The Batman editors wanted to ditch all the old tropes and schtick that dominated the 1960s TV show, including the kid sidekick.

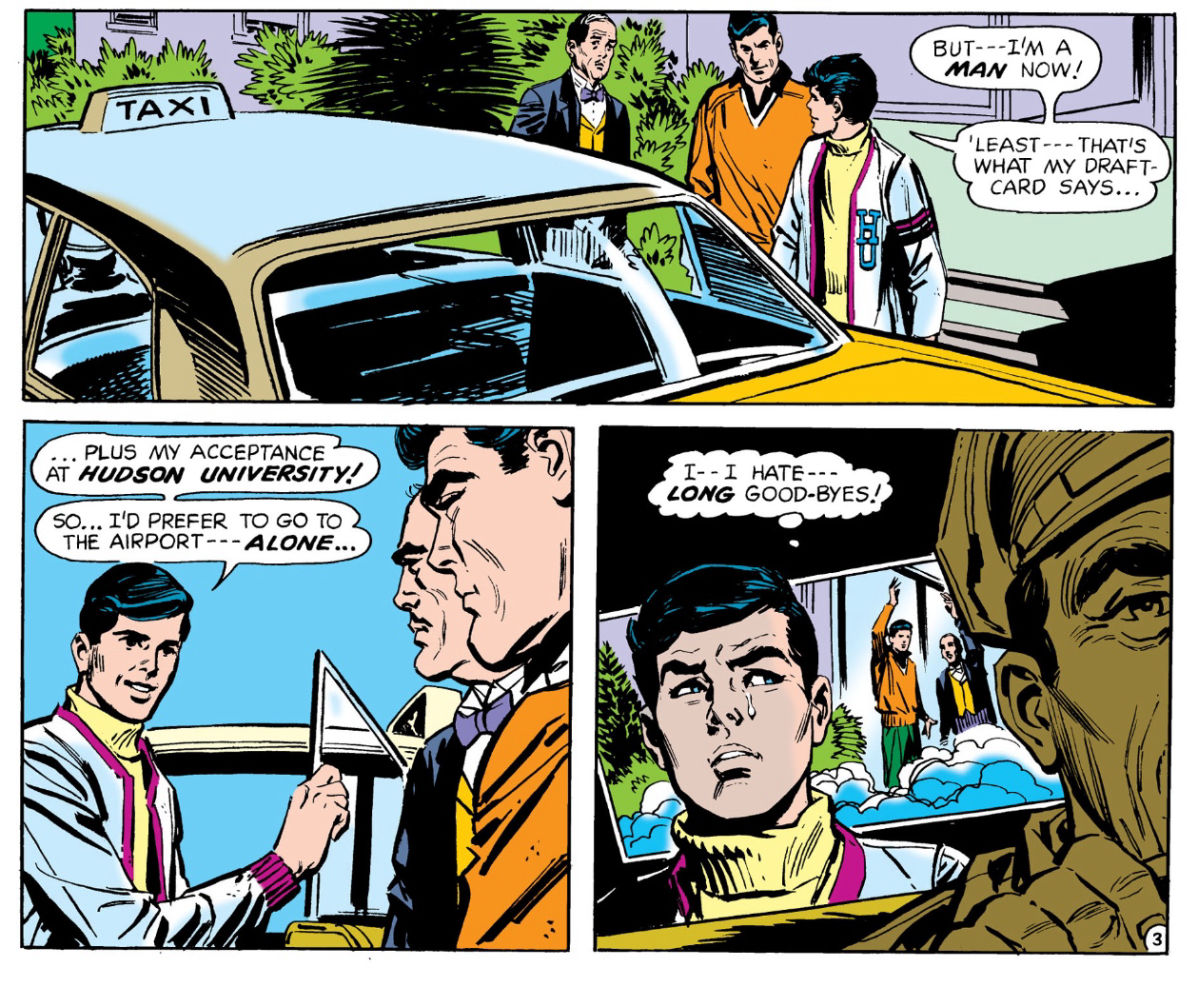

In "One Bullet Too Many" from Batman #217 (Cover date December 1969), writer Frank Robbins writes out Robin the Boy Wonder. Dick Grayson leaves Wayne Manor to head for the fictional Hudson University. (Later comics would establish that Hudson U. was located in the town of New Carthage in “Upstate Gotham”.)

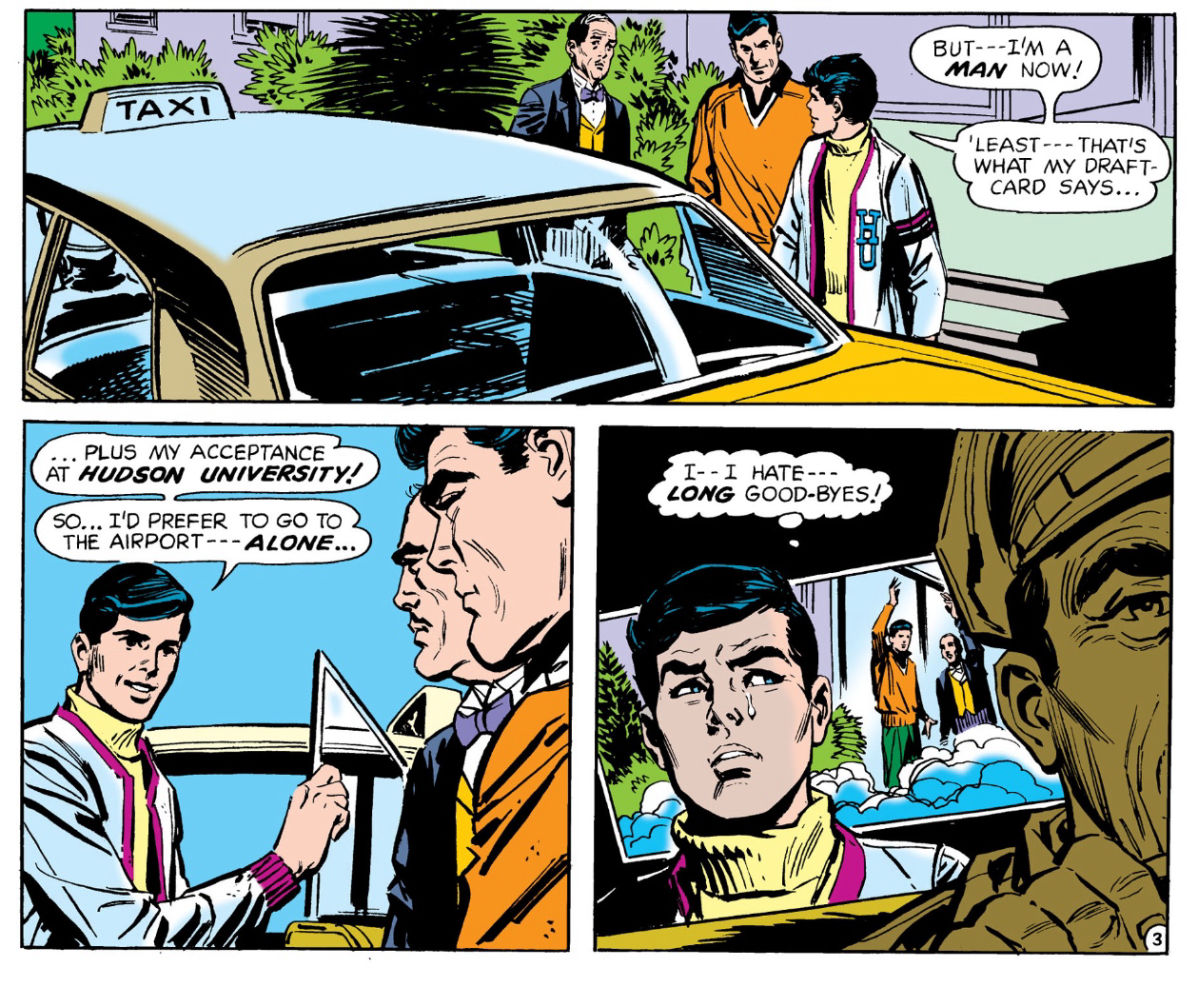

Batman -- or rather "the Batman" once again -- decides to make some changes himself. As Batman and Alfred glance around the Batcave, Batman says "we're in grave danger of becoming -- outmoded! Obsolete dodos of the mod world outside. Our best chance at survival is to -- close up shop here." Alfred wonders how the old crime-fighters will survive in the new world.

BATMAN: By becoming new -- streamlining the operation! By discarding the paraphernalia of the past... and functioning with the clothes on our backs ... the wits in our heads! By reestablishing the trademark of the "old" Batman -- to strike new fear into the new breed of gangsterism sweeping the world!

Today this new breed of rat -- uses the modern weapons of ... "phoney respectability" --- "big business fronts" -- "legal cover-ups" -- and hides in the fortress towers of Gotham's metropolis! We're moving out of this suburban sanctuary to live in the heart of that sprawling urban blight -- to dig them out where they live and fatten on the innocent!

Bruce Wayne and Alfred move to Gotham City and the penthouse atop the Wayne Foundation Building, home of Bruce's charitable organization. It's as if Robin Hood left the protected confines of Sherwood Forest to live in the heart of Nottingham. And yet, at this point the Batman seems more like Robin Hood than he had in decades. He's once again a defender of natural justice above the limits of the law. And as for the giving to the poor motif? Bruce Wayne uses the Wayne Foundation to fund the Victims Inc., Program (V.I.P.) -- to provide support for the victims of crime.

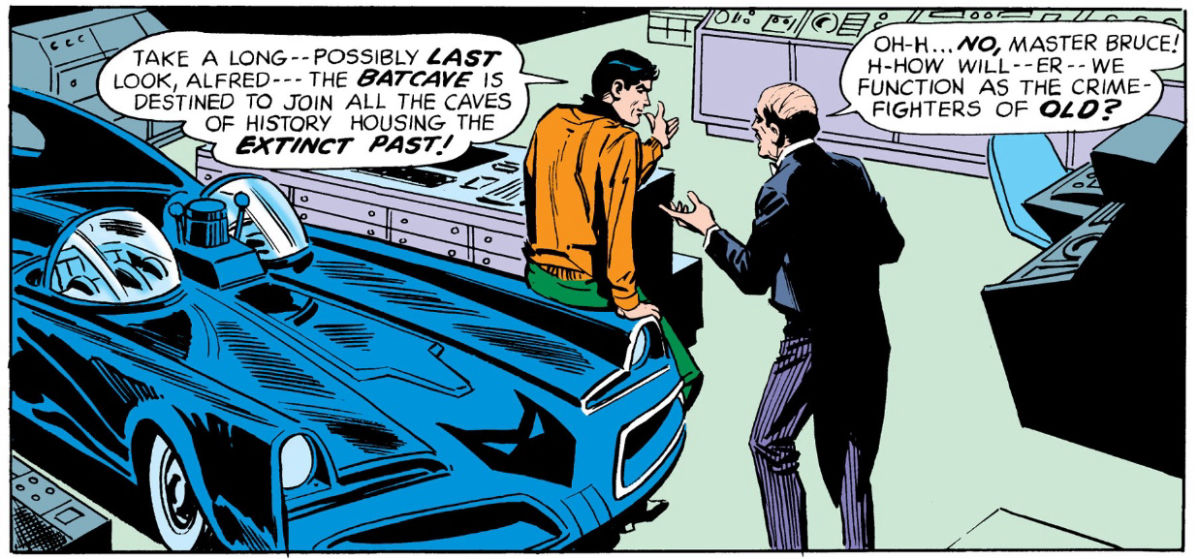

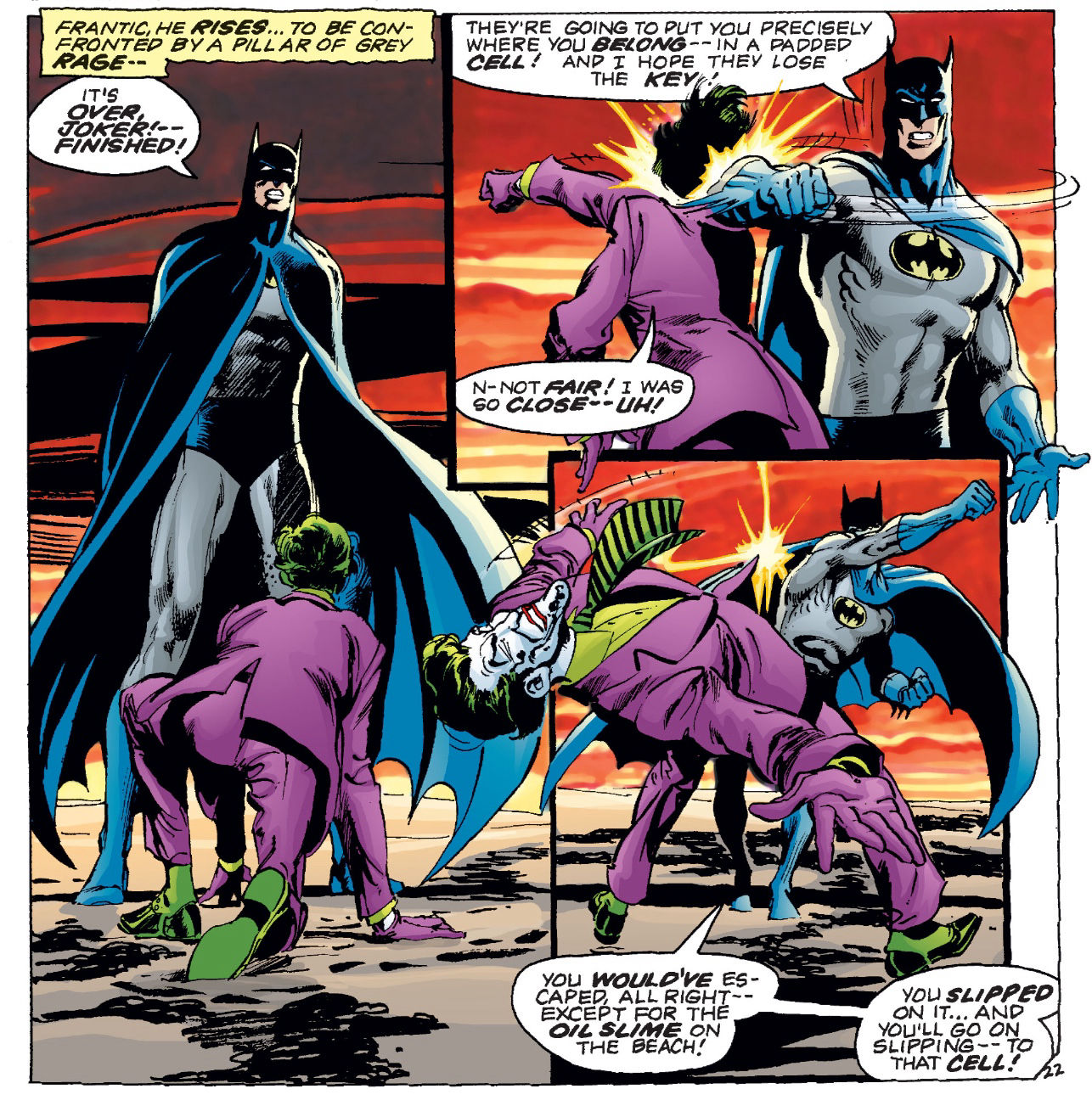

Some of the old tropes would return in time – the Batcave, Bat-gadgets, even the Boy Wonder. But the Batman was fundamentally changed as a character. So were his villains. When the Joker returned in Batman #251 (September 1973) by writer Denny O'Neil and artist Neal Adams, the criminal was no longer a prankster but had returned to being the psychotic murderer he had been in his earliest 1940 appearances.

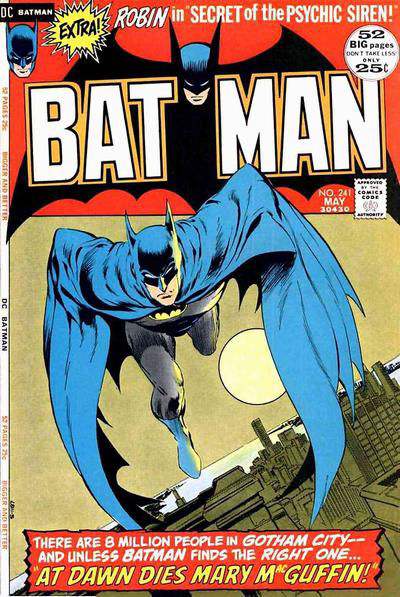

The Batman's new attitude was reflected in the way the character was drawn -- longer bat ears, more menacing shadows, and a longer cape that seemed to envelope one in darkness, not just a beach towel tied behind the back. The change began in 1968 when artist Neal Adams started illustrating The Brave and the Bold, the comic book series which teamed up Batman with various guest heroes. Adams’s style was popular and his design changes started to appear in the other Batman comics even before Robin’s departure for college.

The Robin Hood legend underwent a similar change during this time. Batman may have kept his tights, but Robin Hood didn't. The film Wolfshead (made in 1969, but not released until 1973) ditched the Sherwood Forest setting and the Sheriff of Nottingham for the Barnsdale setting of some of the early ballads and forgotten foes such as the Abbot of St. Mary's and Roger of Doncaster. Later productions such as the 1975 series The Legend of Robin Hood and the 1976 Robin and Marian might have restored the Sheriff and Sherwood Forest, but they kept the darker tone of Wolfshead. Robin Hood -- like Batman -- wasn't quite as safe any longer. Not that the general public noticed either change.

The Batman in the comic books - a darker figure without Robin. 1972, art by Neal Adams

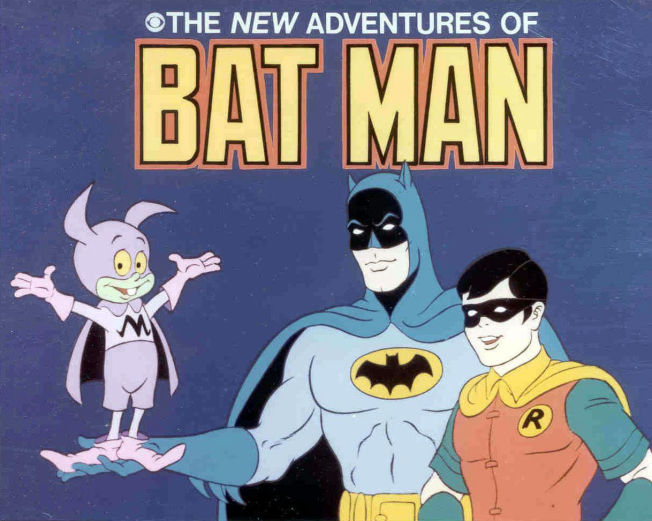

On Saturday morning, a brighter Batman with Robin in 1977's The New Adventures of Batman

Sean Connery in Robin and Marian, 1976 - one of the new look Robin Hoods in the movies

The friendly, hat-wearing Robin Hood of the ever-popular 1973 Disney cartoon

The traditional happy Robin Hood in tights was well-represented by the 1975 TV comedy When Things Were Rotten and the 1973 Disney cartoon. Meanwhile the general public best knew Batman through reruns of the 1960s TV series and the new cartoons Super Friends and The New Adventures of Batman (which largely seemed to follow the mid-1960s New Look period with elements of the early 1960s like Bat-Mite). If you were to look at Saturday morning TV in the 1970s, you'd find a Batman and Robin that were as inseparable as always.

But if the Batman of the comics was becoming more like Robin Hood, what about the character actually named for Robin Hood? What happened to Robin when he went to college?

Even before he left for Hudson University, Robin began appearing in occasional back-up features -- fighting wannabe Hell's Angels in Batman #202 (June 1968) and tackling bullies in Detective Comics #386 (April 1969). The Detective Comics' back-ups alternated with Batgirl features. In his last solo adventures as a high school student, Robin stops corrupt land deals that were prompting a teacher's strike (Detective Comics #390-391, August and Sept, 1969). These tales offer only a taste of the politics that would affect the next few years of Robin's adventures.

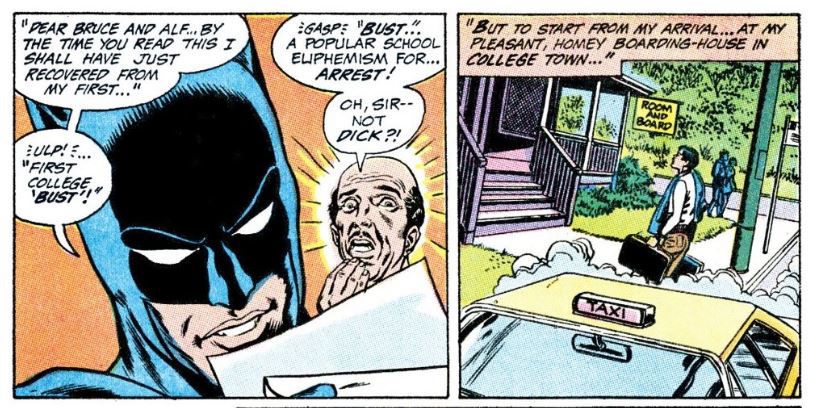

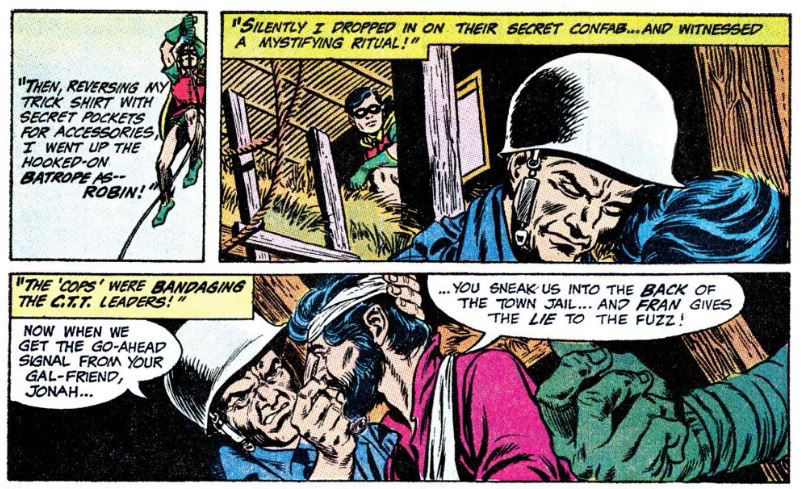

The first solo adventure with the college-student Robin came in Detective Comics #394-395 (cover dated Dec. 1969 and Jan. 1970) by writer Frank Robbins, with art by Gil Kane and Murphy Anderson. Dick Grayson had writes home to Bruce Wayne and Alfred the butler to explain how he had been involved in his first college bust. Alfred is shocked to hear that the straight-arrow Robin was in trouble with the law.

Dick explains how on his first day at Hudson University he ran into a student protest. The students are obnoxious and the campus officials beyond accommodating. The college dean shuts from his window "We have no intention of being provoked into violence on this campus! We will call no police -- now or ever! But we will meet or talk -- whenever you're ready!"

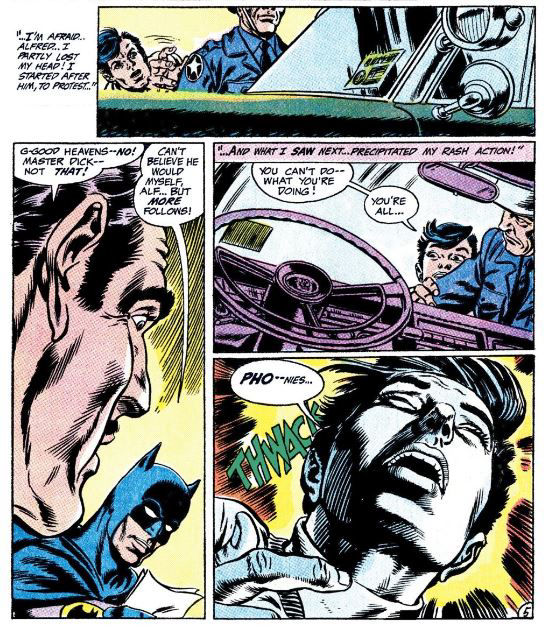

But the police do show up to rough up the long-haired radicals of CTT (Citizens Tomorrow -- Today). Or so it would appear. When he sees a woman shoved in the face, Dick is moved to protest the violent police action.

The young hero spots civilian vehicle registration stickers on the police cars and quickly deduces that the cops are phonies and is taken prisoner. He breaks free and changes into Robin. It turns out the fake cops are in cahoots with the radicals.

Robin jumps into action, punching the bad guys. But as the first part ends, the phony police are egging him on. The bad guys reveal in the concluding part that it benefits them if the protesters have bruises. Their plan is to turn the protesters into martyrs, sew distrust of authority, and create rebellion to shut the school down.

Why? One of the fake cops gloats "With America's universities closed, where do they get new brains to fight us, comrade?" Yes, the deceitful hippies are in league with the Soviets. Sadly the subject of police brutality is more relevant than ever in 2020, but the suggestion that it is all a lie created by foreign governments is deeply unsatisfying – to audiences now, and probably also to the contemporary audiences of 1969 who were involved in campus protests.

The Boy Wonder breaks free and exposes the scheme. Dick Grayson advises the campus "And don't take off on these misled 'leaders' -- their beefs may have been legit, but their tactics weren't!"

If that seems a little too pat and moralistic for the late 1960s and early 1970s, there's a reason for that. It's not that superheroes -- or Robin Hood, for that matter -- are inherently conservative. There have been left-wing and right-wing approaches to the characters. And it’s not just the age of writer Frank Robbins, who was born in 1917 and was 52 years old when the issues were published. Some of the other Robin solo stories of this period were written by Mike Friedrich who turned 20 in 1969, and those stories were also on the side of authority when it came to teen rebellion.

In 1969, comic book characters had to support authority. It was the first rule of the self-governing comics code instituted in 1954 which governed most mainstream comics. Section A.3 of the 1954 code states “Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.” If authority was to be depicted as unfailingly just, any protest would have to be deemed illegitimate.

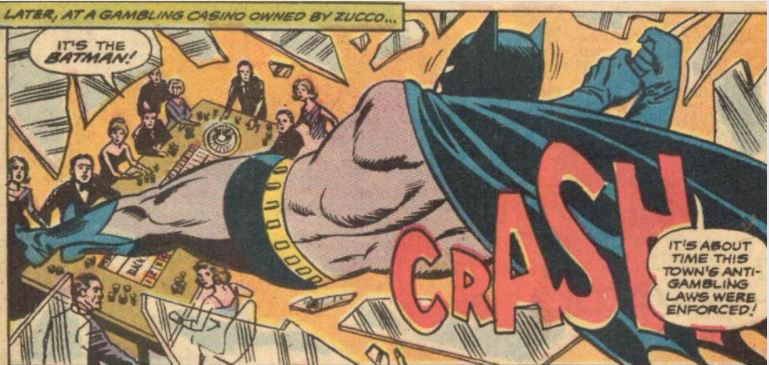

The code even affected the retelling of old tales. When Robin's origin was retold in Batman #213 (July 1969), there was a small but telling addition. Batman still busts up Boss Zucco's casino as in the 1940 original version, but now he adds "It's about time this town's anti-gambling laws were enforced!"

Batman was no longer a Robin Hood-like force for justice, but a force for law as well. The 1969 version also makes sure we know that Bruce Wayne went through the proper legal channels to become Dick Grayson's guardian, and had the consent of Dick's relatives.

Robin wasn’t the only superhero dealing with campus protests. Over at rival publisher Marvel Comics, Spider-Man encounters student protesters who want a campus building to be used for low-cost housing for needy students rather than accommodations for visiting –and much richer – alumni. Tensions come to a boil in The Amazing Spider-Man #68 (cover dated January 1969), and while the superhero’s sympathies are with the protesters, the police still take them into custody.

Two issues later the charges are dropped. It turns out the dean also planned to convert the dorm for low-cost student housing, but he didn’t disclose his plans while he argued with the university’s trustees. He apologizes for thinking his students should be seen and not heard. The Marvel approach is better. At least Marvel's young protesters are not fakers and communist dupes. But authority is still respected.

Eventually DC will take a more sophisticated approach to campus politics, and even the Comics Code would change in 1971 to allow for the depiction of corrupt authority as “an exceptional case and that the culprit pay the legal price.”

But before that, something else needed to change. The Boy Wonder was about to get re-branded.

Rpbin the Teen Wonder logo from Detective Comics #398

Robin as the Teen Wonder in Detective Comics #398, written by Frank Robbins, art by Gil Kane and Vince Colletta

Frank Robbins had Robin fight commies again in Detective Comics #398 and #399 (April and May, 1970), but there was small but immensely symbolic change.

Robin was no longer "the Boy Wonder". The back-up strip had been re-titled "Robin the Teen Wonder" starting with these issues. DC Comics would use the Teen Wonder nickname almost exclusively during the 1970s and early 1980s, just as writers insisted on putting a "the" before Batman's name.

For the young readers at the time, using the proper terms marked you as a real fan. Batman and the Boy Wonder were those campy characters from Saturday morning cartoons and the reruns of the 1966 TV show – as childish as adults thought they were. But The Batman and the Teen Wonder were more serious, more mature characters. Looking back with the hindsight of genuine adulthood, and in a world where there is such a thing as R-rated superhero movies and prestige HBO shows based on comic books, the slight distinctions in terminology may seem absurdly childish. But using the correct term "Teen Wonder" was a sign of allegiance to a then-disrespected artform, still struggling with newspaper articles that might claim comics were now more grown-up but still insisted in using the "Pow! Wham! Zap!" expressions from the 1960s TV shows. Fans of the Robin Hood legend might be able to relate to this insecurity when they recall the several newspaper articles which proclaim of each new Robin Hood film or TV show "this time, he isn't wearing tights".

Comics weren't the only medium that had endured a restrictive code. Films had been governed by the Production code for decades. But in the 1950s, films were beginning to rebel as the code. The Production Code’s standards were loosened. And by the late 1960s, the Production Code had been abandoned. Films like Bonnie and Clyde revelled in outlaw anti-heroes. Even Robin Hood was affected by this trend. The 1976 film Robin and Marian is in many ways an allegory for the Vietnam War, and the title characters perished in a murder/suicide. Movies were becoming daring, political -- relevant.

And the new young comics creators wanted the same freedom. DC Comics had hired new, young writers and artists -- partly to compete with rival Marvel Comics which was successfully engaging with 1960s counter-culture, but also to replace the old-guard writers and artists who were let go when they advocated for health benefits and better working conditions.

The comics this generation produced are often defined -- not without considerable derision -- by the word "relevance". Writer Denny O'Neil and artist Neal Adams led the way. Under their watch, the bland Batman wannabe Green Arrow was transformed into an angry, left-wing social activist hero. This modern-day Robin Hood led a fellow hero, the space policeman Green Lantern, in a road trip around America -- and the galaxy -- exploring issues like workers' rights, racism, pollution and overpopulation. Unlike the movie industry, the Comics Code remained in force. The superhero comics couldn't have quite the ambiguous ending of 1970s cinema. But they tried. In Green Lantern / Green Arrow #77, the heroes stop the corrupt boss of a mining town -- a clear victory to satisfy the code -- but Green Arrow wonders if conditions will actually approve. While they didn't feature former sidekick Robin all that often, O'Neil and Adams are also the most celebrated creators of Batman comics in the early 1970s. They infused the Batman stories with a sense of film noir, the darling genre for the makers of 1970s cinema. For a couple years, politics were all through the comics.

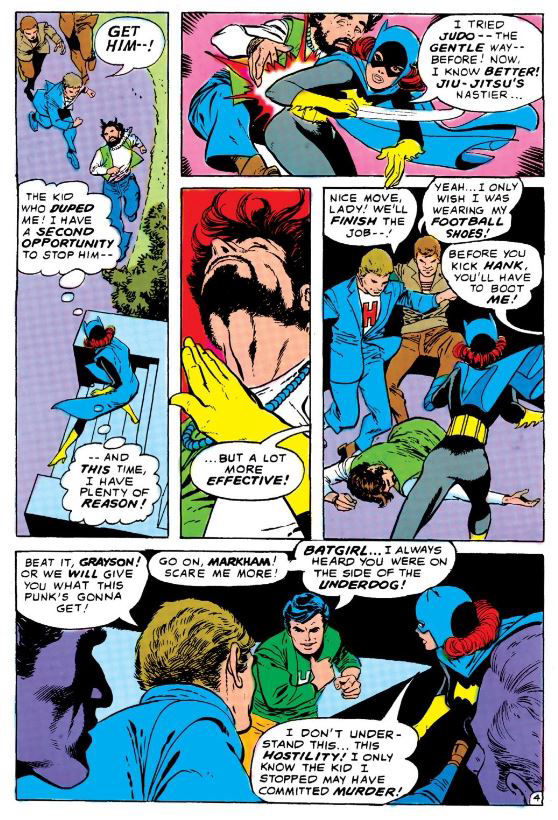

O'Neil did write Robin the Teen Wonder in a two-parter team-up/crossover with the other rotating back-up feature Batgirl in Detective Comics #400 and #401 (June and July 1970).

Batgirl’s alter ego of librarian Barbara Gordon had come to Hudson University to deliver a rare first edition for the campus' Edgar Allan Poe festival. (The story homages Poe and other mystery writers.) She hears screams from the campus library and when Batgirl investigates she runs into a long-haired campus radical fleeing the scene.

She discovers the college's murdered business manager, and then pursues the radical and knocks him unconscious. Some jock students, including a drama major, cheer Batgirl on and start kicking the radical. Dick Grayson interferes telling the jocks to back off, and he also castigates Batgirl. "Batgirl ... I always heard you were on the side of the underdog."

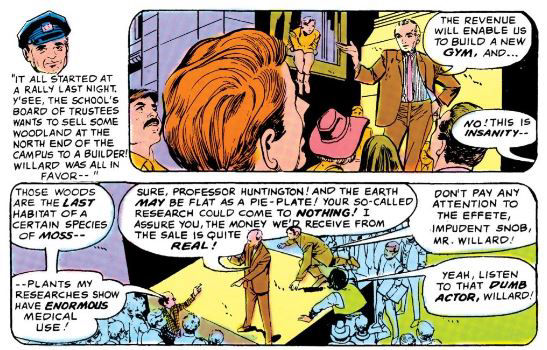

The murdered man, Amos Willard, supported selling off campus woodland for commercial development, a move opposed by the radical Hank Osher and a biology professor named Huntingdon (a possible nod to Robin Hood’s alternate name) -- and Dick Grayson. The jock-like drama student Jack Markham supports Willard’s money-making plans.

When Markham jeers the professor and Osher he borrows Vice President Spiro Agnew's infamous 1969 description of intellectuals as " an effete corps of impudent snobs.” O’Neil was able to sneak this one piece of anti-establishment dialogue past the Code’s censors. A year later O’Neil and artist Neal Adams would drawn the villains in a Green Lantern / Green Arrow story to resemble Agnew (but with a moustache) and President Nixon (disguised as a little girl in pigtails).

Knowing O’Neil’s politics, perhaps it isn’t surprising that the true murderer was Agnew-quoting drama student Markham. He committed the crime disguised as the radical, hoping to discredit the opposition.

It was the exact opposite of the set-up of Frank Robbins' story from six months earlier. This time, the campus radical was the innocent victim of a frame-up.

When Mike Friedrich resumed writing the Robin strip in Detective Comics #402, Robin took hastily action in breaking up a campus fight. The students gossip about Robin’s function. One student said "Reactionary vigilantes should not be allowed to operate in our society! Outlaw Robin!" The phrase reminds one of Robin Hood, and another student saw the Boy ... sorry, Teen .. Wonder as more the sheriff, in a good way. "Campus is a much safer place to be with an all-right guy like Robin to protect us from campus radicals! Robin for campus cop!" The two part story finished the following issue, and with that the Robin featured moved over to be the back-up in the Batman comic.

In Batman issues #227 and #229 (Dec. 1970 and Feb. 1971) we find Dick Grayson working on the congressional campaign of a left-wing professor Buck Stuart, who is challenging an incumbent who supporting the polluting big business ICM Corporation. A doctored photo makes it appear as if Stuart paid for pollution to be dumped in order to smear the incumbent congressman and the corporation. (The local newspaper is resistant to uncovering the truth, as its owner is allies with the incumbent and corporation.) Robin uncovers the truth and clears Professor Stuart's name and he goes on to win the election. However, during the course of the story Hank Osher -- the radical from the Batgirl team-up a few months earlier -- storms off believing it's not possible to achieve justice within the system.

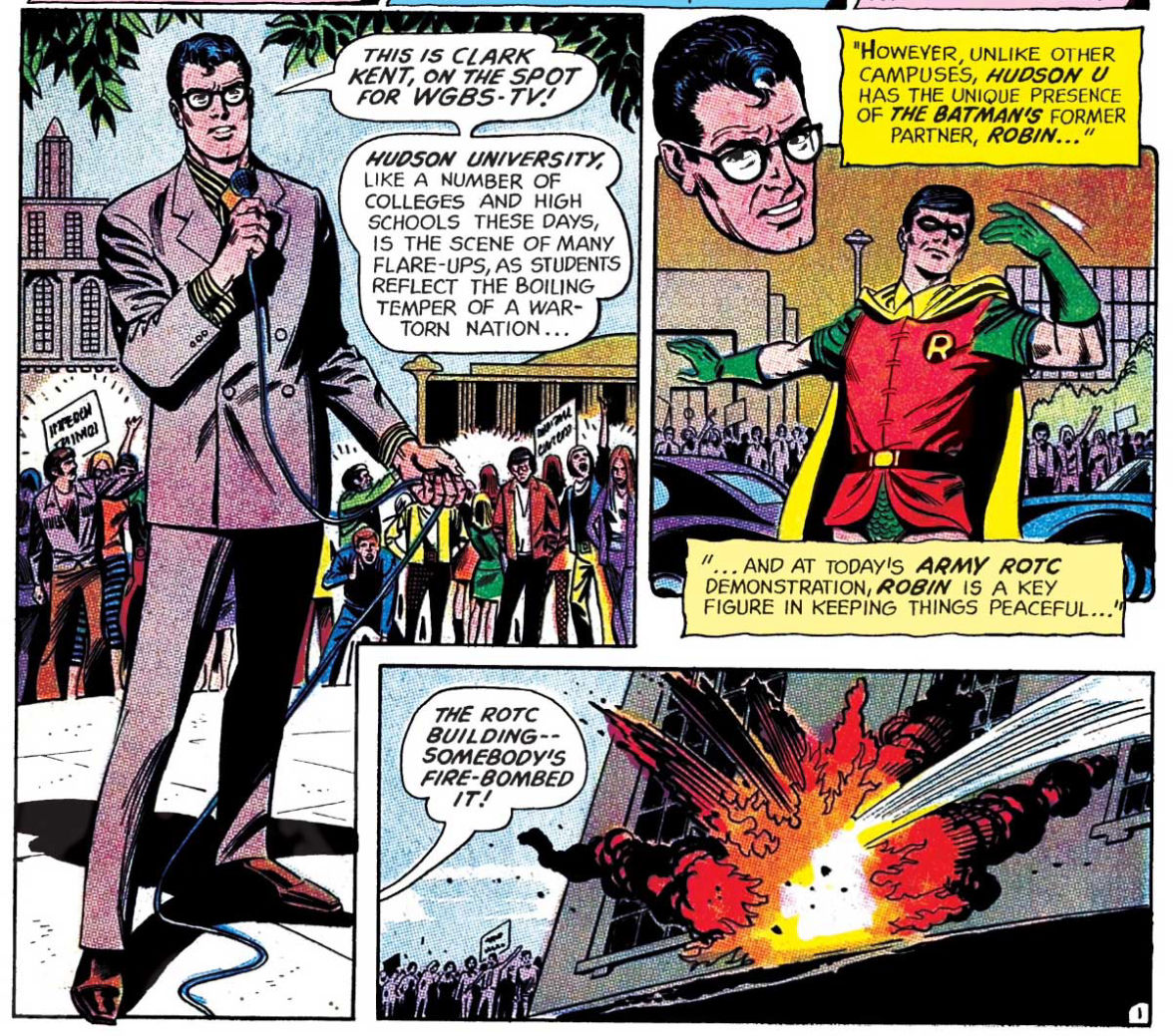

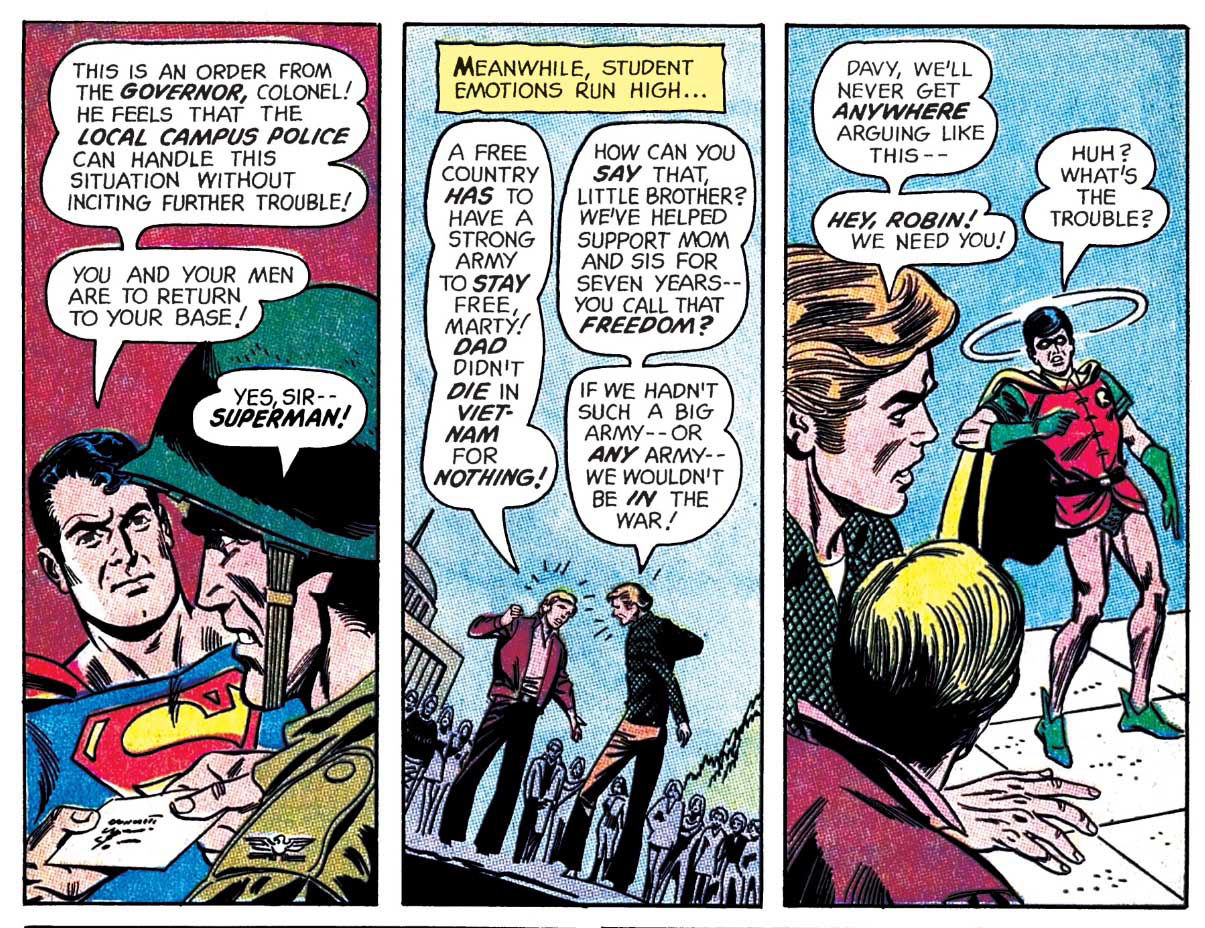

Robin's regular writer during this period also wrote a team-up adventure with Superman in World's Finest #200 (February 1971) that began students rioting on the Hudson University campus -- with the ROTC building firebombed.

Superman stopped the National Guard from committing a repeat of the Kent State Massacre. (Unlike the real-life events that inspired the scene, the Man of Steel had the governor's support to disperse the National Guard.) Meanwhile, Robin is asked to mediate a dispute over the American involvement in Vietnam.

Superman and Robin were transported to an alien world, along with two brothers -- sons of a soldier killed in Vietnam -- who used their off-world adventures to resolve their differences.

Friedrich continues the story in Batman #230 (March 1971) when a fight breaks out between the radicals and reactionaries on the Hudson University. Radical Hank Osher is revealed as the ROTC bomber, and is killed when explosives in his car go off prematurely.

In "Vengeance for a Cop" (Batman #234, August 1971), the politics of Hudson University intersect directly with the Teen Wonder's namesake, Robin Hood.

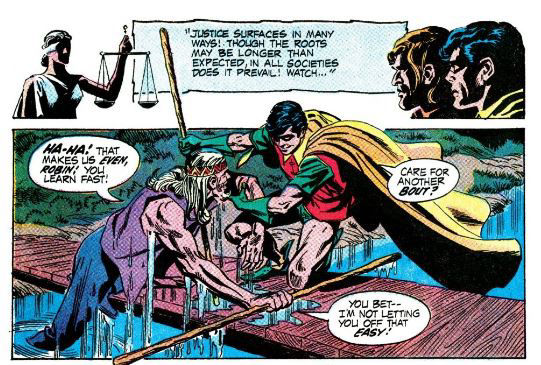

A campus police officer is shot, and Robin goes looking for his daughter who had run away to a hippie commune -- the Van Winkle, named for Washington Irving's story set in the Catskill Mountains of New York State. Robin meets the cop's daughter Nanci, her boyfriend Pat Whalon and a psychic classmate of Dick Grayson's Terri Bergstrom who had followed them To enter the commune, they must cross a stream -- along a bridge guarded by tall, long-haired commune leader Jonathan. He carries a quarterstaff and announces "Red-clad one -- if ye wish to join us, ye must best me with the staff!" Robin recognizes the parallels to the ballad Robin Hood and Little John.

Like his outlaw namesake, Robin loses the contest and is knocked into water. He acknowledges that Jonathan is the better man. The hippy leader responds "Those are the magic words, brother! You have shown the true requirement for welcome -- humility!"

As Robin is accepted into the hippie commune, he makes a deduction and accuses someone (we don't see who is pointing at until the next issue) of shooting Nanci's cop father and threatens to take the culprit to police headquarters. But Jonathan intervenes "I fear that is not possible, Robin! You're in a different world now! You can't grab him off unless we agree! And we say no!"

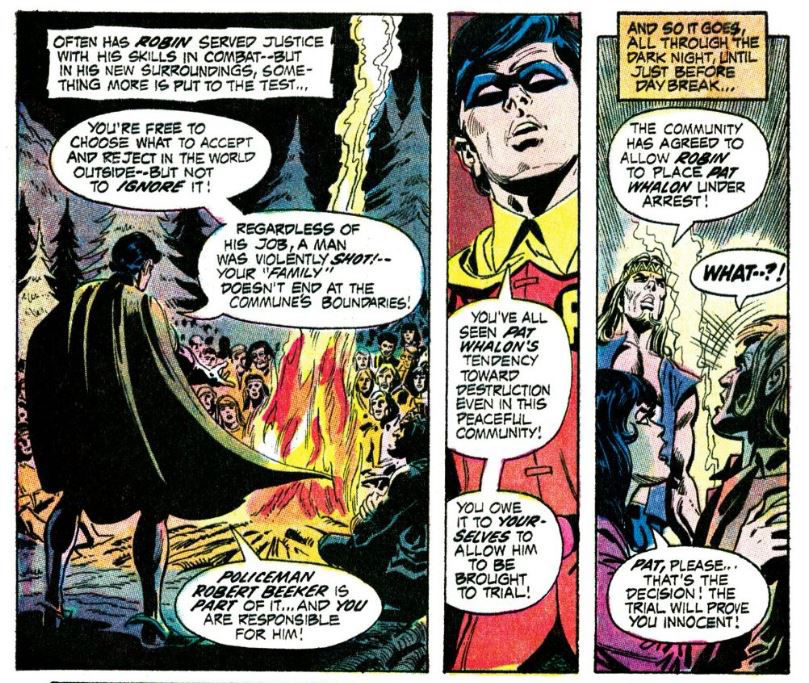

In the next issue "The Outcast Society" (Batman #235, September 1971) Robin tours the hippie commune -- seeing their ramshackle huts, the lack of running water (except that which they carry from the stream). The Teen Wonder can't understand why they'd live like that -- much like, although the text doesn't say it, the Merry Men. "You're almost totally isolated from civilization -- and what few neighbours you have completely distrust you! How can you give up so much -- for so little?" Jonathan rejects Robin's plastic society. "You're not in the same world! The rules are different here!"

Robin reveals it was Nanci's boyfriend -- Pat Whalon who had shot her policeman father. Nanci wears a bullet around her neck, a bullet removed from her boyfriend's leg and the same calibre of bullet that would have come from the cop's gun when he returned fire. The others remain unconvinced.

Meanwhile, Jonathan shows Robin around the commune -- comparing them to the pilgrims who had escaped persecution in Europe and which led to the American Revolution. "Our revolution is one of the soul!" Jonathan shows they have folk singers and explains the Little John-like quarterstaff duel from the previous issue. "There was even a purpose for your 'battling' me to enter the commune! We've recognized that we must have careful, ritual-traditions, without which our community can grow no roots."

Robin Hood's greenwood is, like the Van Winkle commune, an alternative society set apart from the rest of society. But the Teen Wonder argues that commune residents have a greater obligation to the world at large.

The commune agrees to let Robin arrest Pat Whalon and take him back to regular society for a proper trial. At this point, Whalon confesses and runs into the woods. He starts a fire which threatens to destroy the compound.

The next issue, Robin goes to a nearby town for help. The residents are skeptical and distrustful of the hippies, but many agree to help extinguish the fire. Eventually helicopters from the governor arrive and douse the blaze. Robin catches Pat Whalon, but the damage has been done. With the crops destroyed, Jonathan doubts they'll make it through the winter. One of the townspeople offers to help and thanks Jonathan for taking an early lead in fighting the fire. "Without you folks bein' so well organized, we'd all be have been in a peck o' trouble." Everyone, the Teen Wonder included, agree they've learned from their experiences.

The comic offers sympathy for the hippies, for the townspeople, and for the cops that work with honour. It might not allow for as much social criticism as would be permissible without a Comics Code enforcing conformity, but at least the alernative communities are treated with respect and understanding.

DC's archer superhero Green Arrow met Isaac, a hippie leader similar to Jonathan in Green Lantern / Green Arrow #89 (April 1972). Arrow called him "nature's Robin Hood" -- "steal from man ... give to nature!" But that was the final issue of that critically acclaimed run.

Julius Schwartz, editor of both the Green Lantern and Batman comics, took a look at the low sales figures for his political comics and decreed "relevance is dead!"

Friedrich's few remaining issues continued with the social elements of the 1970s "Jesus freaks", social acceptance and racism, but some transformed into an apolitical storyline to save Dick's psychic classmate a cult who worshipped the demon Cthulhu.

In late 1972, Friedrich's successor Elliot S! Maggin touched lightly on the political themes with Dick Grayson helping out disadvantaged kids but the political content had been toned down.

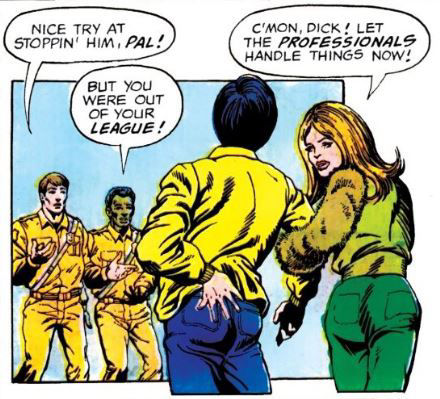

Lori Elton and Dick Grayson

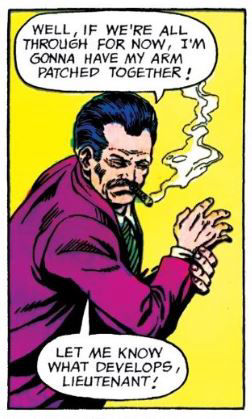

Chief Frank McDonald

By the time Bob Rozakis took over as writer in Detective Comics#445 (Feb/March 1975) the Teen Wonder was facing off such apolitical opponents against geriatric football players out for revenge.

Like Elliot S! Maggin before him, Rozakis was in his mid-twenties when he began writing Robin’s adventures – which were his first professional comic book stories for DC Comics, although he previously worked on their professional fanzine The Amazing World of DC Comics.

In his first issue, Rozakis added a new member to Robin’s supporting cast – Hudson University’s head of security Chief Frank McDonald, a moustache-wearing, cigar-chomping figure of authority. In Detective Comics #450, Rozakis created two more characters – Lori Elton, the reddish-blonde girlfriend of Dick Grayson (and niece of Chief McDonald) and New Carthage police officer Lt. Rick Tatem. These characters would follow Robin to his new home in the pages of comic book called Batman Family.

And in the stage of Robin's life, he'd once again have a bat-related partner, Batgirl, as part of "The Dynamite Duo".

NEXT:

PART 8 - The Dynamite Duo and Goodbye, Hudson University (1975 - 1980)

PART 9 - Robin No More: The Birth of Nightwing (1980 - 1984)

PART 10 - Reboots and Retcons (1984 - Present)

PREVIOUSLY:

PART 1 - The Golden Age of Comics and the Development of the Kid Sidekick

PART 2 -What's In A Name? Robin and Robin Hood

PART 3 - Early Adventures (including Robin's origin)

PART 4 - Batman and Robin meet Robin Hood in The Rescue of Robin Hood (Detective Comics #116)

PART 5: The Caped Crusaders in 1950s and 1960s Comic Books and Television

PART 6 - Batman and Robin Meet the Archer (1966 TV episodes)

Contact Us