Robin and Marian

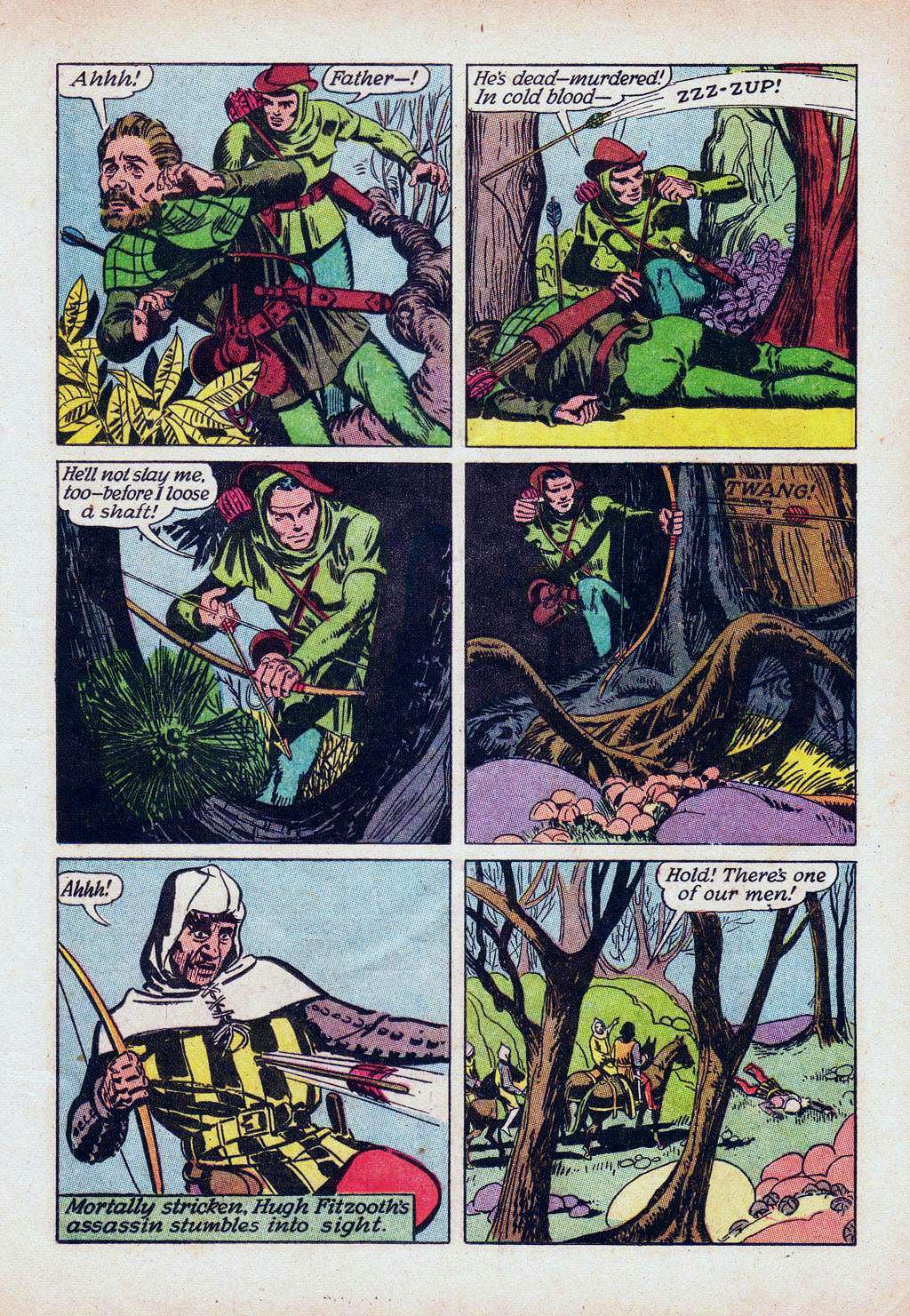

Richard Todd's Robin Hood feels very much like a prototype -- and likely inspiration -- for Richard Greene's Robin Hood in the 1955 TV series The Adventures of Robin Hood. Professor Stephen Knight has jokingly called Greene's Robin "Squadron Leader Robin Hood" and it seems an apt expression for Todd's outlaw leader too. It's an especially apt description for Todd who served as a lieutenant (later captain) in the British army and participated in Operation Tonga, part of the D-Day landings during World War II. His military experience would transfer to the screen in films such as The Dam Busters (1955) and The Longest Day (1962).

But while Todd's Robin Hood is an effective leader of the band, like Richard Greene's Robin to follow, this Robin Hood also possesses a rich sense of humour. We see flashes of the trickster in this Robin -- playful with his friends, and somewhat more sinister towards his foes.

Perhaps what brings out Robin's boyish side most strongly is his romance with Marian. We first see them as friends in happier days who play practical jokes on each other but with a deep love underneath. A criticism of adventure films is that the romantic attachments form too quickly. But in this case, the romance between Robin and Marian had been developing for years before we ever caught sight of them.

Joan RIce offers us a very different Maid Marian than the initially haughty Marian played Olivia de Havilland in 1938. Our first glimpse of this Marian is when she playfully moves Robin's target during his archery practice. This Marian is a bit of a trickster herself, with a tomboy-like quality. She takes matters into her own hands -- sneaking off to Sherwood to recruit her childhood friend/lover to the cause of raising King Richard's ransom. And whereas De Havilland's Marian needed to be won over to Robin's cause, Rice's Marian is a true believer from the start, only showing some doubt when she, Midge and Allan are robbed by Robin Hood.

Director Ken Annakin has some harsh words for Joan Rice in his autobiography. But if she was inexperienced on the set, it doesn't really show in the finished product. Rice's Marian is more lively than many who have played the role.