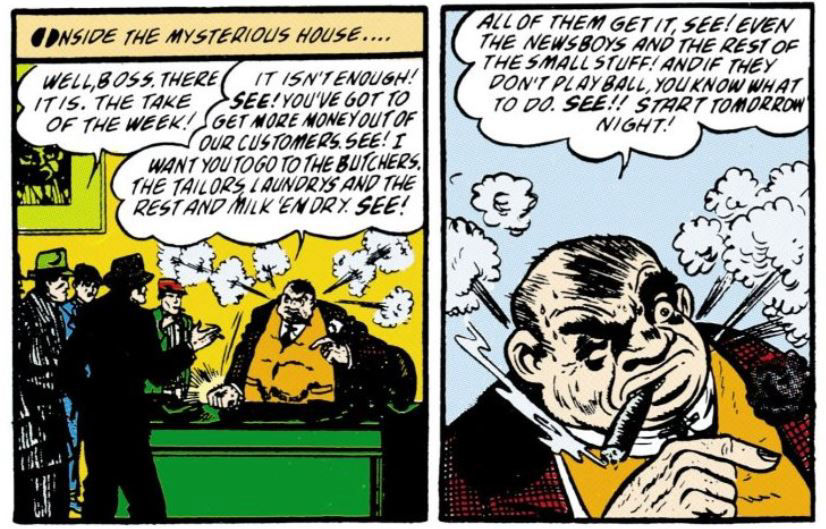

The next night after the thugs shake Dick Grayson down for his paper money money, the Boy Wonder falls the thugs back to their hideout. There, Dick overhears Boss Zucco planning to milk all the business of the town dry -- butchers, tailors, laundrys and even the newspaper boys. Zucco is the stereotypical gangster, adding the word "see" to the end of sentences, like a bad imitation of famed gangster actor Edward G. Robinson.

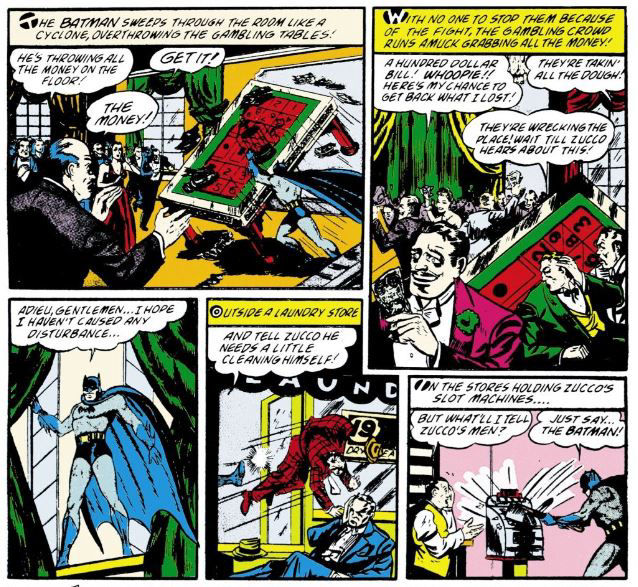

After hearing the schemes of this wannabe Little Caesar, Dick reports back to the Batman. And we see the Batman stop Zucco's hoods from fleecing the local butcher and tailor. Then, the Batman goes to bust up one of Zucco's gambling houses.

Very similar montages happened in both the 1922 Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood silent movie and the 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood starring Errol Flynn. The Batman throws the gambling money on the floor and the patrons grab at it. It's as if the Caped Crusader is robbing from the rich and giving to the poor.

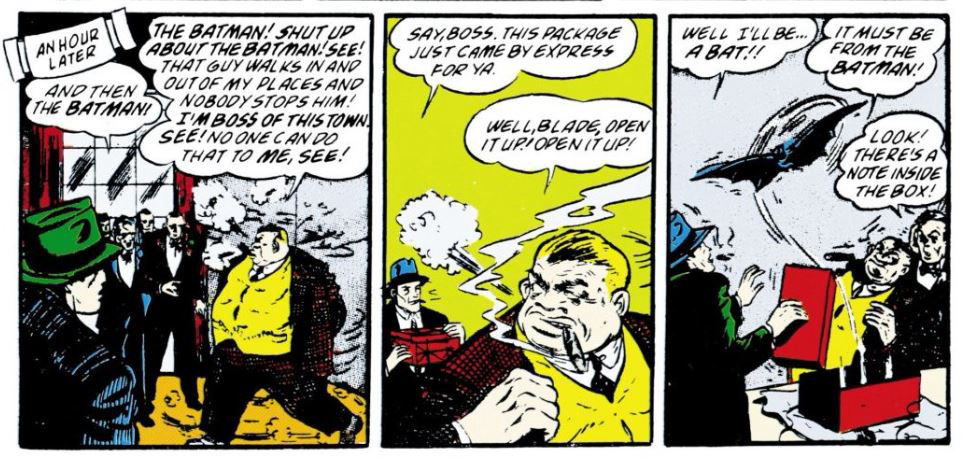

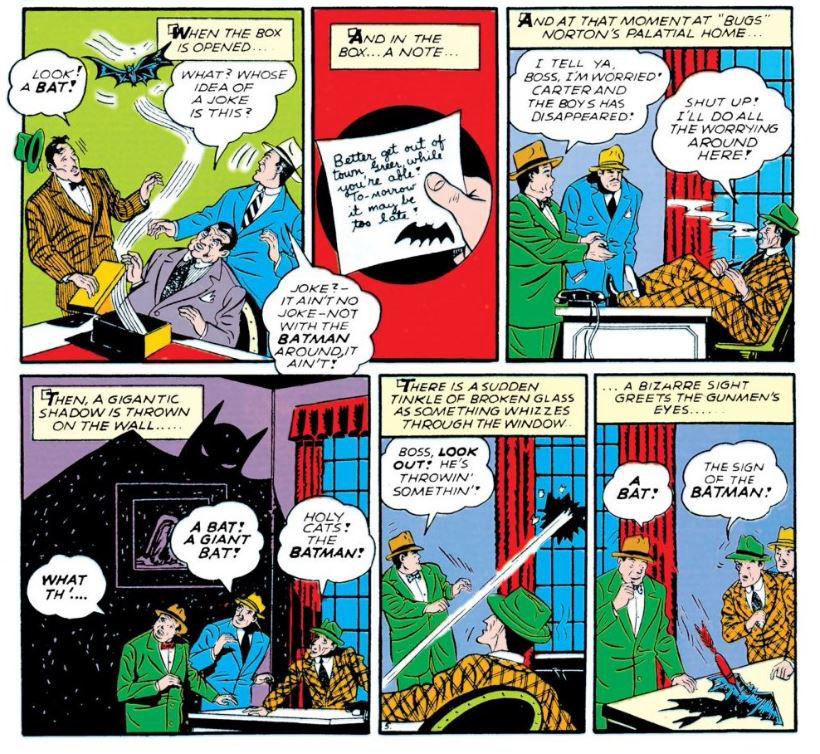

In both the 1922 and 1938 movies, the bad guys discuss what to do about Robin Hood, and they are shocked to find an arrow landing in their presence. In the comic, the Batman sends Zucco a box containing a live bat.

An arrow warning from Robin Hood in 1922's Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood

An arrow warning from Robin Hood in 1938's The Adventures of Robin Hood

Also, inside the box is a note from the Batman. He's aware of Zucco's plan to squeeze money out of the construction companies working on the Canin Building, and warns Zucco to stay away as the building is under the hero's personal protection. Zucco takes the bait and plans to go to the building personally, to show the Batman who's boss. Robin clings to back of Zucco's car and follows them to the construction site.

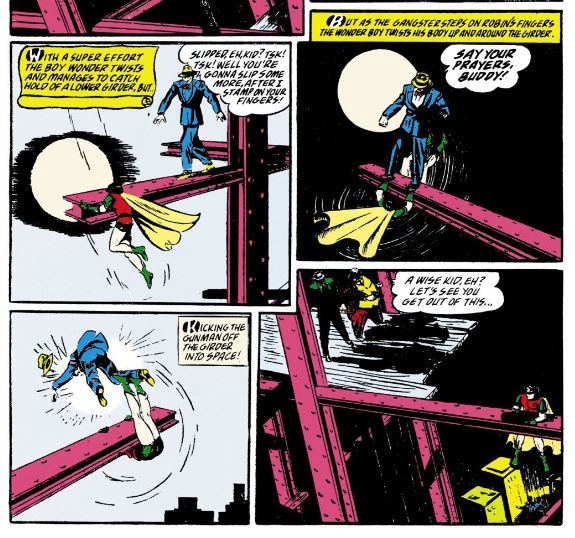

At the skyscraper construction site, Robin attacks Zucco's goons on the girders. In the midst of the fight, Robin slips and clings to a girder as a crook stamps on his fingers. Robin swings his feet around and kicks the crook off the girder and "into space" (which presumably would kill the criminal).

If Robin's appearance is supposed to have brighted Batman's dark ways, Robin's action reflect the lethal justice that the Batman dispensed in his early adventures.

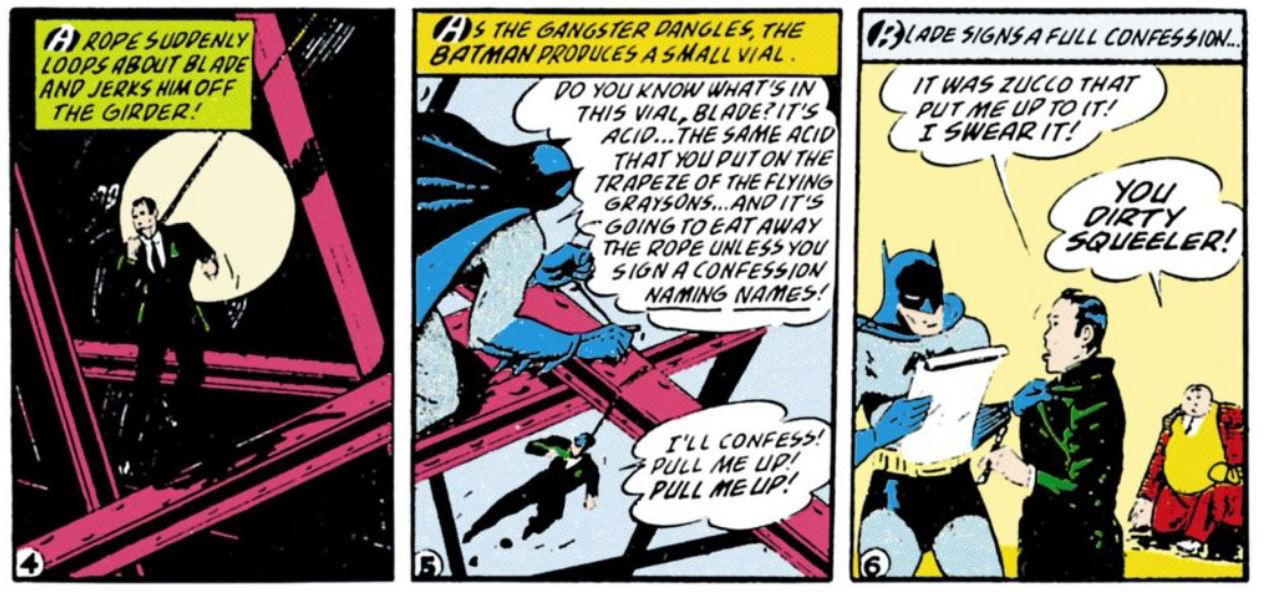

The Batman swings onto the scene to help his young partner. He throws a noose around a mobster's neck. Then the Batman produces a vial of acid -- the same kind that was used on the Flying Graysons' trapeze ropes -- and threatens to burn through the noose unless the goon confesses.

Later versions of Batman will also force confessions from criminals. But in the later comics, the reader is left with the sense that Batman is bluffing. In this case, I don't think the Batman is bluffing.

After the crook signs his confession, Zucco attacks the "dirty squealer", tearing him away from the Batman and throwing him off the partially completed skyscraper. It would seem that the illegally obtained confession is useless.

But it turns out that the Batman had a morbid backup plan. He expected that Zucco would kill his henchmen, and so he had Robin take a picture of Zucco throwing a goon to his death. The Batman says they will send the film to governor, and that "'Boss' Zucco, your boss will be the 'electric chair'!"

Days later we see a newspaper boy announce that Zucco has been found guilty of murder and the governor intends to clean up city politics.

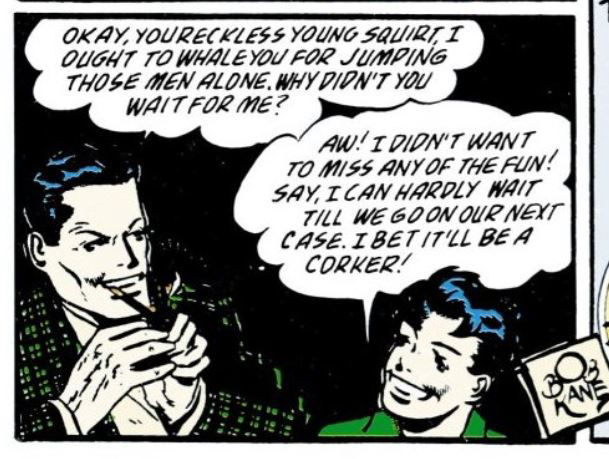

There's only one thing left to wrap up. Is the partnership of the Batman and Robin going to continue?

BRUCE: Well, Dick, now that your parents' deaths have been avenged, are you going back to circus life?

DICK: No, I think mother and dad would like me to go on fighting crime, - and as for me ... well .. I love adventure!

It may seem odd that Robin looks forward to the next adventure being a "corker" when this "adventure" was steeped in death -- including two very personal deaths.

Robin the Boy Wonder was avenging his parents’ murder, but still has a joie de vivre. Errol Flynn's Robin Hood also would swing between swearing to "exact a death for a death", but then share a hearty laugh as he larked about with Little John and Friar Tuck. That sense of humour mixed with darkness would in later decades become one of the Boy Wonder’s defining traits, although from the 1940s – 1960s, the tragic component of the mix was often downplayed.

Robin does follow a common Robin Hood trope by donning a disguise to get information. Batman has Dick do something similar in later issues too, investigating corrupt schools in Batman #3. But the disguise element is a common trope in adventure literature. Disguises occur in the tales of FulkFitzwarrin and Hereward the Wake, medieval outlaw figures that pre-date Robin Hood. And Sherlock Holmes employed disguises, but it would be a stretch to call him a Robin Hood figure. Most pertinently, Dick Tracy sent his adopted son Junior Tracy on similar assignments.

But the most explicitly Robin Hood element of the Boy Wonder’s origin in Detective Comics #38 (other than Robin’s name) is the Batman and Robin’s defiance of authority. Sure, Boss Zucco is a gangster – right down to the clichéd speech pattern of adding the word “See” after most sentences. But the Batman told Dick Grayson that Zucco controls the whole town, which appears to include the police. So, when the Batman and Robin step up their campaign against Zucco, it’s very much like Robin Hood taking on the Sheriff of Nottingham.

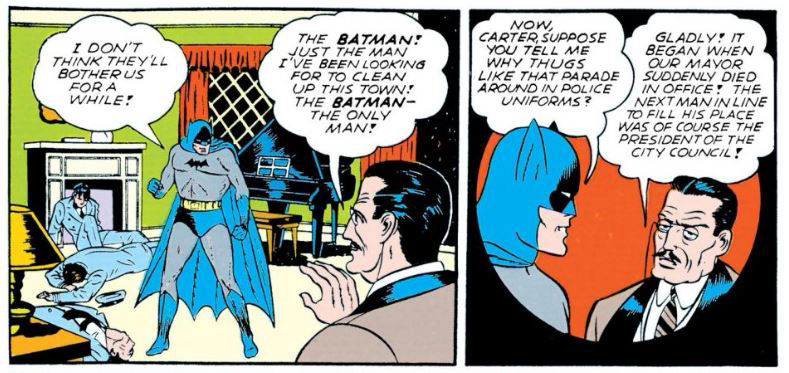

The Robin Hood-style action of Detective Comics #38 is repeated some months later in “The Case of the City of Terror” from Detective Comics #43 (cover dated September 1940).Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson are on a cross-country road trip when they arrive at yet another nameless city. The first thing the two visitors see is two cops harrasing someone who spoke out against the mayor. "I've got a right to say what I want! Free speech is ..." The police clubs him with his baton. "Free speech, eh? - You ain'tgonna be so free with it from now on!" The corrupt cop warns the crowd "And that's what happens to anybody else that talks against the mayor!" Bruce Wayne asks the townspeople don't report the policemen, but the folks don't answer, as they are too afraid that Mayor Greer has spies among them.

Dick says he has a feeling that they won't be having much of a vacation after all.

That night, Wayne changes into the Batman and goes to visit the home of Mr. Carter, "the most respected man in town. He's rich and has a lot of influence." The Batman finds a trio of cops are threatening Carter as he's "been shootin' your mouth off about the mayor!" "Yeah, that's libel!", says another cop as they prepare to drag Carter to jail. From the window, the Batman asks the police officers "Speaking of jail -- how long have you been out?" "Like an angry cyclone", the Batman knocks out the cops.

He then asks Carter to explain how "thugs like that parade around in police uniforms". Carter explains that the previous mayor had died in office, and so the position went to the next in line -- the president of the city council, Harliss Greer who Carter describes as "a crafty politician who took orders from our number one racketeer, 'Bugs' Norton!" Carter continues "Greer fired every honest official, he discharged all policemen and replaced them with 'Bugs' Norton's thugs!" The Batman asks why the people don't appeal to the governor, but that request needs to come from the mayor and local authorities -- who are corrupt.

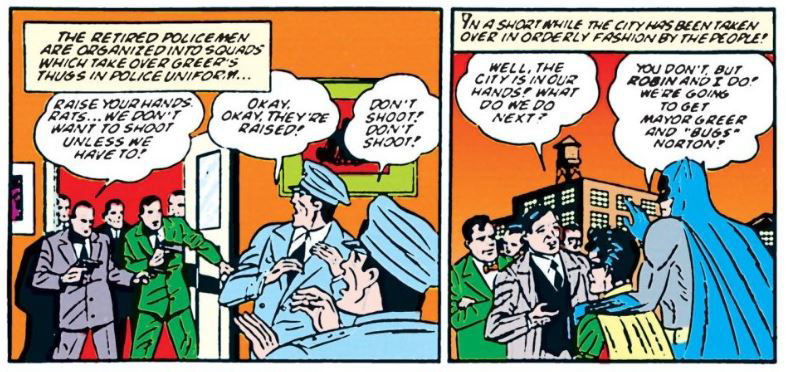

Corrupt, and not exactly legitimate. The current mayor may have been next in line for the position, but he wasn't directly elected mayor. And it's here that this Batman & Robin story intersects again with the Robin Hood legend in its 20th century form. The early Robin Hood references place the outlaw hero's adventures in different time periods. But the most familiar to us -- largely from its use in Sir Walter Scott's 1819 novel Ivanhoe is the time in the 1190s, when King Richard was away from England and control of Nottinghamshire lay in the hands of his brother, Prince John. In Robin Hood lore, Prince John is portrayed as a usurper and his power and that of the officials who report to him (such as the Sheriff) is depicted as illegitimate. Therefore, Robin Hood is only an outlaw towards illegitimate law makers. It's the law that has moved from truth and order, not Robin Hood. So too, Batman and Robin defy an unelected mayor and phony cops. As the Batman tells Carter, "If you can't beat them 'inside' the law, you must beat them 'outside' it -- and that's where I come in!"

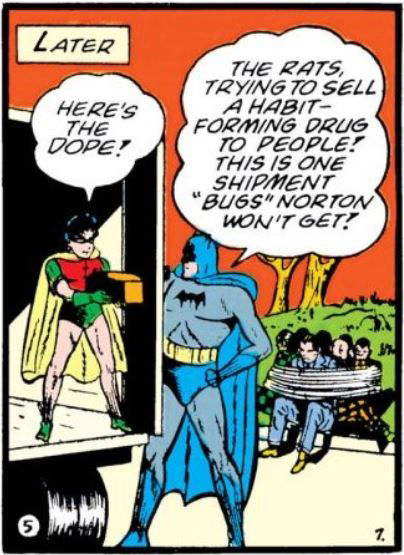

The Batman and Robin begin a campaign of intimidation which resembles the one in Detective Comics #38, including re-using the bat-in-a-box warning and smashing the bad guy's slot machines. The Dynamic Duo also breaks up a narcotics shipment. Then on his mentor's instructions, Robin rounds up some of the local kids with a printing press and encourages them to print and distribute leaflets of the "Tiny Press". All honest citizens are encouraged to meet at the Music Hall. The forcibly retired policemen take out their old service revolvers, and at Batman's encouragement organize themselves into squads and capture the thugs dressed as cops.

The common people take back their city, and then the caped crusaders capture Greer and Norton. With order restored, Bruce and Dick continue their road trip. Meanwhile, the grateful citizens unveil a statue of Batman and Robin.

Both Detective Comics #38 and #43 have stories where the Dynamic Duo take on gangsters and corruption with the promise of the restoration of order at the end. But there are some differences between the tales. Although there is a lot of fisticuffs in the latter story, there is nothing as violent as the death of the Flying Graysons or the Batman extracting a confession from a crook dangling on a noose.

That the citizens unveiled a statue of the Batman and Robin suggests our outlaw heroes were gaining a new respectability -- something that would play out over the next year in the comics.

It's notable that the Batman and Robin's most Robin Hood-like adventures did not take place in the heroes' regular city -- which would acquire the name Gotham City in Batman #4 (1940). The Batman does stop a corrupt member of Gotham's parole board in "Murder on Parole" (Batman #6, Aug/Sept 1941), but generally Gotham City is in honest hands. [This would change with Batman: Year One, the flashback tale by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchellithat ran in Batman #404 – 407 (cover dated February – May, 1987). This later story depicted the Gotham police force of the Batman’s early days as being rife with corruption, except for a heroic Lt. James Gordon, bucking against the system. The flashback ends with Gordon promoted to Captain – a step on his way to the more familiar role of Police Commissioner. Later retellings have followed Miller’s lead and depicted a more dystopian Gotham City. The industry governing code (introduced in 1954, but based in part on early house rules at DC) was under revision in the 1970s and 1980s – allowing for a less than rosy depiction of cops than had been possible in earlier decades.]

But back In the actual early years of the Batman and Robin, the cops were honest. Just not very bright.In Detective Comics #35 (January 1940), Commissioner Gordon is jealous of the Batman’s success and declares “That Batman. He’s done it again! He’s making the police department look ridiculous. I wish I could get my hands on him.”

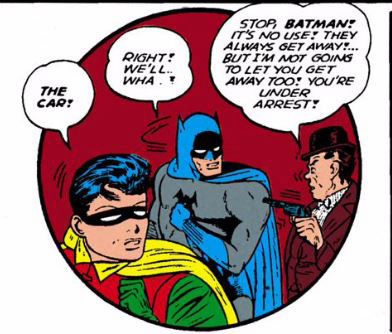

Actually, the person who would make the police look ridiculous is McGonigle, the dumb Irish cop who tried to capture the Batman and failed. McGonigle’s attempts were the most comic, but he wasn’t the only one after the Batman and Robin. For the first few years, the Dynamic Duo would often have to flee the police to avoid getting caught. Michael L. Fleisher compiled many of these early encounters with police in his The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes vol. 1, originally published in 1976 nd reprinted in 2007. Pages 110 – 114 feature “The Relationship with the Law-Enforcement Establishment”

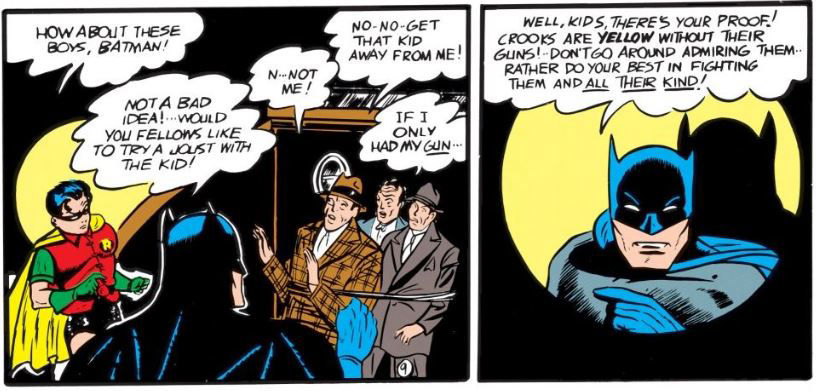

Batman and Robin may have technically been outlaws during this period, but at the same time the stories were already imposing strict moral messages that belied their outlaw status. For example, in Batman #1 (Spring 1940), Robin defeats a gang of thugs and they cower in terror from the Boy Wonder, muttering “If only I had my gun.” Batman turns and breaks the fourth wall by addressing the reader directly. “Well, kids, there’s your proof! Crooks are yellow without their guns! Don’t go around admiring them. Rather do your best in fighting them and all their kind!” Such moral statements were played in part for camp laughs in the 1960s Batman TV series.

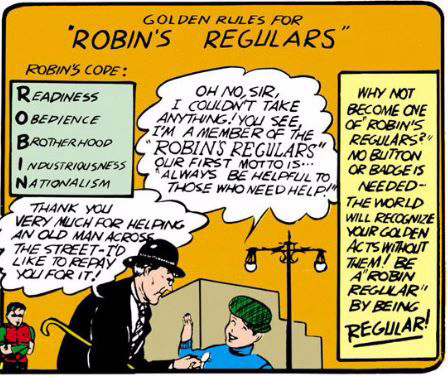

An even more Orwellian such message appears in the final panel for the issue when we are presented the rules for Robin’s Regulars. “Readiness, Obedience, Brotherhood, Industriousness, Nationalism. The caption requests that the reader “Be a ‘Robin Regular’, by being regular!” It begs the question just what is required to become irregular.

In Batman #2, when discussing a criminal’s short comings, Robin observes “United we stand, divided we fall.” And the Batman adds “Yes, Dick. A man who breaks away from the unity of law and order is bound to fall ... alone!” One issue later, the Batman slugs the clueless cop McGonigle to get away. Apparently that was not considered breaking away from the unity of law and order.

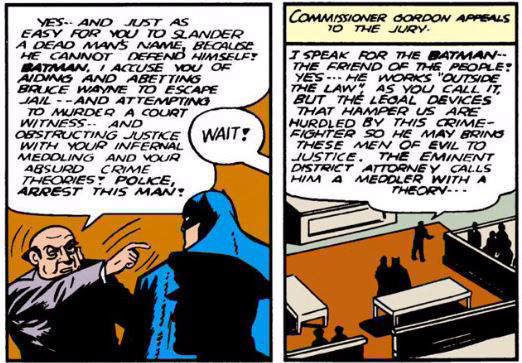

The Batman’s law and order platitudes were finally reconciled with his legal status in “The People vs. the Batman”, the final story in Batman #7 (Cover dated Oct./Nov. 1941). Bruce Wayne is framed for murder, escapes with Robin's help and the Batman solves the crime – beating the thugs into submission as usual. He then drags the mastermind behind the frame-up into the trial. However, the District Attorney won’t listen. One of the crooks had impersonated the Batman earlier in the issue. The DA turns on the Batman, accusing him of aiding and abetting Bruce Wayne, trying to murder a witness (the false Batman’s crime) and “obstructing justice with your infernal meddling and absurd crime theories! Police, arrest this man!”

But Police Commission Gordon has heard enough and intercedes.

I speak for the Batman, friend of the people! Yes -- he works "outside the law" as you call it, but the legal devices that hamper us are hurdled by this crime-fighter so he may bring these men of evil to justice.

This is one of those areas where adventure fiction contrasts with the real world. In the police movies of the 1980s we also see maverick cops in trouble with internal affairs for hurdling the legal devices. Audiences are sympathetic as these rebel heroes rough up the bad guys, ignore search warrants and the like. But would we really want that in the real world? What if the legal protections weren't hurdled to stop the Joker, but rather some social or racial groups that the cops were biased against?

It's a legal paradox that would remain in Batman comics for decades to come -- the police come to rely on Batman's clearly illegal methods. And yet with this 1941 issue, the comics give Batman legal sanction for his activities.

Gordon compares Batman to Washington, Lincoln, Edison, the Wright Brothers and so on. He lists the Batman's great achievements.

Gordon's summation would fundamentally change Batman and Robin's relationship with the police.

This man who daily risks his life to save others – who never carries a gun – who is aided by his young friend, Robin, fights crime with the courage and zeal born of love for his fellow man. This is …. the Batman.

Perhaps this comes a little late. but I, the police commissioner of Gotham City, appoint you an honorary member of the police department! From now on, you work hand in hand with the police!"

And with that handshake and declaration, the adventures of Batman (the definite article was soon dropped) and Robin were changed for decades. One could compare this to when Robin Hood was pardoned by the king (King Edward in the 15th century ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode and King Richard in the later tradition). But for films like the 1938 The Adventures of Robin Hood, the pardoning signals an end to Robin Hood’s heroic career. Order has been restored and there's no further need for a noble outlaw. In the ballad, Robin Hood grows bored with the inactivity of courtly life and turns his back on the king, returning to his outlaw ways.

It's likely that outside pressures led to Batman and Robin being made official allies of the law. On May 8, 1940 the Chicago Daily News published an article by Sterling North entitled "A National Disgrace!" Over the following months this article was re-published in several other publications and there were murmurs of how comic books were corrupting the youth of a nation.

National and All-American (the comics published under the DC banner) adopted editorial advisory board in 1941 - to help convince readers that their comics were wholesome and scrutinized by professionals. Having Batman shake the hands of cops rather than punching them was bound to make a good impression.

The early criticism of comics might seem familiar to Robin Hood scholars. Those who study the outlaw legend are well acquainted with people criticizing their tales. Here's one passage of Sterling North's 1940 article.

Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed -- a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems -- the effect of these pulp-paper nightmares is that of a violent stimulant. Their crude blacks and reds spoil the child’s natural sense of color; their hypodermic injection of sex and murder make the child impatient with better, though quieter, stories.

Police Captain Arnold, Batman and Robin in the 1943 movie serial

Robin in Star-Spangled Comics #65, 1947, art by Win Mortimer

Later comics would show that Batman had a special bat-shaped police badge. In the 1943 movie serial Batman, Batman (:Lewis Wilson) and Robin (Douglas Croft) are explicitly working for the FBI to stop foreign agents. However, Police Captain Arnold is jealous of the Caped Crusaders and tries to unmask them -- perhaps a nod to their earlier outlaw days

Robin's fame increased and he was given a solo spin-off feature in Star-Spangled Comics with issue 65 (February 1947) that lasted until that comic's cancellation with issue 130 in 1952.

But the Caped Crusaders' Robin Hood adventures weren't quite over.

As Batman and Robin's adventures moved away from real world crime, they started to acquire science fiction elements including time travel. And in 1946, Batman and Robin visited medieval Sherwood Forest and met Robin Hood. That tale is covered in our next section.

NEXT:

PART 4 - Batman and Robin meet Robin Hood in The Rescue of Robin Hood (Detective Comics #116)

PART 5: The Caped Crusaders in 1950s and 1960s Comic Books and Television

PART 6 - Batman and Robin Meet the Archer (1966 TV episodes)

PART 7 - Robin Leaves the Nest (1969 - 1975)

PART 8 - The Dynamite Duo and Goodbye, Hudson University (1975 - 1980)

PART 9 - Robin No More: The Birth of Nightwing (1980 - 1984)

PART 10 - Reboots and Retcons (1984 - Present)

PREVIOUSLY:

PART 1 - The Golden Age of Comics and the Development of the Kid Sidekick

PART 2 -What's In A Name? Robin and Robin Hood

Contact Us