Introduction

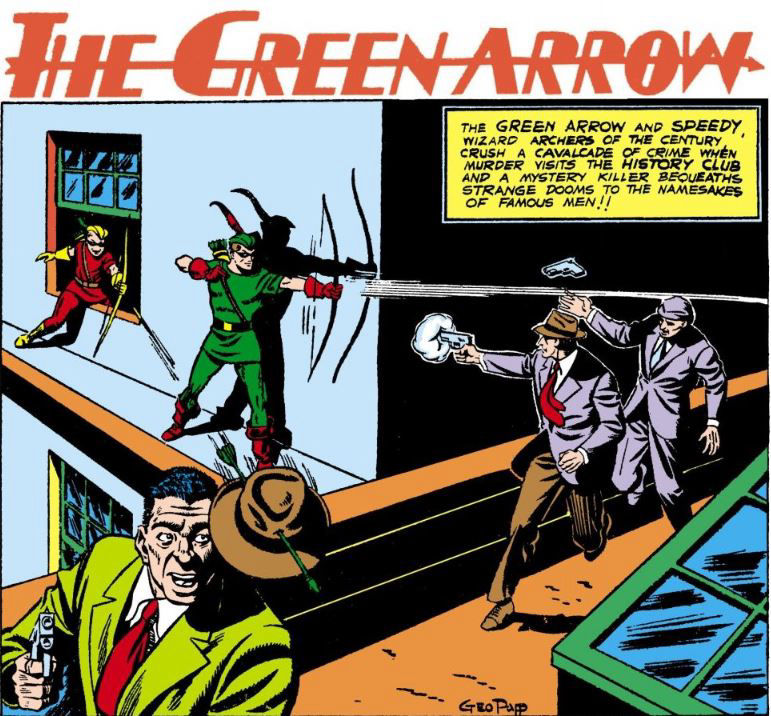

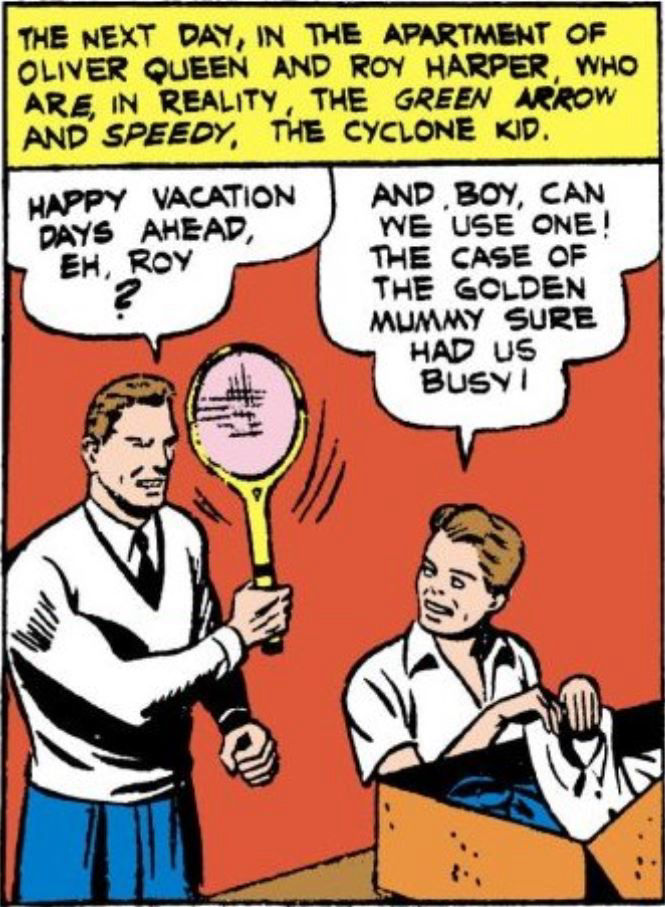

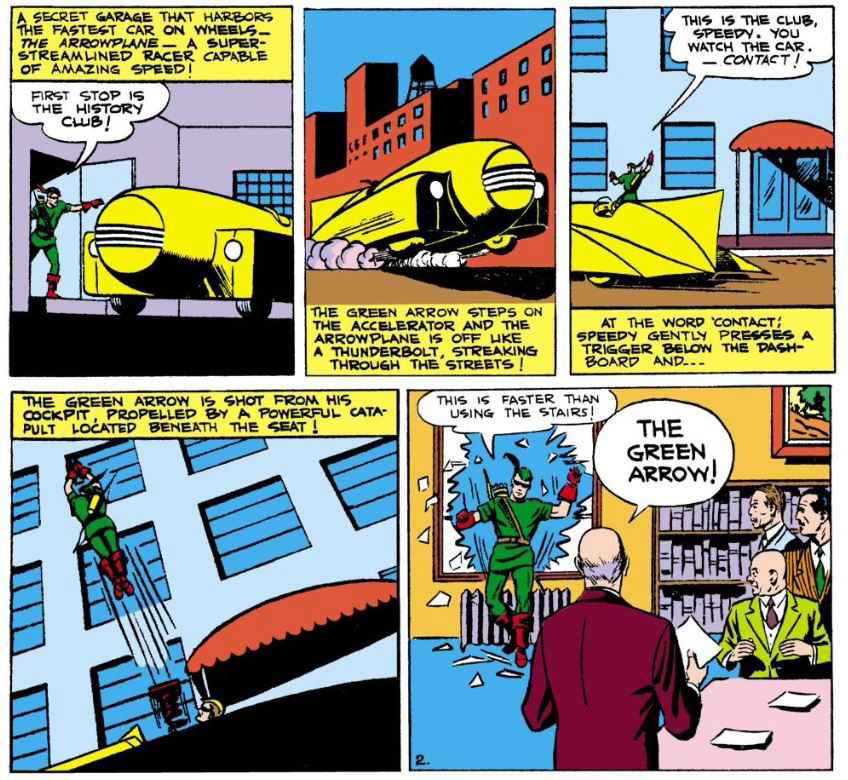

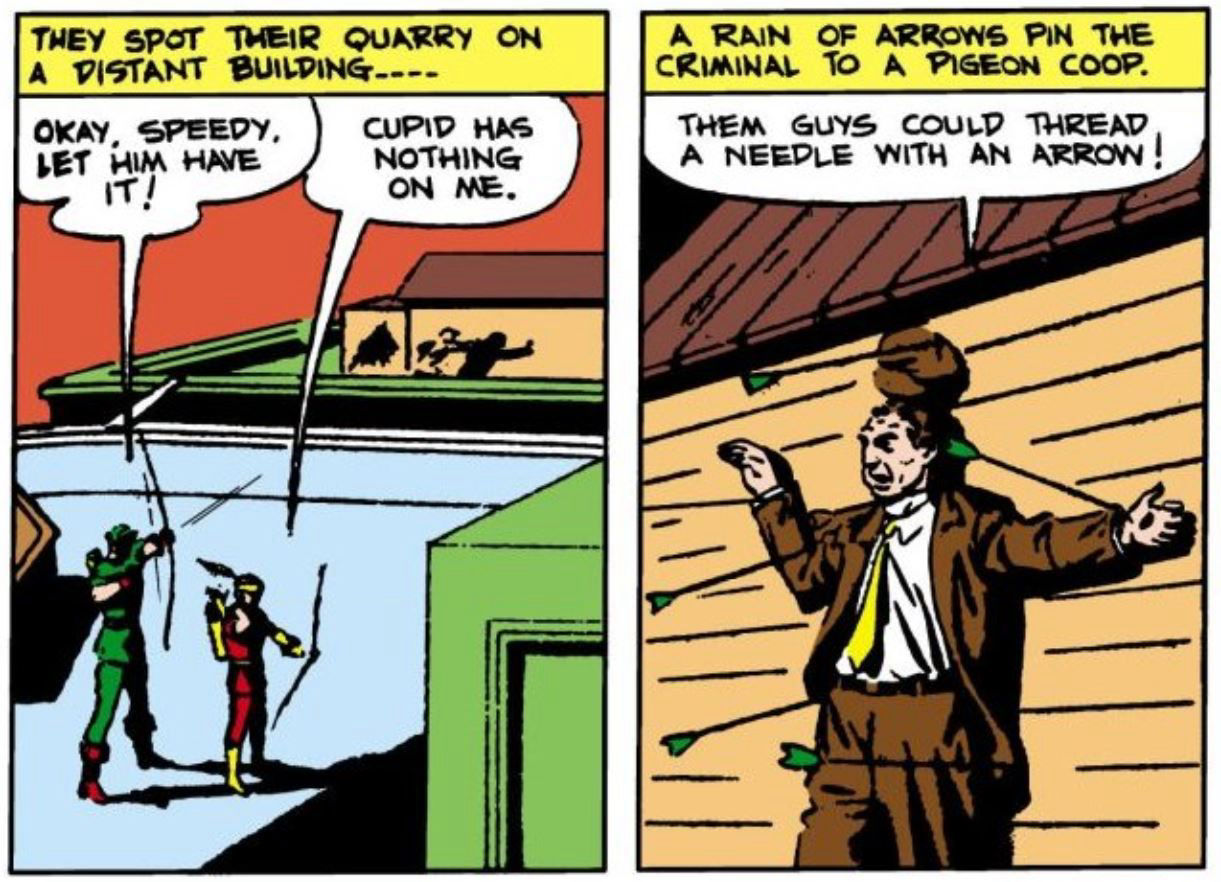

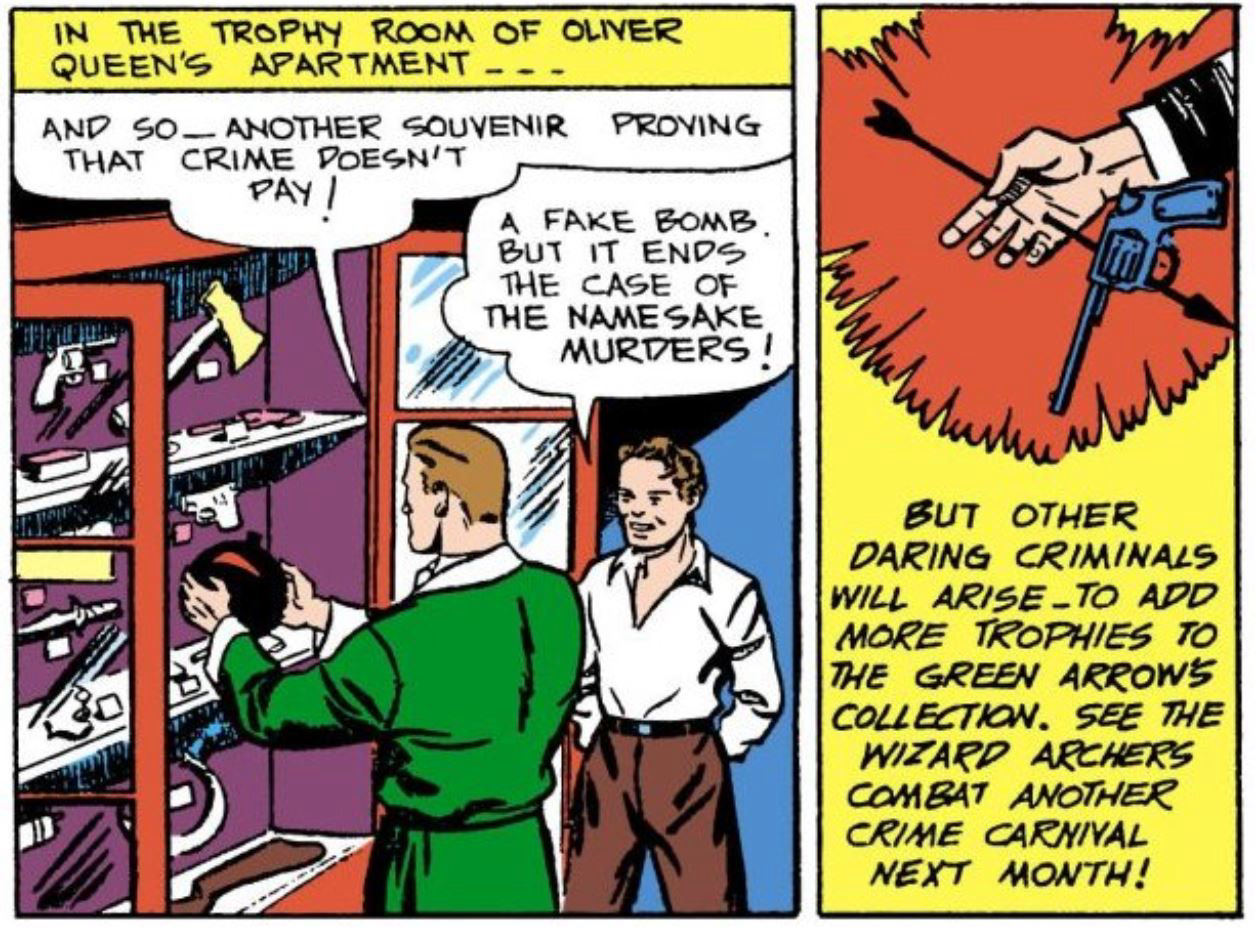

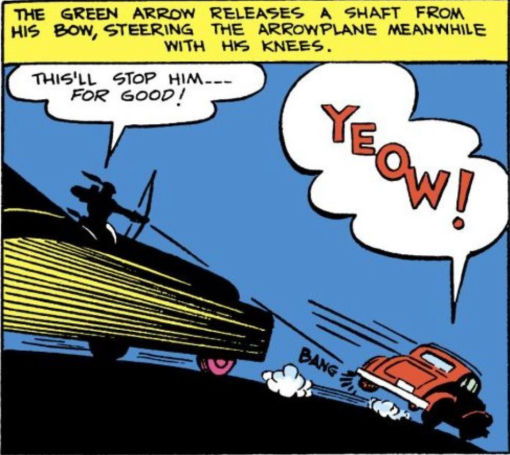

The Green Arrow was created by writer/editor Mort Weisinger and artist George Papp, and he first premiered in More Fun Comics #73. The comic had a cover date of November 1941, although it was likely on sale in late October. The only hint of a Green Arrow story on that comics cover was the declaration of :"Three New Features!" Aquaman was another one of those new features to debut that issue.

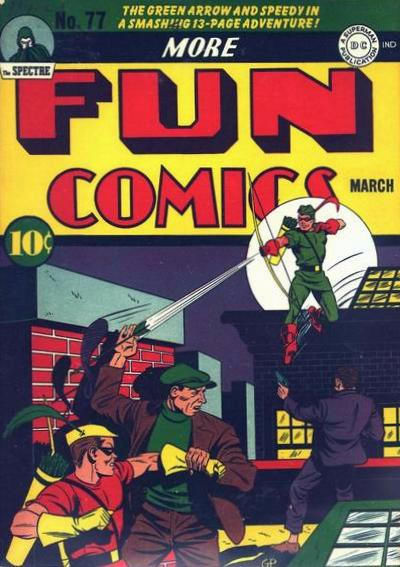

With issue 77 (March 1942), Green Arrow started appearing as the main cover feature. And Green Arrow stories would begin to appear in other comic books.

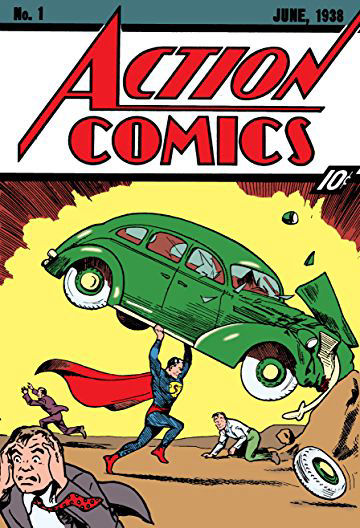

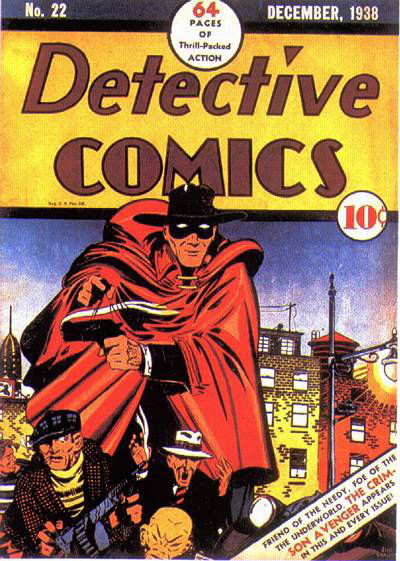

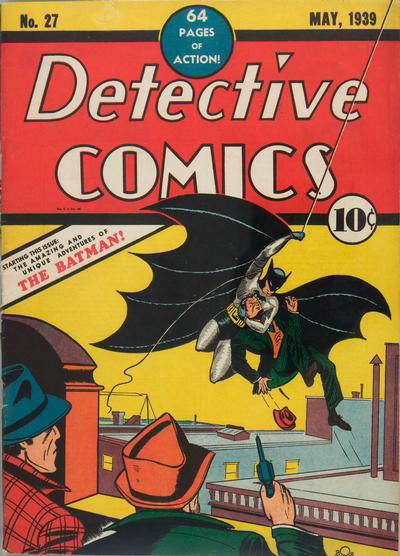

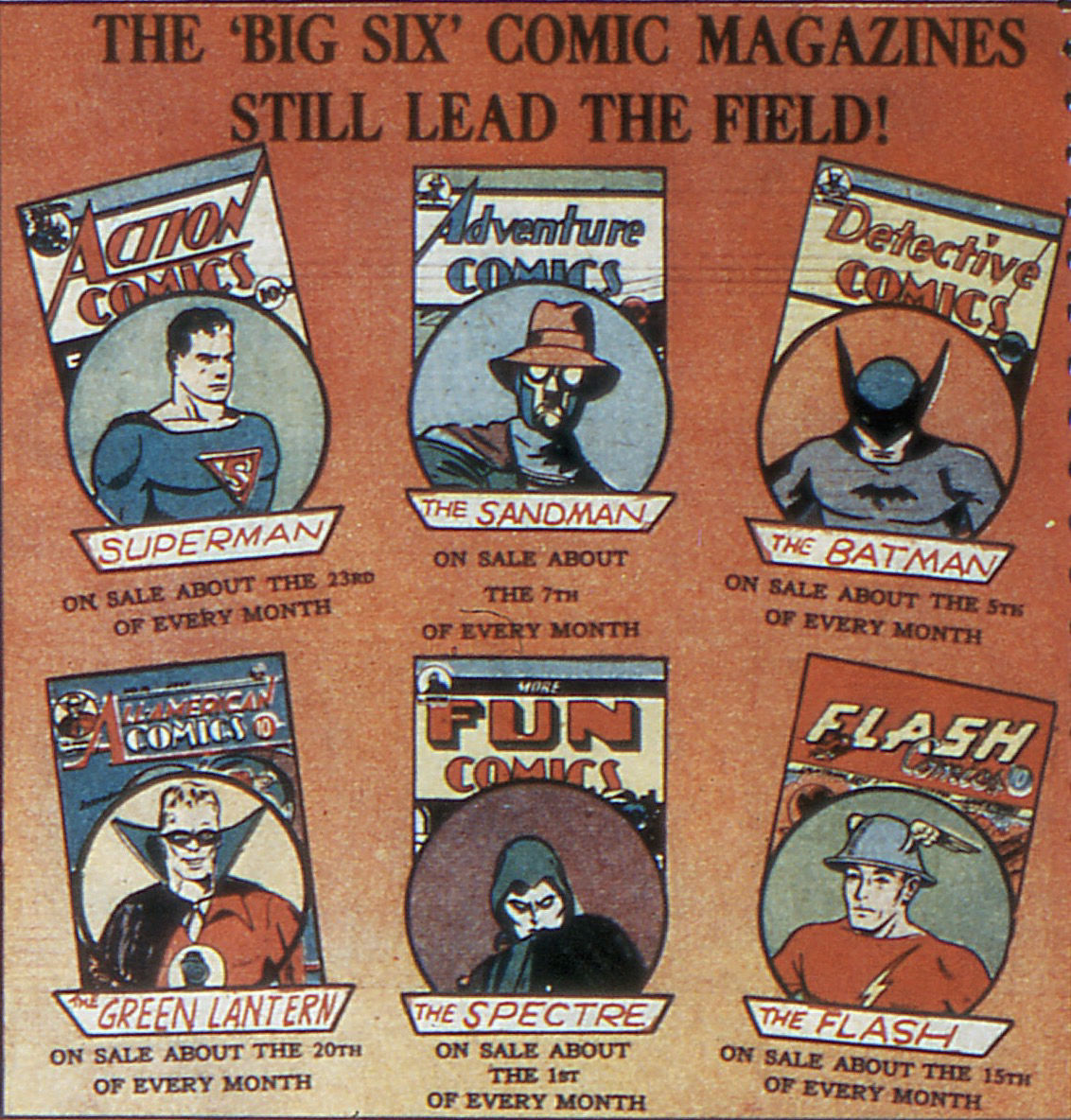

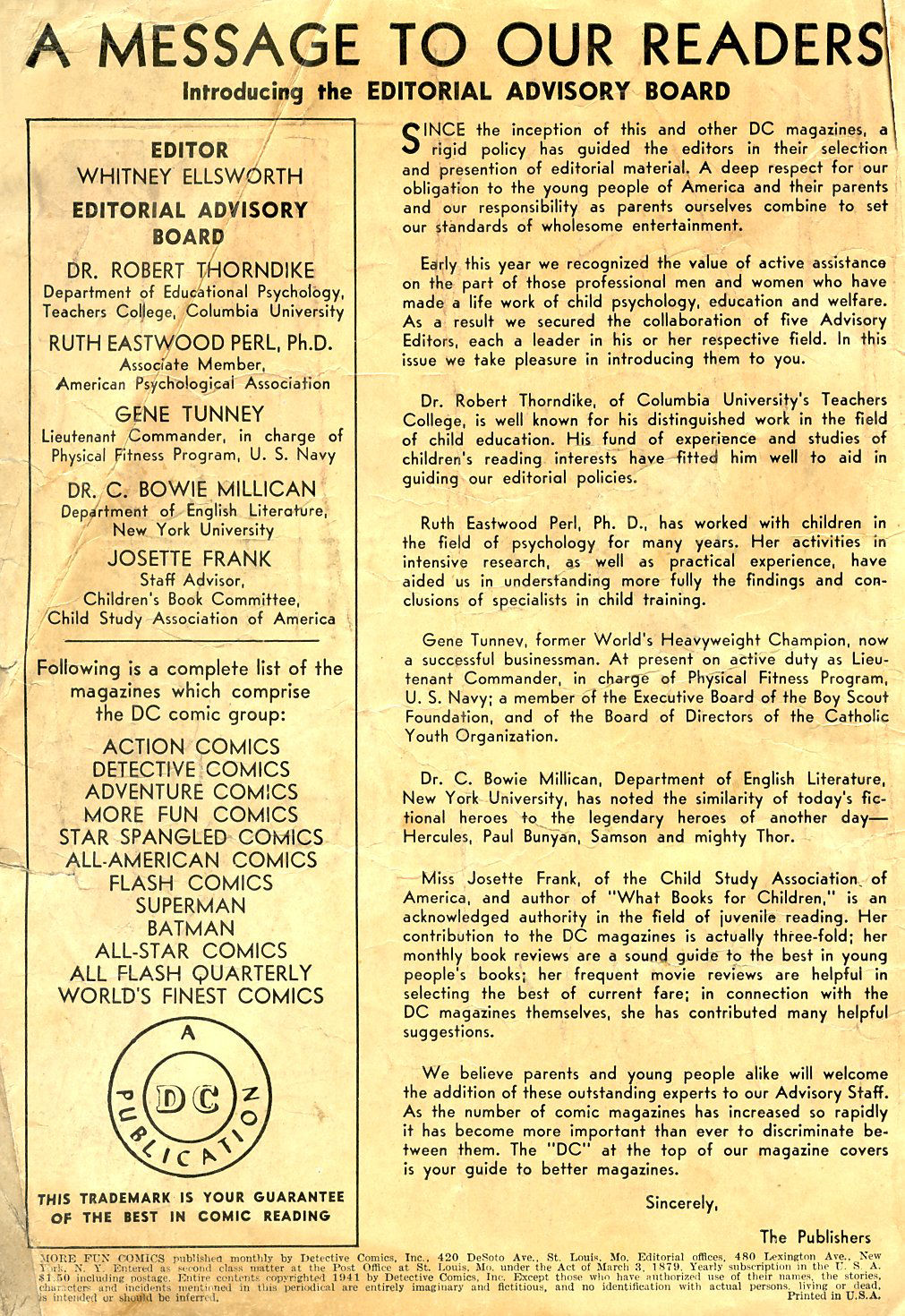

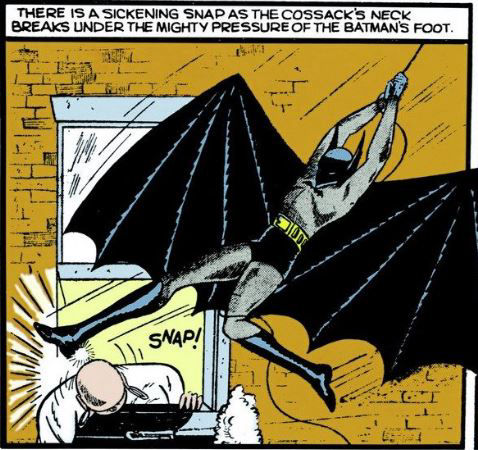

Green Arrow was more successful than many of the superheroes of his day but hardly top of the pack. It took Superman and Batman only a year to rise from their anthology comics Action Comics and Detective Comics to graduate into solo comics titled Superman and Batman. Green Arrow didn't get solo cover billing until 1983 -- 42 years after his debut.

So, Green Arrow wasn't an overnight success, but he kept on going when other superheroes had ceased publication.

This article looks at the early years of this modern-day Robin Hood.

Contact Us