Robyn Hood of the 1320s

For centuries chroniclers wrote about when Robin Hood lived. However, their dates conflicted each other, and we don't know the chroniclers' reasoning for picking various dates. As you'll read below, someone fabricated a family tree for Robin Hood. But in 1852, Joseph Hunter, a clergyman and assistant keeper of records, published a book offering proof of a real Robin Hood.

One of the earliest surviving ballads is A Gest of Robyn Hode. In the Gest, a "comely" king named Edward is travelling around the country. He meets Robin Hood, pardons him, and Robin goes to work in his court. Fifteen months later, Robin goes broke, gets bored, and returns to his outlaw life.

Edward II is said to have been handsome and extensively travelled England. Details of the king's progress in the Gest match a journey made by Edward II between April and November of 1323.

And Hunter discovered a Robyn Hood who served as a porter to the king's court between March 24 and November 22, 1324. In the last court entry, this Robyn was paid off because "he can no longer work". This historical Robyn was at the right place, the right time, and in the right sort of job for the Robin Hood of an important early ballad.

Hunter went on to speculate that this Robyn Hood was the same as Robert Hood, a tenant of Wakefield, Yorkshire who is mentioned in 1316-7. Wakefield is only 10 miles from Barnsdale, the medieval home of the legendary Robin Hood. And Robert's wife was named Matilda, Maid Marian's true name in two Elizabethan plays. A later writer discovered that Robert, like the legendary Robin Hood in some tales, may have been the son of a forester named Adam.

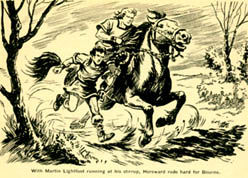

Hunter and others after him speculate that Robert Hood of Wakefield got involved in the rebellion against King Edward II that was led by Thomas of Lancaster in 1322, that Robin was outlawed, and later pardoned by the king when Edward visited Nottingham in November, 1323.

But there's no proof that Robert and Robyn were the same person, that either of them was a Lancasterian rebel, or that they were outlaws. And a record turned up showing Robyn was in the king's service on June 27, 1323, before the king's trip to Nottingham. J.C. Holt writes "this one reference destroys the coincidence of detail which made Hunter's argument seem so attractive." (p.50).

But these problems haven't stopped people believing in this Robin Hood. There are ways to explain the awkward dating. So this theory still has some fans. And even those who don't believe in it will acknowledge that a real Robin Hood might have come from Wakefield, where Hoods lived for centuries. Holt concluded "Either the Hoods of Wakefield gave Robin to the world, or they absorbed the tale of the outlaw into their family traditions or their neighbours and descendants came to associate the two. Of these the last is the most likely." (p.51)

Contact Us